PORTLAND, Ore. (PORTLAND TRIBUNE) — Metro’s 2020 celebration of women’s suffrage could tap an unusual resource for remarkable stories: historic cemeteries.

Portland’s regional government asked the Oregon Heritage Commission for a $9,997 grant to fund half of a nearly $20,000 project researching and highlighting stories of women buried in the Lone Fir and Multnomah Park cemeteries. Commission members meet Monday, Nov. 4, to approve grant funding.

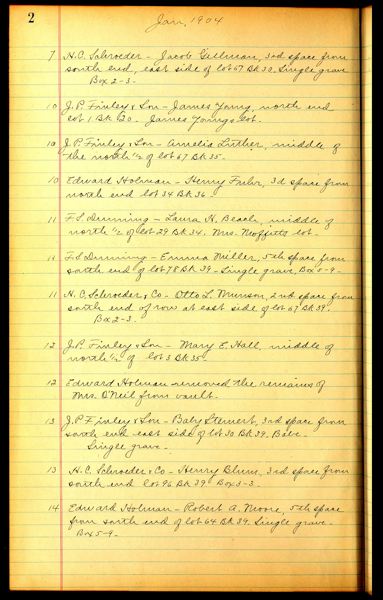

If Metro gets the state money, a full-time researcher will sort through piles of decades-old cemetery records to focus on minority women whose contributions to the suffrage movement and Portland’s early 20th century social changes have long been forgotten, or shoved aside.

It’s sort of a hunt for buried treasure (please forgive the pun).

“We don’t know for sure that we’re going to find a lot suffragists,” said Juan Carlos Ocana-Chiu, Metro Parks and Nature business services manager who is leading the project. “We are confident that based on what little we have found with just the effort we’ve made, we’re going to find some interesting stories.”

Metro’s grant request is one of four dozen applications submitted early this year for more than $519,000 in state funding. Other Portland-area projects seeking funding include $20,000 to complete restoration of a historic mural at Abernethy Elementary School; $18,000 to install interpretive panels on historic buildings in Hillsboro; $17,000 so Portland State University could host a one-day celebration of archaeology and heritage; $7,200 to preserve decades of Portland Youth Philharmonic recordings as the orchestra celebrates its centennial; and, $19,500 to develop information for a Vanport site interpretive center.

Sorting cemetery records

2020 marks 100 years since the 19th amendment gave women the right to vote. Ocana-Chiu said Metro’s proposal began as a regional celebration of the amendment. Metro plans public events in the second half of 2020 at local historic cemeteries to honor Portland-area women buried here who were involved in the suffragist movement. But first, the agency has to find more information about their lives and contributions.

Metro is responsible for 14 Portland-area historic cemeteries. Many of the sites were in disrepair when they were handed off to the regional government in the late 1990s, Ocana-Chiu said. After basic research and sorting through partial burial records, Metro staff discovered that there might be interesting stories about women buried in the Lone Fir and Multnomah Park cemeteries.

Metro’s Historic Cemeteries Team has three staff people dedicated to selling and managing burial plots and maintaining the cemeteries as public parks. The state grant would pay for full-time staff to dig deeper into more than 60,000 burial records and other files, and work with cemetery groups and civic organizations to find the stories.

“We do some research when we can,” Ocana-Chiu said. “Sometimes the community brings us stories and information about people who are buried in the cemeteries, and we use that information. Without the grant we could not dedicate time to just do research.”

Prominent burials

Metro focused on Lone Fir and Multnomah Park cemeteries because those were the two most likely to hold promising historic leads, he said. An exhibit could be created at each cemetery honoring women involved in the social change movement. The project, according to the grant application, is to “highlight the lives of women from historically marginalized communities who, despite being shining examples of strength and self-reliance in the face of adversity, might not have been able to participate as directly in the fight for democratic representation.”

Those include dozens of women from the Morningside Hospital buried in Multnomah Park Cemetery, and about 130 others from the Hawthorne Asylum who were buried in Lone Fir Cemetery.

As an example, Lone Fir Cemetery’s Block 14 holds the remains of Chinese women buried there between 1891 and the 1940s. Some of the bodies were disinterred and sent to Hong Kong for reburial in their hometowns. Many weren’t moved.

