PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Thought to have been completely wiped out in the state of Washington more than 90 years ago, Washington’s reemerging gray wolf population has officially reinhabited the Southwest portion of the state for the first time in almost a century, experts say.

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife wolf biologist Gabriel Spence told KOIN 6 News that the wolves associated with the new pack named “Big Muddy,” are the first recorded in Southwest Washington since a wolf was killed in Skamania County in 1924.

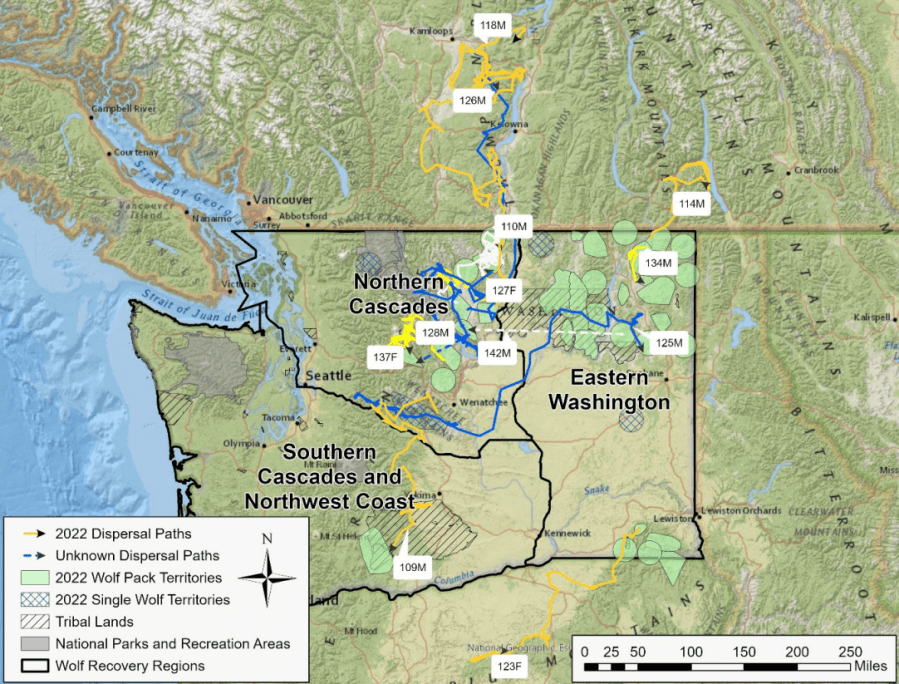

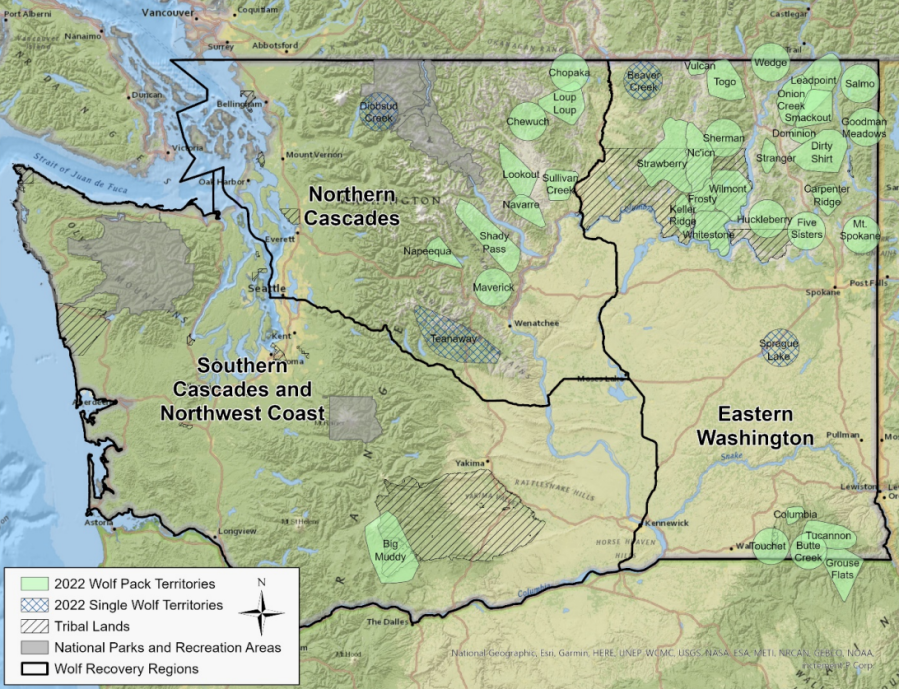

The WDFW outlined the formation of the “Big Muddy” pack that now inhabits parts of Klickitat County in its annual Gray Wolf Conservation and Management report, published on April 7. In the report, the WDFW states that the pack formed after a wolf labeled “109M” left the Naneum pack in Central Washington in December of 2021 and headed south.

