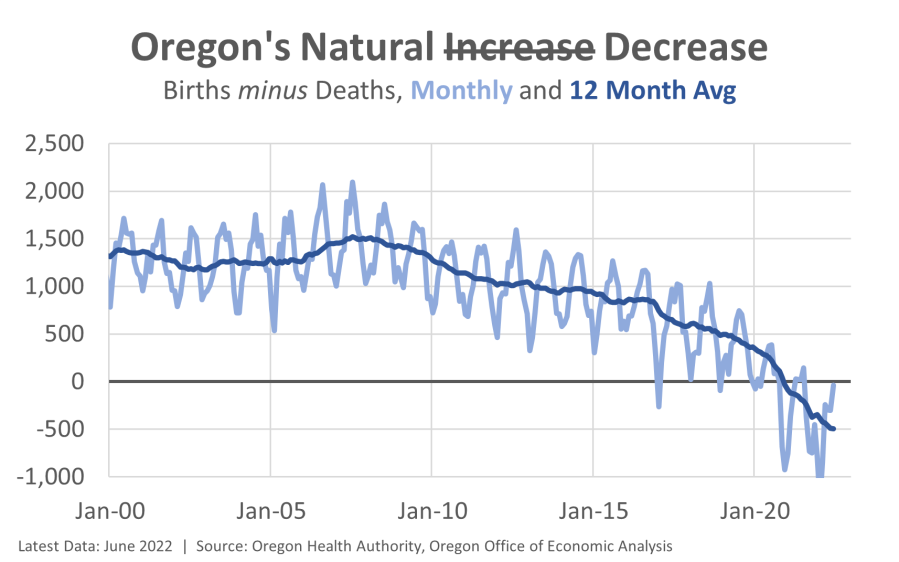

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) – For the first time in recorded history, Oregon deaths are outpacing births.

The birth rate in Oregon had been declining for more than a decade, but plunged during the pandemic, according to recently shared data from the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. While some rural parts of the state have seen deaths outnumber births for the last decade or two, this is the first time the state as a whole has experienced it.

Josh Lehner, an economist with the state of Oregon, said the new trend can be summarized with one word: “yikes.”

“I think it’s worrisome and I think it’s something that’s obviously going to stay with us for a while,” he said. “In our forecasts, we have deaths outnumbering births forever in Oregon.”

It’s alarming because it means Oregon is relying on migration to increase its population and ultimately, to continue fueling and running its economy. A lower birth rate means fewer new workers 18-20 years down the road.

So, what’s causing the change in these vital statistics?

The pandemic is partly to blame.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, the number of weekly deaths has exceeded historical averages since March 2020.

However, even after COVID-19-related deaths are subtracted from the total Oregon deaths from Jan. 1, 2020 through July 24, 2022, the number is still significantly higher than the average number of deaths reported in the state between 2017 and 2019.

Lehner said this could be because larger generations are getting older and dying. As the largest generation, the Baby Boomers, enters retirement age, he expects the death rate will only climb in the next two decades.

Data from the Oregon Health Authority show that the three most common causes of death are cancer, heart disease and unintended injuries. Deaths from all three have increased in the last decade.

Deaths from cancer increased by more than 8% between 2010 and 2020. Heart disease deaths rose by 19% and unintended injury deaths increased 58%.

While deaths are contributing to the problem, Lehner said the long-term shift in demographics will be caused by the declining birthrate.

He said according to the data, people are still having children. They’re just having one or two children instead of two or more.

“That’s really where most of the shift we’ve seen happens, where people are still having kids, they’re still having families and things like that, but they’re just choosing to have fewer kids than in the past,” he explained.

He said the cost of housing, health care and other expenses have contributed to parents’ decisions to keep their families smaller.

Oregon saw a small increase in its births late in 2021, but Lehner said preliminary 2022 numbers show the rate is decreasing again.

This declining birth rate will be noticeable in Oregon’s child-related activities and services, including education and child care. The Oregon Office of Economic Analysis predicted a 6% decline in the K-12 population from 2020 to 2030, even before the latest data.

The decline in younger children could ease some of the strain on Oregon’s pre-K and childcare providers, Lehner said. All 36 Oregon counties are considered child care deserts for infants and toddlers, meaning there are three or more children for every one child care slot available. All but 11 Oregon counties are child care deserts for preschool-age children.

Lehner said fewer children in the future could bring the demand for child care down closer to the number of available slots.

Higher education institutions should also prepare for lower enrollment in the 2030s. Like the rest of the state, Lehner suggests they look to recruit students from out-of-state or abroad if they want to keep their enrollment numbers up.

Oregon has already felt the strain of worker shortages as the pandemic eases. Many Baby Boomers retired, leaving employers scrambling to fill gaps. For the most part, Lehner said, everyone in Oregon who wants a job has a job, and the state has near-record-low unemployment rates.

In the future, businesses will likely continue to compete over the tight labor market and will have to come up with innovative ways to increase their productivity.

“We need more business investment and we need more robots and productivity for future economic growth in general. And today’s certainly a good example of that,” Lehner said.

Luckily for Oregon, there’s been a steady migration stream boosting the population and the migration is expected to continue in the coming years. Lehner’s forecasts predict the population will accelerate in 2022 and 2023 and hold steady after that.

Portland State University will release its population estimates in November and the U.S. Census Bureau will release them in December, which will give a better idea of if people are still moving to the state.