When the two-story Morrison Building was constructed on the site in 1952, the remains were supposed to have been relocated. That wasn’t the case. After reconstructing maps of burial sites from hundreds of disorganized or scant records with vague racial descriptions, Metro discovered that the remains of many Chinese women were still buried in Block 14 when the building was constructed, Ocana-Chiu said. “I think that gives us an idea how marginalized they were.”

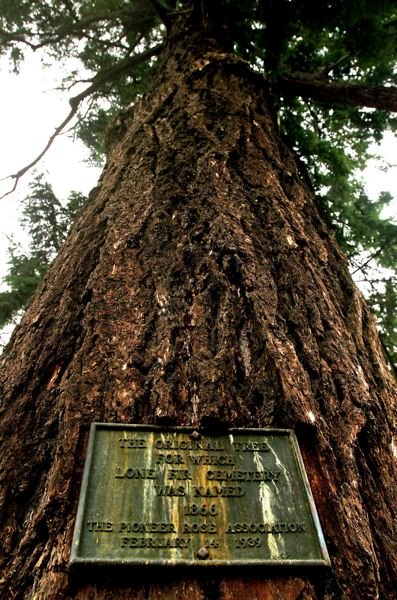

Lone Fir is one of the oldest cemeteries in the region. It opened in 1846 on about 30 acres in Southeast Portland’s Buckman Neighborhood. About 25,000 people are interred there.

Several prominent people are among those, including baseball player Julius Ceaser, whose gravestone features his favorite greeting: “Play ball!” Also buried there is former Mayor James Chapman (1820-1885), who was accused of buying elections and setting up cushy City Hall jobs for his friends. Chapman served three terms. Another is newspaper publisher and former territorial governor George L. Curry (1820-1878). Dr. James C. Hawthorne (1806-1881), who operated a private hospital for the insane on Portland’s east side, is buried there, as were many of his hospital’s patients.

Multnomah Park Cemetery was established in 1888 on about nine acres near today’s Southeast 82nd Avenue in the Foster-Powell Neighborhood. About 2,000 people are buried there. One is land surveyor Robert V. Short (1823-1908), who traveled the Oregon Trail and was a member of the Oregon Constitutional Convention.

Connecting to history

Ocana-Chiu said Metro might turn to crowdsourcing for some of the research. The public often provides information about people buried in historic cemeteries, and tapping the agency’s Facebook and Twitter pages could open more avenues for leads, he said.

Metro is also getting help from the Friends of Lone Fir Cemetery, the Lone Fir Cemetery Association, the Friends of Multnomah Park, the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the Genealogy Forum of Oregon and the Oregon Historical Society. Other information is provided to the agency by the public, Ocana-Chiu said. “We’re asking for the community to be involved because it will help us paint a better picture of how women from all communities contributed to the suffragist movement.”

An example: the story of Mary Jane Holmes Shipley Drake (1841-1925), a child of slaves Robin and Polly Holmes, who were brought to Oregon in 1844 from Missouri. She was part of the 1853 Holmes v. Ford Oregon Supreme Court case that forced her family’s owner, Nathan Ford, to free the children. Because Oregon was not a slave territory, Ford promised to free Robin and Polly Holmes after five years in the state. He kept the children in slavery. Robin Holmes sued to force his children’s freedom, touching off a 15-month trial that ended in the territorial supreme court ruling.

One of Mary Jane Holmes’ descendants told Metro she believed Polly Holmes was buried in Portland, possibly in Lone Fir Cemetery, Ocana-Chiu said.

Even without state funding, Metro could still host events marking the anniversary of the suffragist movement. They likely wouldn’t include life stories of local women who contributed to the cause, Ocana-Chiu said. “We’ve had an interest in doing this additional research all along, we just don’t have the resources to do it.”

One benefit of the research could be a better connection to the region’s historic cemeteries, he said. The public could see them as resources for historic stories, not just burial plots. “I think it will give people a chance to connect with history in a closer way,” Ocana-Chiu said. “If they knew more about these cemeteries and who’s buried there they might be more aware of the local history. That’s one of the reasons we’re trying to get the money to do this, because it will show people there are interesting stories there.”