PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN 6) — For nearly 17 years, the isolated HOV lane has stretched northbound on I-5 from Going Street to Marine Drive, ending short of the Interstate Bridge.

Portland’s HOV — High Occupancy Vehicle — lane is different than almost every other in this country. It’s short, only goes in one direction and doesn’t get drivers through one of the worst bottlenecks on any interstate anywhere – the bridge.

That is a key flaw.

“HOV lanes should always extend through the bottleneck,” said Robert Bertini, who studied traffic at Portland State University before taking a similar post at California Polytechnic State University.

Three or four days every week, Portland police look for cheaters.

“First thing I’ll look at is, is there someone in the seat next to the driver,” PPB motorcycle Officer Mike Close said.

It’s easy pickings.

There are a lot of explanations and circumstances, perhaps none more legendary than Scarlett Zibritovsky.

She was running late to meet her friends for a camping trip when she was pulled over in the HOV lane with a teddy bear in the passenger seat.

Zibritovsky got a $260 ticket and became Internet famous, even though she insisted the bear wasn’t a decoy but a constant front seat companion.

“It was weird getting thousands of messages via Facebook from hundreds of strangers from all over the world,” she said. “The judge, I remember him telling me, if I had a book of the Top 10 weirdest things that have come through this courtroom, he was like, ‘You would be on page one.'”

According to the latest data from ODOT from November 2013, 23% of drivers in the HOV lane are cheaters.

“About one in four is in the lane that shouldn’t be in the lane,” said ODOT’s Dave Thompson. Their goal is 10%, “and we were there for the first couple years of this HOV lane and it’s fallen ever steadily since.”

ODOT said they don’t have the money to give Portland police to patrol the lane and the PPB Traffic Division says it has other priorities.

“It’s difficult when you only have so many officers,” PPB Sgt. David Abrahamson told KOIN 6 News previously. “You look at 20 years ago and the traffic division had nearly 100 officers working here and working enforcement.Today we have about 30 officers, assigned to our traffic division.”

The HOV lane began in 1998. Data from 2001 shows the HOV lane plus the other two lanes moved 5887 people per hour. But over the years, the number of people getting through northbound I-5 has plummeted. In 2002 it moved 5482 people. 2007 it dropped to 4719.

In 2013, data shows 4527 people got through per hour, a drop of 24%.

But ODOT said the HOV lane is not the problem. Instead, it’s the population jump in Portland. More cars are trying to squeeze through all three lanes, slowing all of them down.

Thompson said ODOT counts people, not cars. “Twice as many people can go through the HOV lane than are going through the general purpose lanes right now. So, moving people through the corridor, more people get through with the HOV lane than would if it were not there.”

Each regular lane carries 1124 people at peak hour. The HOV lane alone carries 2279 people – more than the other two lanes combined.

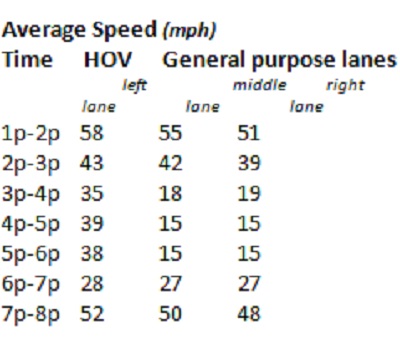

ODOT data from 2014 shows traffic in the HOV lane is moving more than twice the speed of either general purpose lane: 37 mph from 3 – 6 p.m. for the HOV lane, compared to 16 mph for the other lanes.

There is no federal standard for how fast traffic should be going in an HOV lane. A federal minimum of 45 mph only takes effect if the HOV lane become a tolled lane.

Opening the HOV lane to everyone would just make things worse, ODOT officials believe. But there is no way to prove that without doing it.

Washington state scrapped its southbound HOV lane in Vancouver 10 years ago. Even though it was moving more people overall, unlike Portland’s HOV lane it was moving fewer people at the peak of rush hour.

The decision to kill the Vancouver lane was made by politicians. But that does not appear to be on anyone’s radar in Portland, or to make it longer or shorter.

That’s why, 17 years after Portland’s HOV lane was born, it is still considered a pilot project.

“It’s a political choice, always,” ODOTs Thompson said. “These three miles, its future are in the hands of the politicians, not ODOT. Never was.” He said he hasn’t heard any politician talk about it.

KOIN 6 News contacted Portland Transportation Commissioner Steve Novick’s office, the Portland Transportation Bureau, and Metro. All confirmed the HOV lane is not on anyone’s agenda right now.

There is no way to compare traffic to what it was like before the lane became an HOV lane – because that lane did not exist until it was built to be an HOV lane.

Other data about carpooling and bus ridership also does not provide a clear picture of whether the lane is working. The number of people per automobile (excluding buses) decreased from 1.42 in 2005 to 1.26 in 2013. Transit ridership has increased from 1998 by 14%.