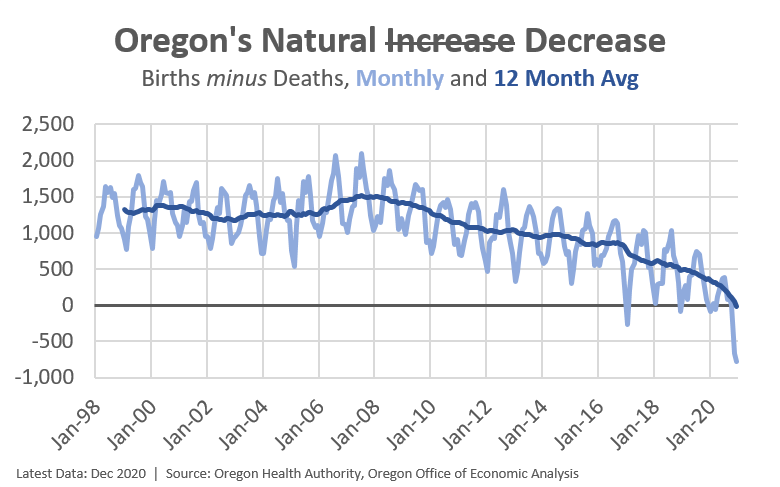

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Oregon’s population trends set a grim milestone last year, with deaths outnumbering births in the state for the first time ever, according to state economists; however, locals in areas with declining populations remain optimistic.

Birthrates are declining across the developed world as a whole, driven by scads of circumstances like job and marital status, income, childcare costs and more; however, Oregon’s decline has happened almost a full decade sooner than state economist Josh Lehner expected, though, hitting a 30-year low.

“Ours is more dramatic than most other states,” Lehner told KOIN 6 News.

The main problem is the decrease in births, but Oregon has also seen an increase in so-called “Deaths of Despair”: Drug overdoses, alcohol-related diseases, and suicide have all increased, offsetting the decrease in deaths brought on by medical advances, according to Lehner.

From an economic standpoint, a shrinking population poses problems as more people age into retirement, infrastructure falls into disrepair, the tax base wanes, and more.

Those effects are already being felt in some rural areas like Grant County, which has seen a steady — but small — decline in overall population. They’ve lost about 14 people a year since 2010, according to estimates from the Portland State University Population Research Center. That’s a nearly 2% decrease for the county of just over 7,000 people.

Infrastructure is decaying, and the county doesn’t have the funds readily available to handle it, Grant County Chamber of Commerce President Sherrie Rininger said.

Bob Quinton, vice president and commercial lender at the Bank of Eastern Oregon, thinks a lack of jobs is one of the major problems facing the county.

“It’s a matter of really not having the opportunity to be here,” he said. “There’s not a lot of professional jobs here unless you’re maybe a doctor or a teacher or work for the forest service.”

Rininger said the county is trying to draw in more young people, but with limited broadband, they haven’t been able to take advantage of the trend of remote work. She also sees the area’s lack of housing as a barrier.

“Our realtors have never been so busy and there is definitely a shortage,” she said. “So we need more homes built.”

Because even if young people are pulled to metropolitan areas for better career opportunities, there’s no shortage of older adults looking to pack up and move to every corner of Oregon, Lehner said.

“Thankfully every corner of our state is beautiful. Every part is scenic. It’s attractive. We get people to move here,” he said. “So even our more hard hit, far flung rural areas have basically stable populations due to that continued inflow of people moving in.”

Inward migration is the only thing growing Oregon’s population. Around two out of every three adults in the state were born somewhere else, Lehner said. The West Coast primarily sees a northern pattern of migration, with Californians largely moving up to Oregon and Oregonians moving up to Washington.

“We lose people to Washington and that’s about it. We gain from everywhere else,” Lehner said.

With Oregon poised to rely on migration even more, economists and those in local government do worry about what will happen if people stop flocking to the state.

“We lose people to Washington and that’s about it. We gain from everywhere else.”

While the possibility of more cities becoming ghost towns is a risk, Lehner predicts the effects of population decline will be much more subtle.

Quinton, who was mayor of John Day from 2005 to 2012, remembers bragging about how there weren’t any empty storefronts downtown. Now, that’s changed. He and Rininger (who, coincidentally, moved up from California) both feel the local population supports the businesses that are in Grant County. If the timber industry continues to shrink, or the forest service leaves, that could be another hit to the population.

However, locals remain optimistic.

“Certainly Grant County is open for business,” Quinton said, whether people just want to visit or move over and start a business.

“We are close knit,” Rininger said. “Even though we’re an entire county that we take care of, we’re a very close knit county and we look after one another and we help our neighbors… We’re all neighbors here.”