ALBANY, Ore. (KOIN) — Madyson Jones jokingly refers to herself as a “frequent flyer” at her doctor’s office. But when she needs to make appointments, there’s hardly any waiting time or payment stress. She can just focus on getting well.

That’s because Dr. Matt Bain doesn’t accept insurance. Instead, he owns Mid-Valley Direct Primary Care in Albany. Patients pay a monthly fee and get unlimited office visits and access to regular primary care services like lab tests, immunizations, and imaging services for an additional cost.

“I’m able to spend more time and put more energy into my patient because I’m not having that sucked over to dealing with issues with insurance,” Bain said. “At the same time I can dramatically cut my costs.”

“I’ve had a couple emergency situations where I’ve needed to be in to a doctor ASAP,” Madyson said. “And he would get me in right then and there. Sometimes it was on a Saturday or a weekend. He would always make that effort to come and see me.”

Sometimes referred to as “cash-only doctors,” direct primary care (DPC) practitioners don’t accept any insurance, including Medicare or Medicaid. Bain, who has practiced in Albany for about 20 years, made the decision to transition to a fully DCP-practice about four years ago. The first couple of years were challenging — he described his financial security as “tenuous” — but he believed it would work and now it has paid off.

“It’s so freeing and I really look at it like I’m moving back in time to old-fashioned medicine,” he said. “The patient is in charge of what we do.”

Madyson started seeing Dr. Bain when she was in high school and not aware of the intricacies of the insurance process. But her father, Jerry Jones, remembers it well.

“Costs just continued to rise,” Jerry said. So his family started looking for other options. They settled on joining a health care sharing ministry to cover any catastrophic incidents, and go to Bain for routine care. A self-employed realtor, Jerry estimates his family saves about $1,200 a month from what they were paying before. But the real benefit, he said, is the peace of mind of having a close relationship with his doctor.

“Direct primary care is certainly not insurance”

About 25 miles north, in Salem, Dr. Manya Helman has been running what she would call an “insurance-free practice” since the late 1990s (though she only adopted the term “direct primary care” recently). She has about 270 patients at her practice Wellness and Recovery of Salem and thinks she could handle a maximum of 400 without having to sacrifice service.

One patient, Tracey Zwemke, said it can take up to two weeks to see her insurance-based doctor, but with Helman, sometimes she can call and get in the very same day. She has an unlimited number of office visits, so she comes in as soon as she’s feeling unwell, rather than putting it off until it becomes more serious.

“I don’t sit in a waiting room for hours,” said Terry Wyatt, a patient of 16 years. “I get in, get out, and they handle everything I need, taken care of right here.”

Wyatt said, as a small business owner, traditional insurance “hasn’t been in the cards” for him so far. However, both doctors Bain and Helman stress that DPC does not cover everything.

“Direct primary care is certainly not insurance,” Helman said. “They need insurance for anything they can’t afford out of pocket.”

Think brain tumor, heart attack, leukemia, or other serious illnesses or injuries.

“(DPC) dovetails beautifully with any high deductible plan, which of course is going to be less expensive,” she said.

Why isn’t it more expensive?

“You hear all the time how expensive healthcare is,” Bain said. “It’s not true at all. What’s expensive is the third party administration of healthcare. That’s catastrophically expensive.”

Bain said when you pay for insurance, you’re paying overhead, personnel, advertising and other costs for a huge corporation.

“So you’re going through several steps where your money is getting siphoned out before you get to the care,” he said. That adds up to what may seem like astronomical costs for a simple office visit.

Helman added that society has come to believe that if something isn’t covered by their insurance — or is too expensive under their plan — then they can’t access it.

“It’s not insurance at that point,” she said. “It’s prepaid care.”

Bain said he is also able to cut out steps that might normally be required by insurance companies. For example, if a patient comes in with a knee problem, their insurance might require a certain number of physical therapy visits before they are allowed to get an MRI. Dr. Bain, on the other hand, will just let his patients get an x-ray or MRI if it looks like that’s the best option. Contracting with insurance and Medicare wouldn’t necessarily allow that.

Accepting Medicare also opens doctors up to fraud allegations, even if they’re trying to do the right thing, like waive a copay or give a patient a cheaper treatment option, according to Helman. An example she gave would be treating pink eye. Medicare might ask a doctor to give the visit a code as either viral or bacterial. But she said her practice doesn’t culture to find out which kind of pink eye it is, they just treat it.

