CLACKAMAS COUNTY, Ore. (KOIN) — Oregonians will soon decide whether to decriminalize drug use and re-allocate tens of millions of dollars to treatment, or maintain the status quo, as a controversial ballot measure that’s drawn millions of dollars in out-of-state donations goes before voters.

Measure 110 would reclassify personal drug possession to a Class E violation with a maximum $100 fine. It does not affect people selling or manufacturing illegal drugs. People caught with user-amounts of drugs could get the fine waived by completing a health assessment, during which they could be connected with treatment, recovery and housing services. Those services would also be expanded under Measure 110 and funded with a large chunk of marijuana tax revenue.

“… he would still be here if he could have accessed treatment in time”

Community organizer Amelia Fowler says Oregon ranks nearly last of all states in access to drug treatment. The issue is personal for the former Marine.

Her dad was addicted to crack cocaine and died of an accidental fentanyl overdose last November, she said. Throughout his life, he had many run-ins with the criminal justice system, which was traumatic for their family. Despite that, her dad was her “biggest cheerleader,” writing to her every week that she was in boot camp, and seeing her off as she boarded a plane to Afghanistan.

“He was always really optimistic about getting better,” Fowler said. “I fully believe that he would still be here if he could have accessed treatment in time, and the support that he needed.”

Amelia Fowler with her father, who died of an overdose in November 2019 (courtesy Amelia Fowler)

Amelia Fowler with her father, who died of an overdose in November 2019 (courtesy Amelia Fowler)

Janie Gullickson, one of the chief petitioners, spent 22 years addicted to methamphetamine, beginning early in her teenage years. Despite coming from a relatively privileged background, her drug-use spiraled out of control.

“I lost everything and then I became homeless, IV meth user, diagnosed with schizophrenia and living on the streets,” Gullickson recalled.

The only time she got treatment was in prison at age 36, she said. She practiced a new way of life 14 hours a day, seven days a week, for six months. Through it all, she wondered why this treatment wasn’t available outside of prison, Gullickson said.

“The answer that I got … is that it was expensive,” she said. “I wonder how expensive (it) was to not be able to raise my five children, to cycle in and out of emergency department and jail until finally landing in prison.”

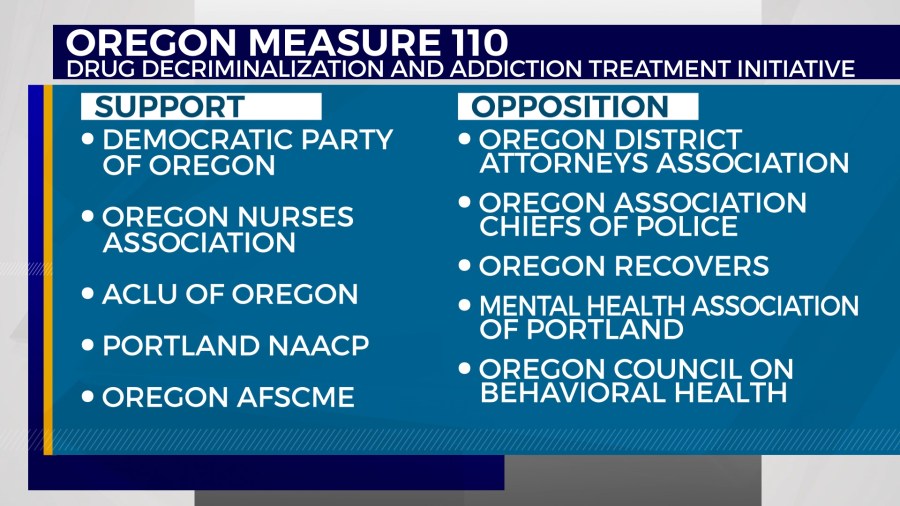

Now she’s sober and the executive director of the Mental Health and Addiction Association of Oregon, one of many organizations backing Measure 110. The Oregon Nurses Association, ACLU of Oregon, Portland NAACP, and the Democratic Party of Oregon are also among the supporters. However, several prominent organizations in the mental health community have come out against Measure 110.

