Editor’s Note: KOIN 6 News will host “The Unsheltered Truth: Searching for Solutions” on Wednesday, Sept. 21, at 7 p.m. with local lawmakers, non-profit leaders, experts and neighbors for a town hall discussion on the homeless crisis.

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — The crisis of homelessness in Portland is the talk of the Oregon governor’s race, the election around Portland’s form of government, and on top of the mind of voters. KOIN 6 News is taking an in-depth look at what factors lead people into homelessness and what prevents them from leaving.

The financial accessibility of housing is one of the leading factors that either puts people on the brink of homelessness, or pushes them over that edge, according to Dr. Marisa Zapata, a professor at Portland State University and director of its Homelessness Research & Action Collaborative.

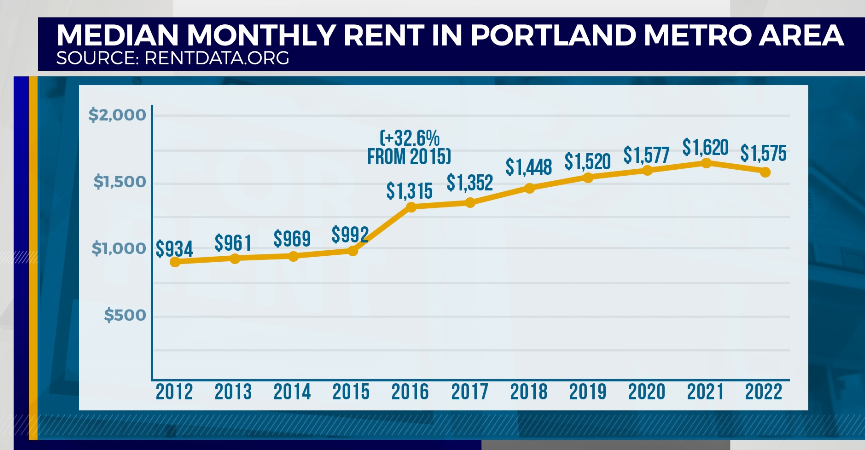

The median rent for a two-bedroom home has increased 68.6% since 2012, according to data from Rentdata.org. In 2016, rent skyrocketed 32.6%, far surpassing four figures to a median of $1,315.

“It’s the combination of escalation in rents, as well as rising rapidly that become a particular issue when we’re thinking about people who are going to lose their housing, people who are precariously housed,” Zapata said.

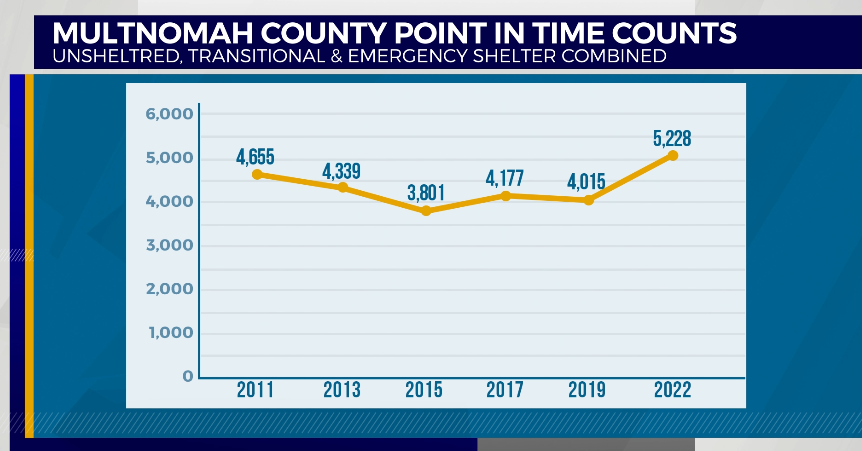

In an effort to grasp the scope of the issue, Multnomah County has conducted point-in-time counts nearly every other year — the pandemic pushed the latest count from 2021 to 2022.

The widely-used metric is also widely recognized as flawed. Zapata as well as Tony Bernal, the senior policy and financing at the organization Transition Projects, say it’s impossible for the count to find everyone who is homeless, saying it is easy to miss people living in cars, driving around, people living in other people’s homes or squatting in abandoned buildings.

The latest count found 5,228 people living outside, in transitional housing or emergency shelters.

“We’re actually thinking about tens of thousands of people who are actually experiencing homelessness because people tend to focus on who they see on the street,” Zapata said.

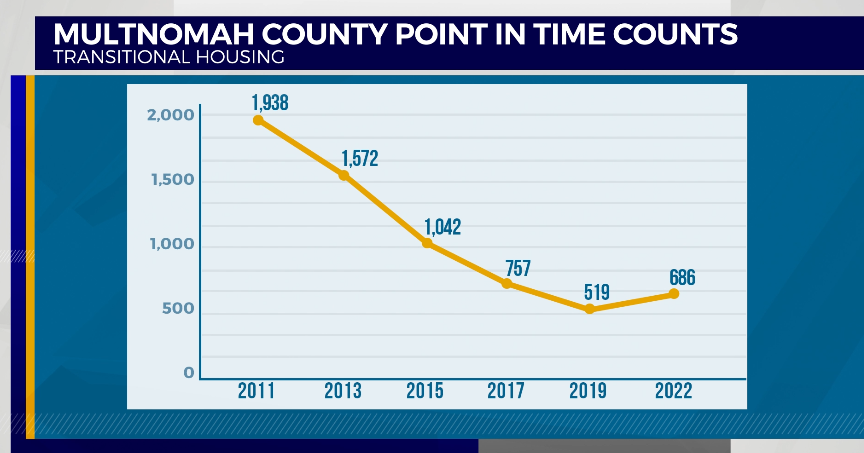

That marks a 12% increase in the number of people considered homeless though, where those people are living paints a story unto itself.

