PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — It may surprise you to find out just how much our societal response to the novel coronavirus pandemic is similar to another pandemic humanity faced 100 years ago: the 1918-19 influenza outbreak.

“Since we don’t have a treatment, despite all of our medical advances…we don’t have a vaccine, we’re stuck with early 20th century social and political responses,” said Oregon State University Director of the Center of the Humanities and Associate Professor Christopher McKnight Nichols.

Similar to today, many large cities around the world enacted what are called “non-pharmaceutical interventions” to help mitigate the spread of the 1918 flu, like social distancing, quarantine measures, closing theaters, schools, and restaurants and limiting the number of people on public transport.

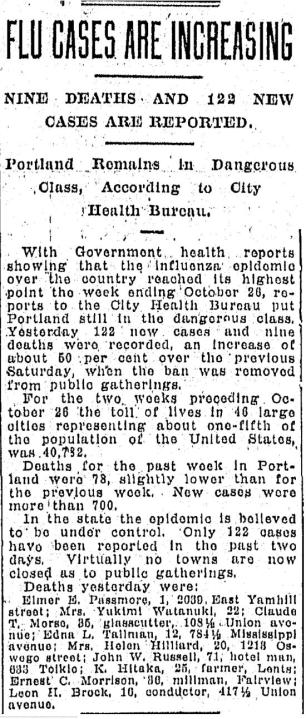

In Portland, for instance, the city required a distance of four feet between people in public, enforced by police and firemen, according to a November 3, 1918 issue of the Sunday Oregonian. The city council even once attempted to make wearing flu masks mandatory, but the emergency clause failed to pass, a January 16, 1919 edition of the Morning Oregonian stated.

Unlike today, those non-pharmaceutical interventions were only enacted on a large scale in the midst of the second and deadliest wave of the virus, in fall 1918. The virus came in three waves, first in the spring of 1918, then fall of that year and later spring of 1919. In the end, it infected 500 million people worldwide and killed an estimated 20 million to 60 million people.

By contrast, as of this writing, the novel coronavirus has infected about 3.9 million people worldwide and caused 265,862 deaths, according to a May 9 World Health Organization report.

The biggest take-away from 1918-19: large cities that closed all at once, stayed closed longer, and reopened in a phased or layered approach–not all at once–tended to do better in terms of avoiding infections and deaths.

The data is pretty conclusive, Nichols said, because “it was in the midst of a war, data was being collected like crazy. We know a lot about this. A very fine grain analysis has been done by doctors and PHDs and all kinds of folks, from the 1920s all the way up to the present.”

A research paper comparing how different U.S. cities who implemented various levels of non-pharmaceutical interventions in 1918 concluded that it found “a strong association between early, sustained, and layered application of non-pharmaceutical interventions and mitigating the consequences of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in the United States.”

The scientific knowledge of microbes was far enough along in 1918 that people knew to clean surfaces with soap and water, for instance, and that the disease could be spread through sneezes and droplets in the air, Nichols said. But they also had a lot of misinformation, like the idea that the flu could be transmitted over the phone or that so-called “cures” like using Vick’s Vaporub, hard alcohol or gargling salt water worked as a remedy.

Accounts of 1918 flu cases were based on doctor’s observations, not on any tests. In fact, they didn’t even know it was a virus because viruses weren’t discovered until the 1930s when they had powerful enough microscopes, according to an article on Web MD.

Similar to today, many government entities suggested or even enforced that people wear cloth masks in public. And just as it is today, there were also protests for government’s orders to the public. In San Francisco, that took the shape of the so-called “Anti-Mask League,” an organization of about 4,000-5,000 who protested the city’s mandatory mask order, Nichols said.

A Second Wave?

Though Nichols clarified he is not an epidemiologist or M.D., the potential for the novel coronavirus re-emerging as a second wave is his “biggest worry as a historian.”

Scientists also fear a second wave may bring untold devastation if states and countries choose to re-open too quickly.

Back in 1918, the “vast majority of deaths happened in the second wave, which is in the fall of 1918 as it’s getting colder” Nichols said.

Nichols’ take-away: Should cities and states be able to hopefully open up, the thing to do is to be tracing and look at testing.

“The second that you see things going up, the lesson from history is, immediately close down. That’ll help prevent the spread, at least until there’s better treatments.”

Contact Tracing: Then and Now

Oregon Governor Kate Brown announced her criteria for counties to apply for reopening this month, as did Washington Governor Jay Inslee. Both include plans for testing and something called “contact tracing.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control, contact tracing involving public health staff working with a suspected or confirmed patient of COVID-19 and helping them recall everyone with whom they have had close contact with. The health workers then give those individuals education and guidelines to isolate from others to mitigate the spread.

Public official did enact contact tracing in cities back in 1918, Nichols said. In Portland, that involved then out of work public school teachers visiting apartments and houses of known flu patients to educate them on so called “ventilation and hygiene,” often from the street and communicating through an open window. They would then try to figure out who the patient had been in contact with.

