PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — A traumatic incident left Jeff Woodward homeless on the streets of Portland for years.

“I lost my wife tragically to suicide,” Woodward told KOIN 6 News. “That kind of sent me on a journey.”

Now he works with the Evolve Street Outreach Team of the Mental Health & Addiction Association of Oregon, which, along with Transition Projects and Central City Concern are the 3 non-profits tasked with forming expanded outreach to the homeless. These Navigation Teams go into homeless camps and help people navigate services that will help them get out.

The new partnership brings different services together — mental health, housing, drug treatment and health care.

Woodward said there is one way to gain somebody’s trust. “By listening to their story. Everyone has one and we lift them up. We lift them up by listening.”

It can take weeks to gain one person’s trust, going back to them in the camp day after day after day. New figures in Multnomah County showed there are 3057 people living on the streets. That’s about 1000 more than were on the streets in 2019.

The reasons for the increase are the lack of affordable housing, lack of mental health treatment and drug addiction — especially the powerful, deadly drug fentanyl.

Fentanyl, Woodward said, “is like a bomb going off in our city. It’s huge.”

Put all of that in a pandemic and the effects were multiplied. COVID and the fear of infection slowed down outreach efforts.

“With COVID, things have really just put people into crisis,” said Daphne Nesbitt of Transition Projects.

Central City Concern summarized the challenges in a blog at the start of the pandemic: “Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Navigation Team’s purpose was to help people transition out of campsites. For now, their message is the opposite. To stay healthy, they are urging people to stay where they are.”

Drew Grabham with Central City Concern looked back on that.

“The social service/health care services sort of retreated to a remote-based telephonic model, which really doesn’t work with this population whatsoever,” Grabham said. “And we’re slowly sort of needing to kind of bring that back into services. So yeah, we’ve sort of had that challenge and how do we keep our staff well throughout all this? It’s scary. COVID was scary for all of us.”

People living in homeless camps repeatedly told KOIN 6 News the same thing: No one has reached out to them for help finding shelter or housing.

A homeless camper named Will put it this way: “They didn’t come in here and help nobody. Like with transitional housing, they didn’t ask nobody. If they wanted shelters, they didn’t ask nobody. If they just said, OK, well you guys have to move.”

What people might not realize is the City of Portland-sanctioned crews who clean up high impact homeless camps aren’t the ones who are doing social service outreach. Often people who are pushed out of one cleaned up camp simply move somewhere else.

But that same city agency in charge of cleanup will advise the new Navigation Teams which camps to go to.

Grabham said the most exciting thing is when someone tells them, “‘I think I’d like to get to detoxing.’ And when someone on this team can be, like, I know how to do that, let’s get you in there.”

The Joint Office of Homeless Services funded the 3 groups with $1.7 million this year. That will allow the groups to expand from one navigation team of 5 people to 7 teams of 3 people.

Grabham knows people might think that is a paltry number. “That might be,” he said. “It is an improvement from where it is.”

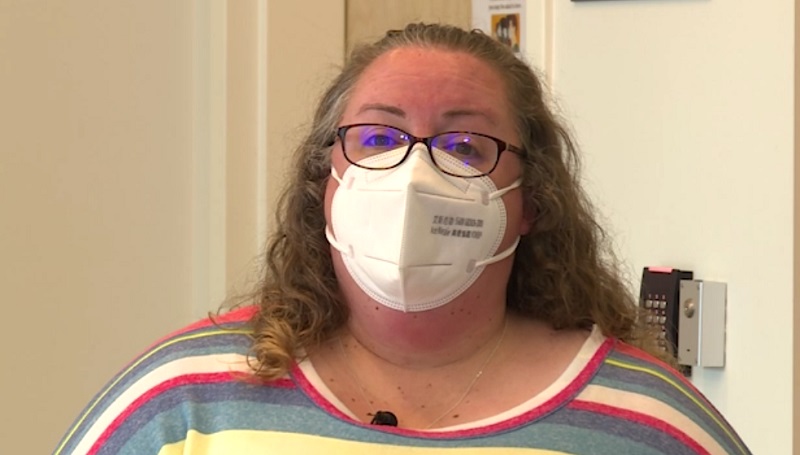

“There’s not enough staff,” said Terry Leckron Myers of the Mental Health & Addiction Association of Oregon. “Twenty-one people cannot take care of all of the high impact camps. So all we can do is the best we can do. And 21 people is not necessarily the end all-be all, but at least it’s going to allow us to take one section at a time. One camp at a time. One person at a time.”

There are 15 total outreach groups funded by the Joint Office of Homeless Services. The goal is to expand the overall number of outreach workers from 47 to 85 this year. The new Navigation Teams will get the most difficult work but it’s been difficult to fill the positions.

The pay is low. COVID remains a concern. And a requirement of the job is to have “lived experience” — either being previously addicted to drugs or previously homeless.

After months the organizations are close to filling all of their positions. But turning the corner on the crisis is still several years away.

“These are people who are living in trauma out there and they’re human beings and we are humans trying to help other humans. And it’s tough work and it’s hard to keep people motivated to come in and continue doing the work when they’re seeing the trauma out there,” Nesbitt said. “And so it’s really important for us as leaders on the team to really make sure that we’re taking care of each other and ourselves so that we can keep coming back and doing the work.”

Having enough shelters beds is key to have some place to take people when they finally accept help.

Leckron Myers said, “The challenges are huge.” Woodward said circumstances “just created this perfect storm.”

“It’s just been relentless, no letting up,” Nesbitt said.

Still, they continue.

“I don’t ever feel hopeless,” Grabham said.