Oregon Recovers says “people will die unnecessarily” if the measure passes, because it would reduce court diversions to existing treatment programs. The Mental Health Association (MHA) of Portland released a statement saying in part that Measure 110 would “dismantle what drug treatment is available in Oregon now” and hurt children by offering them equal protection as adults to possess street drugs. And the Oregon Council for Behavioral Health (OCBH) says Measure 110 “destroys pathways to treatment and recovery” and fails to address the state’s access issues, adding the “significant cross-sector policy changes necessary to achieve these goals” is a task better suited to the Legislature.

“Measure 110 is an idea that on the surface might sound appealing or compelling, but when you look into it, it’s a very dangerous measure,” Washington County District Attorney Kevin Barton told KOIN 6 News.

While Barton agrees the current system is far from perfect, he says making treatment voluntary is not the way to go.

“If you’re addicted to heroin and someone says you can pay a $100 fee or you can enter into treatment to get it waived, there’s a significant chance you’re just gonna do neither,” Barton said.

Drug use can also lead to property crimes, as people look to fuel their drug habit, he added.

“The cost of not doing something, in my opinion, is far greater than the cost of forcing people into supervision and drug treatment,” he said.

But retired Clackamas County sergeant Paul Steigleder disagrees with that argument, saying Measure 110 doesn’t excuse any criminal activity outside of drug use.

He saw plenty of people who struggled with addiction during his 30 years in law enforcement.

“I went from thinking we were doing the right thing by getting these people into the criminal justice system and realizing that we weren’t providing them with the necessary tools to overcome their addiction issues,” Steigleder said. “We need to give our law enforcement more tools to deal with the situation that they come in contact with. When you come in contact with a person who’s struggling with an addiction issue, give them treatment. Don’t incarcerate.”

Racial impact analysis

Earlier this year, state lawmakers requested a racial impact analysis of the bill for the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission (CJC). The CJC analysis results appear in the voter’s pamphlet, and project dramatic decreases in drug possession (90.7%) convictions if Measure 110 passes.

The CJC estimates racial disparities for misdemeanor and felony drug possession convictions would be narrowed significantly if the measure (known as IP44 at the time of the analysis) passes.

Following the money

The measure requires at least $57 million a year in funding, but since it also calls for all marijuana tax revenue in excess of $45 million a year to be directed to the fund, it’s actually estimated to bring in closer to $100 million a year, according to supporters. Millions of dollars that are currently earmarked for other priorities.

“Measure 110 doesn’t add new money into the equation,” Barton said. “I think anyone that takes a hard look at where the money’s coming from would notice that it’s robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

A state committee predicts Measure 110 would reduce the amount of marijuana tax revenue distributed to the state school fund by $73 million, cities and counties by $36.4 million and state police by $27.4 million in the next biennium. It would also reduce the amount originally allocated to mental health, alcoholism and drug services by $36.5 million, and the OHA alcohol and drug abuse prevention fund by more than $9 million.

The committee also expects Measure 110 to save Oregon around $24.5 million on arrests, probation supervisions and incarceration during the next biennium.

“I think it’s a big experiment … It’s a trojan horse measure”

Measure 110 has turned into a multi-million dollar campaign. Almost all of their contributions have come from out-of-state organizations, which Barton considers a red flag.

The Drug Policy Alliance, chaired by George Soros, has donated close to $4 million to the campaign. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Advocacy is the next highest donor at $500,000.

“I think it’s a big experiment. I think they’re doing it to see if they can get Oregonians to fall for it,” Barton said. “It’s a trojan horse measure where it looks … like it’s focused on rehabilitation and treatment which is wonderful.”

In reality, though, Barton believes it’s one of the largest changes in Oregon’s criminal justice system in decades, decriminalizing hard drug possession without forcing people to get treatment.

“And it’s supported by a group of people who don’t live here and don’t have skin in the game,” he said. “If it works out then that’s great. If it doesn’t work out, then it’s not their problem.”