In January of 2022, 109M was recorded settling southeast of Mount St. Helens. By the spring of 2022, 109M was spotted traveling with another wolf thought to be his mate, establishing the formation of the new pack.

With Washington’s wolf population growing by an average of 23% per year, Spence said that it’s likely the “Big Muddy” pack will produce cubs sometime this spring. However, no pregnancies have been confirmed within the pack.

“At this point, it’s still just a likely outcome,” Spence said. “About 70% of packs in Washington become successful breeding pairs in a given year. Most packs in Washington have pups starting about now, mid-April until early May, so it might be a little while until we know.”

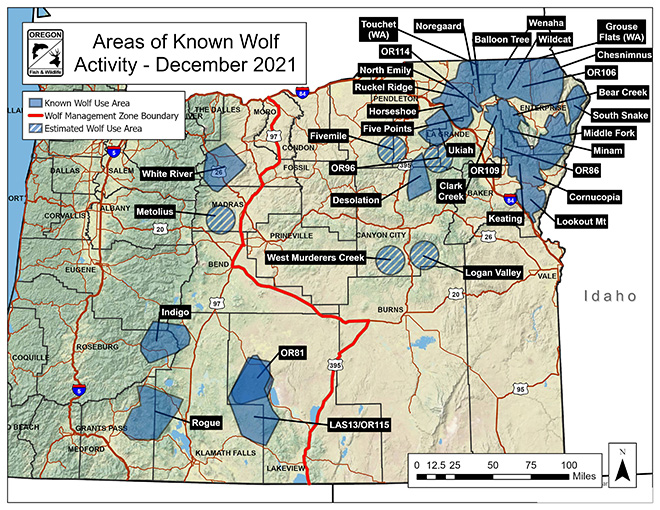

If the Southwest Washington pack continues to grow, Spence said that Washington’s wolf population could potentially continue redistributing south into parts of Northwest Oregon, similar to the packs that have already crossed the border in Eastern Oregon. If any of the state’s wolves were to cut across the river from Klickitat County, their landing spots along Oregon’s neighboring riverbanks include Hood River, Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam and Morrow Counties.

“It is possible,” he said. “Wolves have an amazing ability to disperse across many miles and to cross some pretty daunting obstacles … Wolves are very adaptable and only have a few habitat requirements. Mostly wolves just need adequate prey and a way to avoid human-caused mortality.”

While the immenseness of the Columbia River may seem like a challenging barrier for a wolf, Spence said that human activity along the river may be more of a deterrent.

“We recently had a dispersing wolf cross the Columbia River three times as it traveled across the state,” he said. “The highways and railroads on both sides of the river might make it tougher. I think it would be a rare event for a wolf to cross the Columbia River from Southwest Washington into Northwest Oregon, but it is probably possible. A great example of this happening is the recent wolverine sighting on an island in the Columbia near Portland. Rare, but as we have seen, possible.”

Currently, the closest wolf pack to the Portland metro area south of the Columbia River is Oregon’s White River pack settled near the White River Wildlife Area and Mt. Hood National Forest in Wasco County. If a Washington-based wolf pack were to establish itself in Oregon, Spence said that the responsibility of monitoring the pack would be transferred to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The WDFW report states that gray wolf numbers began to decline in Washington after 1850, when the rising human population began to hunt the wolves for bounties, government-sponsored predator control programs and for the price of their hides. As a result, wolves were listed as an endangered species by the state of Washington in 1980.

Washington wolf sightings steadily increased in the 1990s and early 2000s. However, no native wolf packs were officially documented in the state until 2008. Since that time, wolves have slowly been reestablishing packs throughout Eastern Washington and the Northern Cascades.