PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — The Pacific Northwest is blessed to have a snowy frontier, but there’s more significance to our snowy mountains — our snowpack — than just access for us play in it. Snow is an astonishing winter phenomenon that stockpiles in the mountains. And you can thank that snow for keeping our faucets at ground level running all year long.

Dr. Matthew Sturm is a professor of geophysics at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the head of the Snow, Ice and Permafrost group at the university’s Geophysical Institute. This self-proclaimed old man of snow told KOIN 6 News why snow is like money in the bank.

“What happens all winter is those beautiful snow crystals fall out of the sky and they pile up higher and higher. Most people know that, but they don’t think of it as a free reservoir syncback in the mountains,” Sturm said.

Oregon has thousands of snowcapped mountains dotted around the state but our snowfall among those is greatest in the Cascade Range.

“Nature created a system for humans in the west that was really ideal. Pick up a lot of precip in the winter and stockpile in a natural reservoir. Then let it out slowly just about when farmers and people need it,” he said. “We talk about snow basins that way and all over Oregon and Washington are those basins and virtually all the agriculture takes place down in the lower valleys. But all of the water comes from the higher elevations that needs snow basins.”

Imagine snowpack as money in the bank to spend later in the summer. Snowmelt runoff keeps our wildlife habitats healthy and keeps the crops growing throughout the state.

“Nature created a system for humans in the west that was really ideal. Pick up a lot of precip in the winter and stockpile in a natural reservoir. Then let it out slowly just about when farmers and people need it.”

— Dr. Matthew Sturm

In the Willamette Valley, about 40% of our water supply comes from snowmelt, the rest from rain or ground water. On the east sides of the Cascades, about 50 to 70% of our water is supplied by snow.

A dozen snow basins

Oregon is divided into 12 different snow basins monitored by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, or the NRCS. The NRCS snow survey in Oregon closely monitors snowpack throughout the winter to provide water supply outlooks for farmers and crop owners during the drier seasons of the year.

As of early March, only one of those snow basins is at a healthy capacity, seeing more snow than normal at this point in the winter. The rest of our basins are running lower than normal at 60% to 80% capacity.

“The majority of snow packs, whether it’s in the Rockies, the Cascades, are made up of like 8 events of which 4 or 5 are big ones. It doesn’t take very much to have either bigger, shallow snow pack.”

In our case this winter, we saw about 4 large snow events, all mostly coming in the weeks of December to early January. During that stretch, we received over 9 feet of snow, which boosted our snowpack to a healthy level.

The skiing was grand. The slopes rich with “champagne powder” — and then it dried up.

A lack of fresh snow doesn’t always translate to an unhealthy snowpack. Rather, skiers and snowboarders, shake their first at Mother Nature.

“We might get 8 events, snowfall events that make up the pack. And if one of those is a big event, then it’s a really healthy year. And if not, so that’s always sort of amazed me how touchy the system is. You know, it’s not that you just keep getting it. It’s, you’ve got to get a few key events and then you develop a nice snowpack,” Sturm said.

The abundant snow that came early in the winter looked promising for water supply. However, the current below-normal trend is concerning. In previous years with below normal snowpack, spring snowstorms and rainfall have helped to make up any deficit water. But if dry conditions persist, we should expect more water supply issues this summer.

Tiny Crystals, Big Impact

Dr. Sturm also had a hand in curating the latest exhibit at OMSI called Snow: Tiny Crystals, Global Impact. It’s an easy way to get your kids excited about snow, to understand snowpack and why it’s necessary for Oregon’s way of life and elsewhere in the world.

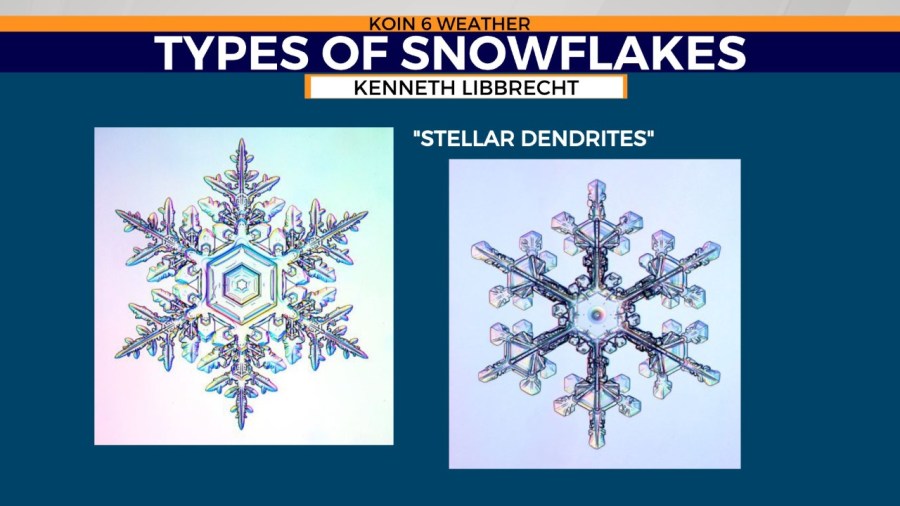

There have been 113 different types of snowflakes identified on earth.

“So they know that snowflake is beautiful. And Christmas is snowflakes. When you say, well, do you have any idea how that beautiful gem-like crystal ended up landing on your jacket?”

Snowflakes form when the water vapor in clouds condense straight into ice, a process called deposition. Some more familiar may be melting, when a solid changes into a liquid, or evaporation, when a liquid changes into a gas.

After deposition occurs, small particles like a speck of dust, start to collect the ice. A crystal is then formed and continues to grow as it flies around the cloud, becoming heavier and eventually falling to the surface.

The one most common that you may recognize is the dendrite, which means tree-like. These have six sides with symmetrical arms.

You can see all the phase changes at the exhibit. The exhibit includes close-up photos of real snowflakes taken by Professor Kenneth Libbrecht from Cal Tech.

Snowflakes can also come in columns or needles or bullet rosettes, some of those can even have capped columns.

So whether you’re a mountain climber like me, with goals to climb the highest peaks in the Cascades, kids building a snowman or you hunker down in town and wait for a snow day or you take it to the streets…..you must admit that Mother Nature did a pretty good job. We get something that’s essential and something that we get to play in.

Snowfall is a natural phenomena that happens all around us, but it’s the bounty we collect in the mountains that we should be thankful for.

Kelley Bayern has spent a decade exploring the highest peaks in the Cascades with seven volcano summits under her belt – and a whole lot more of them on her to do list.