PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — The partial jawbone, marred by cracks and broken teeth, sat in a museum drawer for decades before Selina Robson came along.

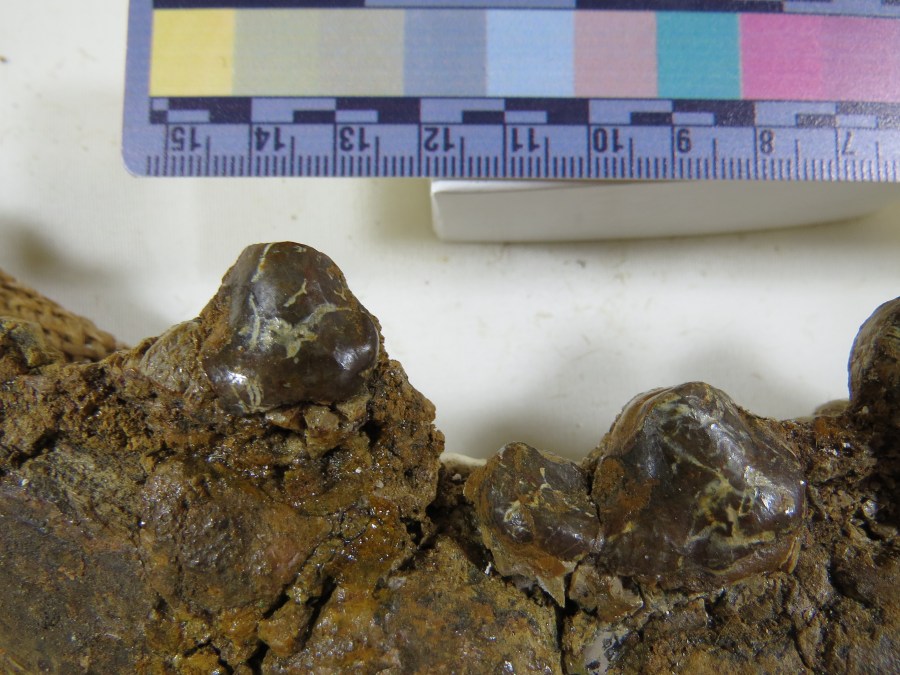

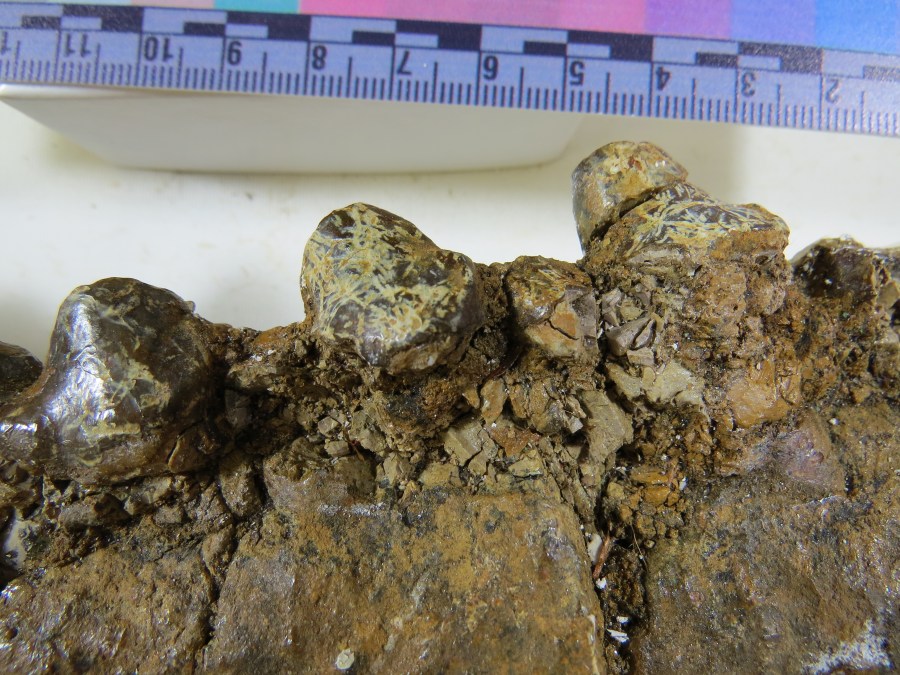

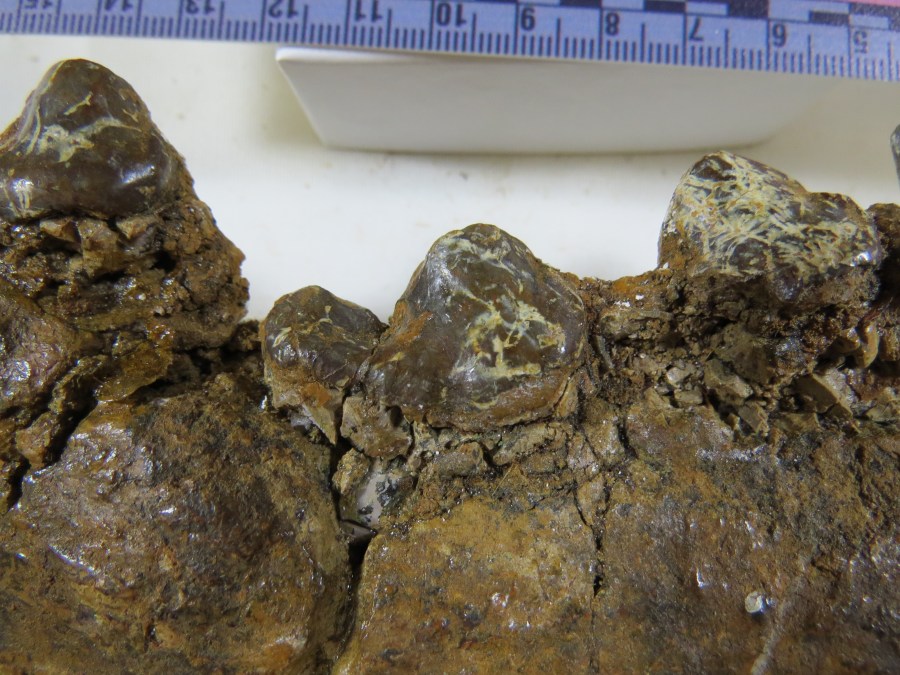

Though incomplete, the fossil was still as long as a human forearm. One side remained encased in rock but Robson could see enough of the jawbone to question whether it had been properly identified in years past.

CT scans helped Robson build a 3D reconstruction that revealed a much clearer picture: the jawbone — unearthed some five decades ago in Eastern Oregon’s Wheeler County — likely belonged to a bear-sized carnivorous mammal with hooves that lived roughly 40 million years ago. It may have looked, in Robson’s words, like a “weird hybrid between a pig and a wolf.”

It was also the first of its kind ever found in the Pacific Northwest.

“Essentially, they were carnivorous,” said Robson. “They would have had fur and superficially, if you looked at them, they would have looked like they had paws but what would have been the claws were actually compressed hooves so they weren’t really good for shearing, more for supporting the animal’s weight. They had a rather stiff spine, like a horse now.”

Yes, it had teeth that were clearly used for eating meat. But whether the animal was an active predator or more of an opportunistic scavenger (like a hyena) remains unknown.