“I’d be in the position of having to say something that wasn’t true, for a $35 visit,” Helman said. “There’s paperwork and law and government and then there’s reality. In the end with all the fuss about insurance and health insurance, people were left without adequate care.”

Bain and Helman both work with local radiologists and other specialized service providers to get a market discount. Bain said his patients normally pay 15% of the normal cost. In other words, if an MRI would usually cost about $600, his patients might pay closer to $90.

There isn’t really a DPC option for surgery in Oregon, according to Bain and Helman. Some patients have gone all the way to the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, which has made headlines with its price transparency.

DPC gets a nod from D.C.

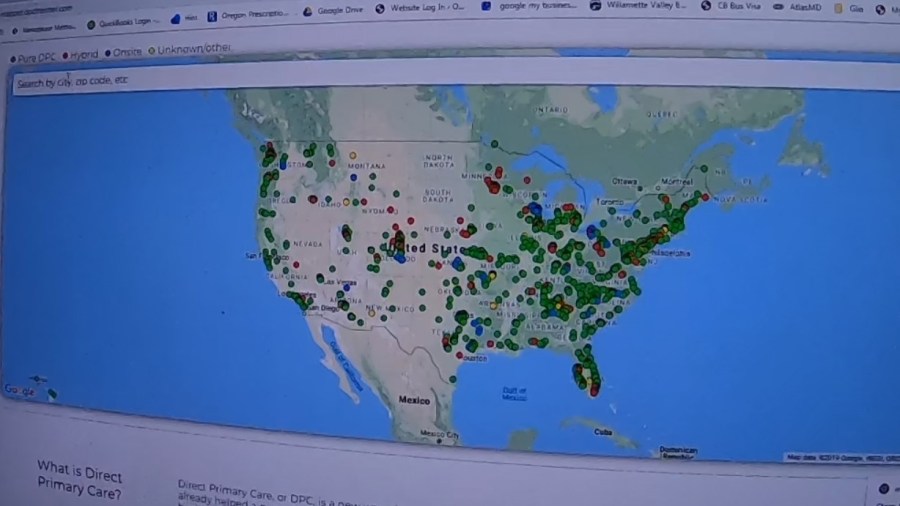

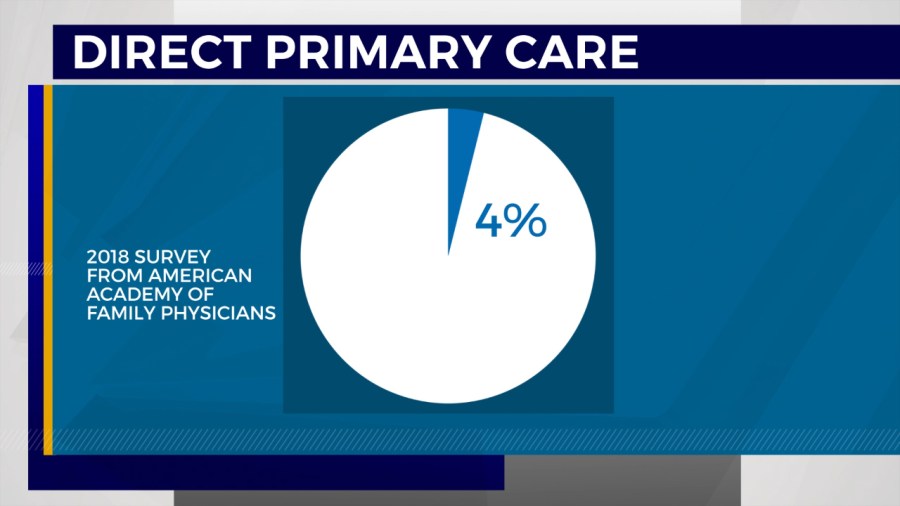

According to a 2018 American Academy of Family Physicians survey, only about 4% of physicians are working in a DPC setting, with a smaller number actively working to become a DPC. The survey also showed the familiarity with the practice has risen over the past several years.

The federal government is taking notice, too. Right now, DPC patients cannot use a health savings account to pay for services. Democratic Representative Earl Blumenauer, from Oregon, has been trying to change that. Over the summer, he introduced the “Primary Care Enhancement Act of 2019.” It has bipartisan support, with seven Republicans and five Democrats signing on as cosponsors in the House.

In the meantime, Bain and Helman are seeing no shortage of patients looking for a simpler way to get healthcare.

“Healthcare shouldn’t be dominating their worries and their thoughts,” Helman said. “It shouldn’t dominate the national conversation. It’s not that hard.”