PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — As inflation moderates, measures of housing costs remain steady at a high level and a new law in Oregon designed to keep rents in check will likely not contain the problem.

On Wednesday, the Consumer Price Index was released, showing prices increasing 8.5% from the previous year, down from 9.1% in June. However, housing and rental prices, named ‘shelter’ in the report remained at 5.7% higher than 2021, the same rate as in June. Rent specifically was measured at 6.3% higher than last July. Tenant advocates worry about what those prices mean for a rental market already struggling with affordability.

“We’re going to see this huge issue in Portland just get a lot worse,” said Leeor Schweitzer, who handles outreach and advocacy for Portland Tenants United.

Schweitzer worries that, combined with eviction protections ending in Oregon in June, this could lead to many people not being able to afford where they live.

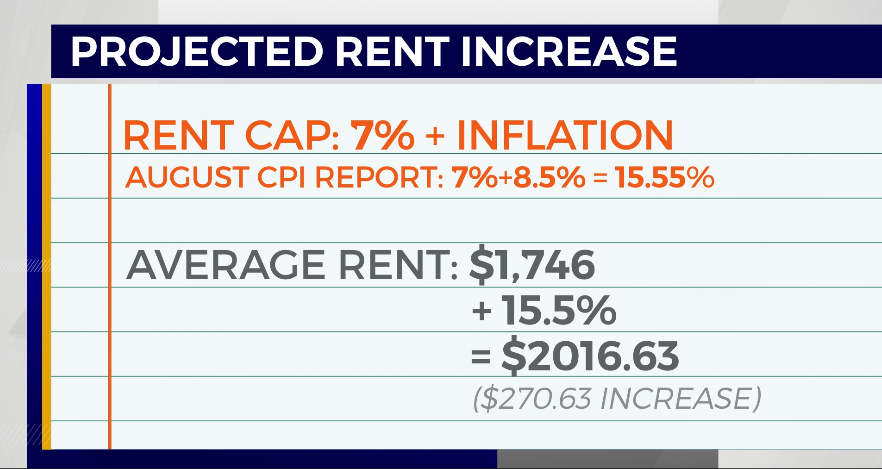

The concern is compounded by Oregon’s recently passed Rent Stabilization law, which creates caps on rent increases. The formula caps rent increases at 7% plus the rate of inflation. The rent cap will be finalized in September, but with the latest report showing inflation at 8.5%, that could mean a 15.5% rent cap, which could push the average price of a rental unit in Portland from RentCafe’s reported average of $1,746 to $2,016.

“Wages are not going to keep up with that,” Schweitzer said. “Most people are going to be earning less than what their rent increases are going to be, even if they are getting some raises.”

Economist Josh Lehner with the State of Oregon says most landlords do not increase their rents to the maximum, but the current shortage of rentals means those unit prices will likely stay high for some time, especially as there has been a slowdown in construction.

“That leaves the rental market very tight. It takes time for new units to be built. It’s likely rental inflation is stronger for longer, keeping overall inflation higher as a result,” Lehner said.

Adding to the constraint on housing are more prospective home buyers chasing fewer homes. Interest rate increases have forced more people to remain in the rental market, says Preston Korst, the director of Policy and Government Affairs with the Portland Home Builders Association.

“You have to think of it as sort of a continuum. There’s shelter all the way to homeownership and what’s getting clogged right now is that rental market,” Korst said.

The undersupply of homes is adding to the clog, Korst says. He estimates the market is 60,000 units short of where it should be, because of 20 years of underbuilding, especially in the years since the great recession.

He says around 8,100 homes were permitted to be built last year. In addition to the 60,000 shortage, there needs to be 220,000 more homes built in the metro area to keep up with the area’s growth over the next two decades. More than 11,000 homes would need to be built every year over that time to keep up.

“The region is going to have to ramp up production to a degree that we haven’t seen since before the Great Recession in 2008,” Korst said.

Part of the problem Korst points to is permitting. It can take months for some jurisdictions to approve new developments, it can be years in others. Each delay costs home builders interest on the land they want to develop and already permits and system development charges can cost between 15 and 25% of the cost of a home, with a dollar amount up to $35,000.

“It’s going to take a regional approach. I don’t think there’s any specific region or any specific city within a region that’s going to actually solve the housing crisis that we’re in and the affordability crisis that we’re seeing,” Korst said.

With that kind of shortage, it will reasonably take years to catch up on the number of units needed. Tess Fields has created an organization utilizing resources already built.

She founded Home Share Oregon and is trying to tie together renters struggling to find a unit they can afford and homeowners with a spare room, or who are financially burdened with their mortgage payments.

She estimates there are 1.5 million homes with a spare room in the state.

“We felt if we could just get 2% of that population to home share then we can house 30,000 people affordably,” Fields said.

In Home Share’s first year, Fields reports that 300 to 500 people were housed. She says they are on track to house 5,000 people in its second year, going into 2023.

She says it’s a more cost-effective approach, as she reports the cost of building a new home or apartment complex breaks down to “about $350,000-$400,000 per door.”

Fields has recently taken in a home share tenant herself and hopes it can provide affordable housing while helping homeowners build financial resilience.

“What we’re dealing with is being able to put to work what we consider to be underutilized housing inventory,” Fields said, “For every single person that chooses to home share, we are making one apartment available.”

Home Share Oregon is conducting a survey to gauge how people feel about seeking a home or taking in a tenant. The survey can be found here.