In that same time, there has been a 64% decrease in people living in transitional housing, from nearly 2,000 11 years ago to less than 700 in the latest count.

Bernal and Zapata agree that a lack of federal investment in housing and building affordable units has accentuated the problem of accessing a home.

“We don’t have the kinds of resources that we need to either build affordable housing or to operate it,” Bernal said. “The resource we know works, such as Section 8, are not available as we need them to be.”

Bernal points to estimates showing just 25% of people who have applied to Section 8 have gotten the assistance. He notes that many of the people who are homeless that the organization helps are on fixed monthly incomes from Social Security or Social Security Disability. The Social Security Administration reports an average monthly benefit of $815, compared to Rentdata.org reporting the median cost for a studio apartment in the Portland Metro area at $1,415.

“Income doesn’t match the rents and I think that’s a fundamental problem that we have,” Bernal said.

Services like shelters had been cut, either to spacing or funding, during the pandemic. Mercedes Elizalde, the public policy director at Central City Concern says housing is “the predominant factor in housing,” and that “everything is a risk factor.” She says preventing the people most vulnerable to losing their housing begins with assessing their means.

“Prevention is largely a condition of how much money do people have and how much does housing cost and as long as housing continues to outpace the amount of funds folks have, then anything else in their life … is going to become its own risk factor,” Elizalde said.

The bottleneck and shortage of affordable units relative to the need in Portland is a situation mirrored for access to treatment for both mental health and substance abuse.

Oregon fell to the lowest ranked state in the U.S. for access to treatment from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The state was ranked 47th before the pandemic. Of the Oregonians seeking care, one in five are not getting it.

“We don’t have a system set up services that is immediately responsive and can triage people and get them the help they need,” said Tony Vezina, the executive director of 4D Recovery, a peer support recovery center.

Vezina is in recovery from addiction to prescription pills that once brought him into homelessness. He first found himself without a home at the age of 15. His recovery started and stopped several times, and one of the hurdles was an inability to get into detox or treatment at the moment he was willing to go. Looking back, he thinks incentives helped support him along in the process.

“There are these points in people’s lives who are addicted to substances where they are at a crossroads or they’re considering a change … at those moments, that is where we need to have access to treatment and recovery services immediately,” he said.

Rather, a shortage of detox beds to get people to a stabilized and sober level, combined with a lack of addiction treatment beds, stops people from getting their recovery from the beginning. Vezina said the people who are wanting recovery that he has worked with have faced wait lists that are days, weeks, and even months long.

“The problem is [care facilities] are so fractured and disconnected that you can put someone in a treatment center for 28 days, they can do a really great job, but they open the door and that person goes out and they’re not connected with post-treatment support,” said Mike Marshall, the Executive Director of Oregon Recovers.

In 2018, Vezina and other leaders in the substance abuse realm were convened by Governor Kate Brown as part of her Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission. The team made recommendations about creating a more seamless continuum of care, around data collection and accountability for funding, and increasing prevention measures targeted at children and younger people to stop them from falling into addiction in the first place.

Marshall, who held a fundraiser at his home for Brown ahead of the 2018 election, says the Governor “promptly ignored” the findings.

“I genuinely believe that people are dead today because (of ) Kate Brown’s criminal neglect. She could have saved lives,” Marshall said.

While Marshall is more poignant in his criticism, Vezina says he understands Brown had a focus on COVID, though one thing he’d like to see are the metrics around addiction, substance abuse and treatment studied as vigorously and reported as publicly as the pandemic’s case count and transmission.

“I got an email telling me every day how many presumptive cases, how many hospitalizations, how many hospital beds are available … We do not have anything like that in Oregon. We have a tricycle with flat tires just to get around,” Vezina said.

In a response to the criticism, Brown’s spokesperson Charles Boyle pointed to investments made in the state legislature, such as $350 million in 2021 for grants and workforce development as well as $121 million in Oregon Health Authority’s budget to fund existing behavioral health centers and $700 million for affordable housing development and permanent supportive housing. Boyle pointed to meetings with groups like Marshall’s Oregon Recovers about the next steps.

“Oregon is in the middle of a transformation. We no longer criminalize Substance Use Disorder and have committed more than $300 million in new funding to providers forming Behavioral Health Resource Networks through the Measure 110 oversight and accountability council,” Boyle said in a statement.

The move from criminal-justice-based intervention to treatment-based care, Vezina believes is a worthy one, though he acknowledges the fickle space Oregon is in right now with a more permissive environment without the services in place to respond to people who fall victim to addiction.

“The transition from expecting cops to deal with addiction to health care is going to take a little bit of time. The money going into recovery from Measure 110 is critically important…it’s effective but it’s going to take time,” he said.