Though the contact tracing process wasn’t as rigorous as it is today, even then it was considered “well known in medical history and in public health: you need to look up the contacts of people who have the disease and try to figure out how to limit multiple sets of network connections,” Nichols said.

Election Year During a Pandemic

It may surprise you to know that 1918 was in fact a national election year. Unlike the upcoming 2020 presidential election, however, it was a midterm election at the congressional and state levels.

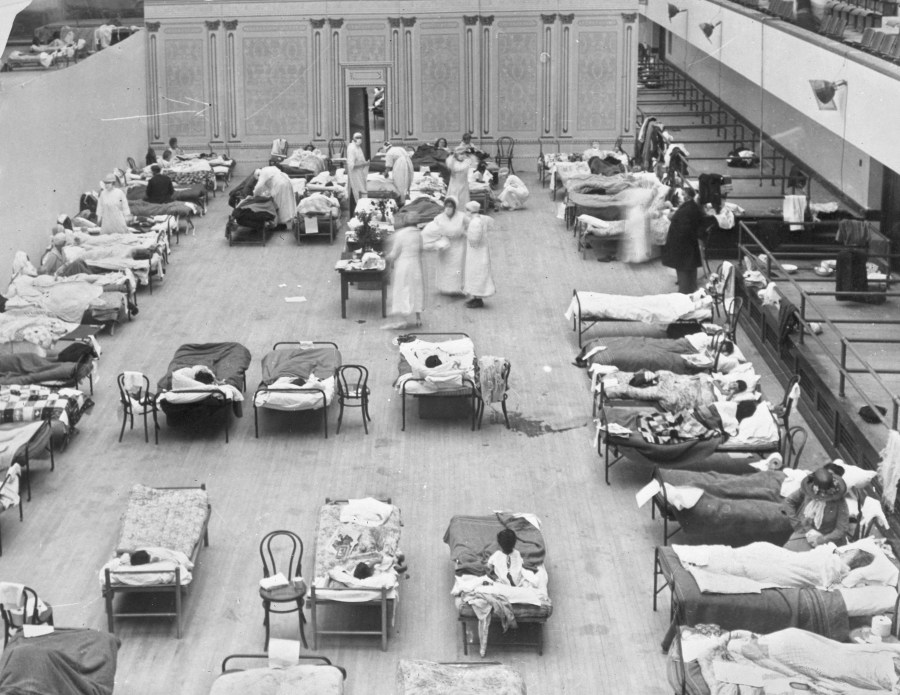

There was a reduced voter turnout and likely transmission of disease, and subsequent deaths, through voting as a result of the November election hitting right in the midst of the 1918 flu’s second wave. Redcross nurses even had to man some of the voting polls.

The proposal of voting by mail for the national stage is one that is championed by Nichols, who said he thinks if such a measure were could be achieved in 1918, it likely would have gained bi-partisan support to “ensure safety and use other, alternative means of voting.”

He said that’s a striking contrast to today, where the idea is sparking tense partisan debate in Washington.

Oregon has being doing vote-by-mail for every election since a ballot measure was passed in 1998. Oregon U.S. Senator Ron Wyden introduced a bill back in March to allow all states the option for vote-by-mail.

Xenophobia and Scapegoating

The 1918-19 flu pandemic is colloquially known to as the “Spanish Flu,” but it may surprise you to know that most public health experts and historians agree that the most virulent form of the virus “almost definitely” arose in an obscure county in Kansas. It was then transported to a major military barracks and from there, traveled globally due to World War I troops travels, Nichols said.

The misnomer arose in the U.S. and Britain in part due to xenophobia and politicization of the virus. Spain was a neutral power in the war and “were thought by the British and U.S to be sympathizing with the Germans and Austro-Hungarians,” Nichols said.

It was also heavily documented by the Spanish press that Spain’s King Alfonso the 13th had come down with the illness in May 1918. In the U.S. and Britain, anti-espionage laws prevented the media from publishing things that might undermine the war effort.

Nichols said it’s a fascinating moment in history that illuminates what’s going on today.

“A virus as the ‘invisible enemy,’ as Trump calls it, is hard to conceive of and fight. But if you make it a ‘Chinese Virus,’ then you can racialize and politicize it and kind of weaponize the term and concept of the flu or the virus itself.”

President Donald Trump used the term “Chinese Virus” to describe COVID-19, denying that it could risk causing hate crimes of Asian Americans to occur.

Nichols noted that some of the most “draconian” and sweeping anti-immigration acts in U.S. history were passed immediately following the 1918-19 flu pandemic, in 1919, 1921 and 1924.

Lessons for the Future

While there are many parallels from 1918 to today, one notable distinction in our age regarding government response to COVID-19 is the existence of coastal state pacts.

On the west coast democratic governors from Washington, Oregon and California agreed to coordinate with each other their decisions to reopen each state. It followed from a similar pact of east coast states New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

Such pacts were not contemplated back in 1918-19 because people didn’t demand public health solutions in the same way, Nichols said.

“If these regional blocks are effective, as conduits for public health policy, what does that say about the federal government’s role in the future? Will it be more of a backstop or a confederation than a united states in these kinds of situations?”