PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — This past Wednesday afternoon, the University of Portland removed the statue of York from campus.

In response to an email from KOIN 6 News, school officials said that, recently, the statue had been graffitied and threatened on social media. They moved the statue, along with the rest of the monument which featured explorer William Clark and an unnamed Native guide, to a storage facility to keep it safe.

Other statues around town associated with slavery or slave ownership have been vandalized or torn down over three weeks of recent protests.

Portland and Oregon, and the United States at large, is the middle of a modern-day racial reckoning. And, to some extent, for those of us in Oregon, it has historical roots all the way back to the time of Lewis and Clark.

One of the first non-Indigenous, non-white people to set foot in Oregon did so in 1805. He was a man named York. He had no last name. He was enslaved by William Clark.

Forty-three years or so after Meriwether Lewis and William Clark made it to the coast at Fort Clatsop, Oregon became an official territory of the United States.

And, it was born white.

Oregon’s history is “racist at the foundation,” according to Dr. Angela Addea, a University of Oregon School of Law assistant professor, who described early Oregon in a Thursday afternoon webinar focused on providing historical context as it applies to the modern Black Lives Matter movement. It was hosted by the Oregon Historical Society and the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education.

According to Addea, the racist seeds planted at the time of Oregon’s birth, first as a territory in 1844 and then as a state in 1857, continue to bear poison fruit in 2020.

“The violence is and always has been against Black people,” Addea said. “It is the language of communication to Blacks: You don’t belong here.”

So, how did Oregon go from white by design to Black Lives Matter?

Oregon’s, and Portland’s, history of the last 175-plus years is heavily dotted with legalized racism, hate-fueled violence and moments of protest against it. There were lash laws designed to keep Black people from settling in Oregon, a lynching, the Ku Klux Klan, inequitable housing regulations and police shootings on one side. With the formation of the NAACP, a fight against racist propaganda, the Black Panthers and Black Lives Matter on the other.

Tremendous work by the Oregon Historical Society and extensive research by Walidah Imarisha published as a timeline by Oregon Humanities helped KOIN 6 News examine the path from York’s arrival in the early 1800s to what is happening today.

One of the first Portland-based protests centered around race that garnered national attention started in 1915 when Beatrice Morrow Cannady led more than a decade’s worth of demonstrations to limit showings of the KKK propaganda film The Birth of A Nation in Portland.

Cannady would go on to form Portland’s chapter of the NAACP, the first west of the Mississippi River.

While Cannady was on her crusade against the film, the Klan was finding fertile ground in Portland.

By 1921, the KKK had officially established an outpost in Oregon. According to reports at the time from The Advocate and the Portland Telegram, ranking “Kluxers”, wearing their full racist regalia, met with city officials, including the mayor to outline their political objectives. Which, they said at the time, were focused on being more anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic, than anti-Black.

Meanwhile, during the 1920s, city leaders, real estate developers and bankers enacted redline rules designed to limit neighborhoods where Black Portlanders could own homes, forcing them into neighborhoods in inner-Northeast, closest to railways and industrial areas.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, thousands of Black shipyard workers flooded into Portland to build the U.S. Naval Fleet that would win the War in the Pacific. Most of them lived in Vanport. Following the war, a lot of them stayed.

Three years after the war ended, so did Vanport. A massive flood wiped out the city and forced thousands of Black people to find new places to live.

Once again, the majority of Portland’s Black population was forced into Northeast neighborhoods with names like Albina and King, Irvington and Alameda.

Within a decade, those same neighborhoods would start becoming sites for major transit projects and entertainment venues. Moves that displaced thousands of residents. A new hospital, shopping centers and high-rise condo developments would follow by the end of the century, driving up property value and leading to the erasure of entire Black communities.

“Gentrification is a part of this legacy,” Dr. Addea explained. “We are living out this history right now.”

While gentrification was already underway, a series of laws passed between 1949 and 1957 afforded Black Portlanders more rights in employment, lodging and housing and signaled the slow arrival of the Civil RIghts movement in the city.

While no one would say police treatment of Black people in Portland was anything that resembled proper up until the mid-1960s, tensions finally boiled over into riot in 1967. A rally for civil rights turned into civil unrest and hundreds of disenfranchised, young Black people battled with Portland Police in the Albina neighborhood. Rioters throw rocks and bottles at officers, businesses burned and damage estimates topped $20,000.

