PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — On May 18, 1980 at 8:32 a.m. the Pacific Northwest changed in a instant. The entire north face of Mount St. Helens slid away, creating the largest landslide ever recorded.

The violent eruption killed 57 people, destroyed more than 250 homes and sent people in the Toutle River valley running for their lives.

“I was living in Australia and I can remember where I was when Mount St. Helens exploded,” Oregon State University geologist Adam Kent said.

Kent ended up moving to the northwest to study volcanoes.

“It was the start of the realization that America has significant volcanic hazards and really they need to be understood,” Kent said.

He said on this 38th anniversary, when Hawaii’s largest volcano just happens to be spewing lava and gas, it’s important to recognize the Cascade volcanoes have no connection to what’s happening there.

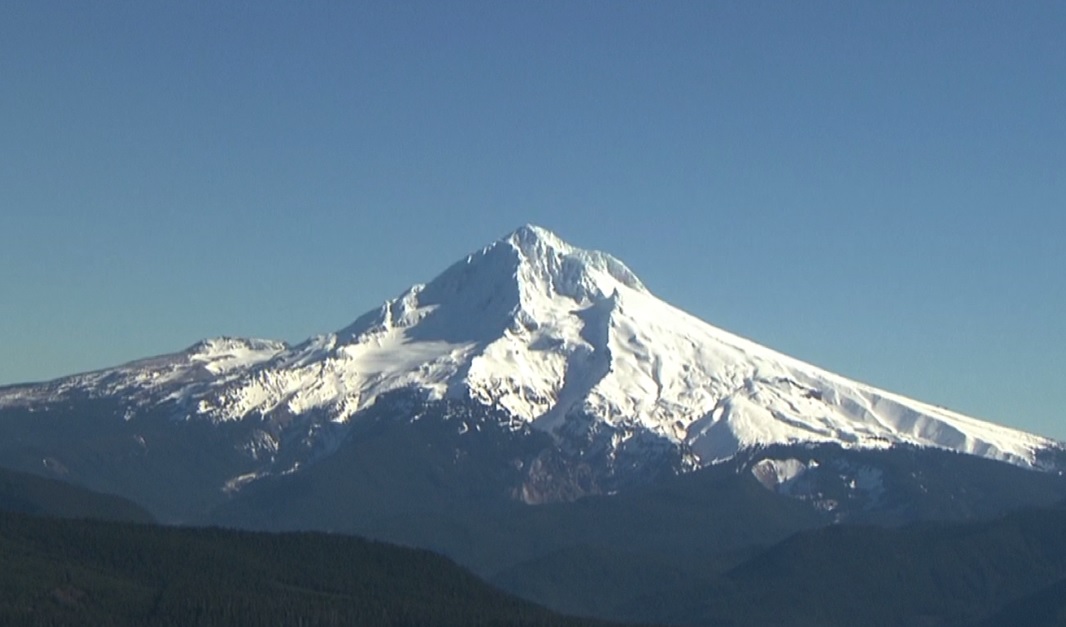

Even so, we are surrounded by active volcanoes, including Mt. Hood, which last erupted in the 1780s.

“Lewis and Clark didn’t see the eruption, but they recorded some effects on local rivers, the Sandy River in particular,” Kent said.

Scientists say Mt. Hood, Mount St. Helens and several other Cascade volcanoes still have the potential to erupt in the foreseeable future.

Mount St. Helens has forever etched in our minds the hazards associated with living near volcanoes. Scientists say understanding those hazards will be key to staying alive the next time a local volcano heats up.

Thanks to research and technological advances following the Mount St. Helens eruption, there is plenty of information to help people prepare for another event. The U.S. Geological Survey’s volcano website can tell you a lot, for instance, if you live along the Sandy River, it would take about 3 hours for a major mud flow, or lahar, to rush down Mt. Hood to where the Sandy meets the Columbia River.