PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) – Nancy Crampton Brophy, the Oregon romance novelist who’s suspected of murdering her husband in the Oregon Culinary Institute in Portland in 2018, appeared in court Tuesday for the second day of her trial.

Crampton Brophy is facing a murder charge for the death of her husband, Daniel Brophy. He was an instructor at the Oregon Culinary Institute, where he was found fatally shot the morning of June 2, 2018.

In court on Tuesday, the prosecution called four people who attended the Oregon Culinary Institute at the time of Daniel Brophy’s death to the stand to testify. They also questioned the lieutenant paramedic from Portland Fire & Rescue who responded to the scene and the criminalist who processed shell casings found at the crime scene for fingerprints.

Here are 6 takeaways from the second day of the trial:

1. Students say it was unusual to find their entrance locked

Saturday, June 2, 2018, started off as a typical day, the four former OCI students who testified in court Tuesday said. However, the first indication that something was wrong was the fact that the student entrance door to the school was locked. Most of the former students who testified said this was unusual. They said Chef Daniel Brophy usually unlocked it before students arrived on campus.

The culinary students who arrived that day said it was especially unusual because June 2 was “live fire” day, a day when they were asked to simulate a live restaurant by taking and fulfilling orders Chef Brophy would place with them. It was a day comparable to a final exam and several students had arrived early to prepare.

Eventually, the other instructor who was teaching that day, Chef Dorothy Sadie Damon, came outside and realized the students had been waiting at the door. She went to get her keys and let them into the building.

2. The discovery of Daniel Brophy’s body

Clarinda Perez had gone to a nearby Starbucks for a coffee after seeing her classmates waiting outside the locked door. In her testimony, she said she returned just as the students were filing into the building. Perez went to fill her water bottle but saw the water jug that Chef Brophy usually filled before students arrived was empty – another unusual occurrence. She went into the kitchen closest to the water jug, Kitchen 1, and found the sink running and Chef Brophy on the floor.

She checked to see if she could get a response from him and when she received none, she ran to the doorway and yelled for someone to call 911.

3. Perez attempted CPR on Chef Daniel Brophy

At the time, Perez was working as a medical assistant and knew CPR; she started chest compressions. When she started, there was no blood visible. Melissa Flitcsh, a pastry student at OCI at the time, said she had assumed Chef Brophy had a heart attack or stroke.

As Perez continued compressions, she began to notice blood.

“His chest was really squishy,” Perez explained between sobs as she testified, “and I thought I had broken a rib because as I continued to do compressions, my hands started getting full of blood.”

She had no idea Chef Brophy had been shot. She thought she caused an open rib fracture, but continued compressions because she’d been taught to not stop, even if she thought she’d broken a bone.

Eventually, she stopped and EMTs and paramedics arrived.

4. Paramedics arrive and make further attempts to revive Chef Brody

The prosecution called Craig Gault to the witness stand. He works for Portland Fire & Rescue and the day of Chef Brophy’s murder he was a lieutenant paramedic in the emergency operations division. He and his team were the first emergency personnel to arrive at the scene. He said they knew they were responding to an unconscious, unresponsive patient and they knew CPR was being performed. He said when they cut Chef Brophy’s shirt open to apply the fast patches for defibrillation, a firefighter noticed a “scratch” on Brophy’s chest.

“It was just a small sort of surface wound with a little splotch of blood, which is common sometimes with penetrating wounds, as like, as they go through the skin [it] will close back up on them,” he said.

Gault said he didn’t realize they had walked into a crime scene until he moved one of Chef Brophy’s arms to place a tourniquet and saw a spent bullet shell casing underneath it.

At that point, Gault realized the cause of Chef Brophy’s condition was likely penetrating trauma, which paramedics cannot resuscitate in the field. That’s when they stopped their medical treatment.

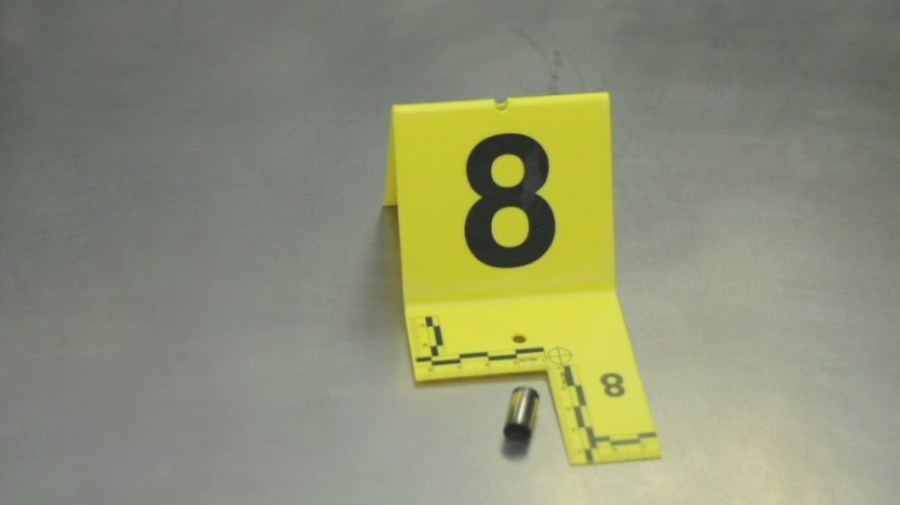

5. Bullet shell casings found

Another firefighter had found a second shell casing and placed it on a table, along with Chef Brophy’s glasses and watch. Gault said he and every member of his team was wearing gloves at the time and would not have left fingerprints on the evidence.

Now realizing they had a crime scene on their hands, Gault said he called in a “code 3” to get police officers to the scene as soon as possible. In his call, he explained there were a lot of people around and he wasn’t sure if the shooter was still in the building. The fire crew at the scene placed the building in a sort of lockdown before police arrived.

6. Shell casings tested for fingerprints

The final person to testify Tuesday was Tina Willard, a retired Portland Police Bureau criminalist. She retired in December 2018 and was working the night of Chef Brophy’s murder. She said a detective asked her to process the two shell casings found at the scene for fingerprints.

Willard described to the court the process by which she processed shell casings for prints. In this case, she placed them in a cyanoacrylate fuming chamber. In the chamber, super glue is heated and releases fumes that adhere to things fingers release, like sebaceous oils, proteins, lotions, or food residue. Fingerprints can leave behind what’s known as a ridge detail.

In her 14 years working as a criminalist, Willard said she’s never found an identifiable print on a bullet shell casing, and the casings found near Chef Brophy’s body were no different.

In the past, she’s found ridge detail, but it has never been enough to identify a print. She said she felt the process is still worth attempting because you never know if some results could lead to a suspect or prove someone was not connected to the crime.

She said wearing gloves would be an effective way to prevent any fingerprints from appearing on a shell casing when someone loads a gun magazine. She did not find any patterns of glove fibers on the casings found at Chef Brophy’s crime scene.

Willard said at the time, it was not standard protocol to test items like shell casings for touch DNA.