Another Albina riot, similar in scope, followed two years later.

Between the two Albina riots, Portland’s chapter of the Black Panthers was born. While the organization was often considered anti-police and anti-white, the Panthers funded education programs, clinics and provided food for kids in need.

“[The] Black Panthers of Portland were an incredibly successful, long-lasting chapter,” said Judson Jeffries, a professor of African American Studies and African Studies at The Ohio State University. He also took part in Thursday’s webinar hosted by the Oregon Historical Society and the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education.

The arrival of the Black Panthers in Portland, and the two riots in Albina, added to the building tension between the Black community and Portland’s police force. By the time the early 1970s rolled around, mistrust between the two communities boiled over into several, high-profile incidents that dominated headlines for the next three decades.

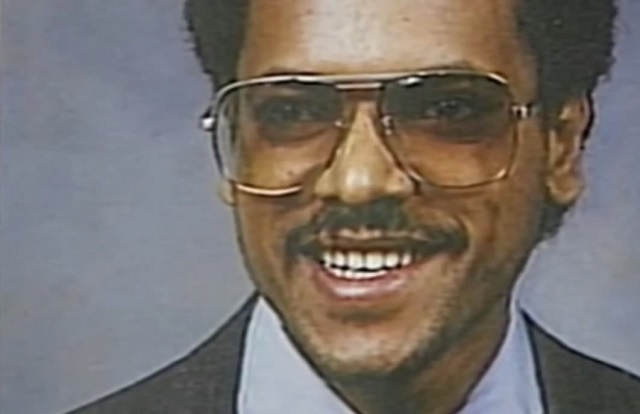

Incidents that included the 1985 death of Lloyd Stevenson. The former Marine was killed by an officer using a chokehold following a disagreement in a parking lot in Northeast Portland. Use of the chokehold, nicknamed the “Portland Sleeper,” was banned shortly after Stevenson’s death. Neither officer at the scene was charged.

The 1980s also brought a familiar and unwelcome movement to the Pacific Northwest. White supremacy groups once again found fertile ground on which to build their dreams of a white homeland. Instead of the KKK, this time the group called themselves the White Ayrian Resistance (WAR).

During Thursday’s webinar focused on providing historical context as it applies to the modern Black Lives Matter movement, University of Oregon Political Science professor Joseph Lowndes explained why the group targeted the region for development and made a home for themselves in Portland.

“Since the 1980s, this vision of a White Nationalist state, there have been experiments in the Northwest to set up white exclusion zones,” he said. “Cities that were less than 10% Black were easy to organize in.”

The 1988 murder of Mulugeta Seraw, an exchange student from Ethiopia living in Portland, put the spotlight on WAR. The conviction of his killer and the separate conviction of two WAR founders for inciting violence against Black people all but ended the resistance.

But, the gentrification went on in Northeast Portland. As developers purchased more property for new, high-end housing developments, families that had called Albina and Alameda home for a generation or more were forced to move west, into the suburbs of Beaverton, Hillsboro and beyond.

Over the next 20 years, as Black neighborhoods in the city shrank, the disconnect between Portland Police Bureau and the community it was supposed to be protecting and serving seemed to continue growing. More Black Portlanders died at the hands of Portland Police officers. More protesters took to the streets. More time went by.

In response to the 2012 shooting death of Trayvon Martin in Florida, a new thread appeared on social media: #BlackLivesMatter. The subsequent deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and Eric Garner in New York City, both at the hands of white police officers, pushed the hashtag into the national spotlight.

In a city known for both protests and an historically troubled relationship between police and the Black community, the Black Lives Matter movement found a home and a voice in Portland too.

While a series of recent, violent incidents on the streets of Portland, following the election of President Donald Trump in 2016, the inauguration of President Trump in 2017, did not include officially organized participation by Black Lives Matter protesters, the movement continued to grow and gain in popularity.

That popular movement exploded in 21-straight nights (and counting) of protest following the May 25, 2020 killing of George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

An original posting of this article on KOIN.com omitted crediting Walidah Imarisha for her amazing work in researching and writing a timeline that was published by Oregon Humanities that served as a road map for this story. The author regrets the error.