Robson was a senior at the University of Oregon when they first pulled the damaged fossil from the Condon Fossil Collection at the U of O’s Museum of Cultural and Natural History by happenstance while researching an entirely different project. It took time and determination to track down the creature’s true identity but Robson’s work eventually led to a scientific paper published in 2019.

The fossil was excavated at Hancock Quarry, part of the Clarno Formation in the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Scientists first thought it belonged to a reptile, perhaps a crocodile. It was later thought to be a bearlike Hemipsalodon — part of a group of carnivorous mammals called creodonts — but that was also incorrect.

Robson’s work, along with the help of other U of O researchers, eventually revealed the fossil best matched a type of mesonychid called Harpagolestes uintensis. Mesonychids were part of an extinct group of mammals closely related to living hoofed mammals like horses, deer and cows. While mesonychids have been found in California and the Midwest, this marked the first specimen from the Pacific Northwest.

The discovery fills an important gap in the creature’s evolutionary timeline. Scientists believe mesonychids originated in Asia between 65-60 million years ago so the jawbone found in the Hancock Quarry supports the theory that the animals wandered into North America when Siberia was connected to Alaska by the Bering Land Bridge.

Robson, who is now a doctoral student at the University of Calgary, has done more for the world of paleontology than meets the eye. Identifying the remains of a long-dead creature suggests other wrongly-named fossils have been tucked away in museum drawers across the globe. Perhaps they’ll one day get the same chance to expand our knowledge of the prehistoric world.