Editor’s note: This is part three in a series looking at how the pandemic has impacted women in the economy and workforce. Read part 1 | Read part 2

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — In Oregon, as vaccine distribution increases and parents who left their jobs are itching to get back to work, many are realizing the state’s already insufficient child care options have further diminished during the pandemic.

From April 2019 to April 2021, Oregon saw about a 15% decrease in the number of child care facilities throughout the state. The number of care facilities dropped by more than 500 between April 2020 and April 2021.

Even before the pandemic, all 36 counties in the state were considered child care “deserts” for children ages 2 and under, according to a report from Oregon State University. That means there are at least three children under the age of 2 for every available child care slot in the county. Twenty-five other counties qualified as child care deserts for children ages 3-5.

State officials say COVID-19 restrictions, low wages, fear of contracting the virus, and the inability to keep up with costs are a few of the reasons the number of child care providers decreased over the past year.

“It was a difficult industry with high turnover, about 30%, pre COVID. And then I think, you know, the pandemic has just exacerbated that,” said Alyssa Chatterjee, acting director of Oregon’s Early Learning Division.

While hundreds of care facilities have closed their doors during the pandemic, Maria Medeiros, owner of Casa Feliz Child Care in Portland, has kept her two locations open, but the pandemic has hurt her business.

Even though Medeiros decided to stay open and registered as an emergency child care provider with the state, she said many families felt it was safer to keep their kids at home. She said the families who pulled their kids out paid half their normal wages. Medeiros had to lay off some of her employees.

In Mach 2020, as part of Oregon Gov. Kate Brown’s executive order, all child care providers were ordered to close unless they were providing emergency child care. Child care facilities could complete an application to provide emergency care. That would allow them to care for 10 or fewer children at a time in a classroom or home. They were also required to prioritize children of essential workers and follow certain safety protocols outlined by the Oregon Health Authority.

For some providers, this meant they saw a significant drop in the number of children they were caring for, and a significant drop in the revenue they were generating.

“A room that used to have 20 kids was running with two kids. You know, it’s very hard to keep the lights on in that sort of situation,” explained Ren Johns. She owns PDX Waitlist which helps child care providers manage their waitlist and also helps parents with the application process. She said she saw how providers began struggling early on.

According to a survey published in April by Portland State University, the Oregon Department of Education’s Early Learning Division, and OLSC Developments, Inc., 60% of Oregon families experienced a disruption in child care due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

KinderCare Learning Centers, a Portland-based company with locations across the country, closed approximately 1,100 of its 1,500 locations when the pandemic began, said Michelle Mazzulo, the regional vice president of KinderCare in the Northwest. Since then, all locations have reopened and Mazzulo said most are at capacity.

When Mazzulo spoke to KOIN 6 News on May 17, 2021, she said the state regulations in place were still limiting the number of families they could provide care for.

“If we could open the last of our classrooms, we’ll be able to help our communities better,” Mazzulo said.

Mazzulo said until the state allows centers to return to pre-COVID capacity, KinderCare can only hire lead teachers, not assistant teachers. KinderCare said assistant teachers are not allowed to work alone and the current state guidelines require a 1 to 10 staff to child ratio. Without assistant teachers, Mazzulo said their staffing has been stretched thin. If a lead teacher is unable to work due to vacation or illness, they have to close the classroom.

Medeiros from Casa Feliz is also facing her own staffing struggles. She said rehiring people has been the greatest challenge for her during the pandemic. She said she’ll post an advertisement for a job and will schedule interviews with about a dozen people, but none of them will show up.

She suspects some of them are earning more money through expanded unemployment benefits than they would earn working for her.

Chatterjee from the Early Learning Division said that very well could be the case.

“It’s not that these unemployment benefits are too good. It’s that they’re not making you’re not making a living wage in your previous roles,” she said.

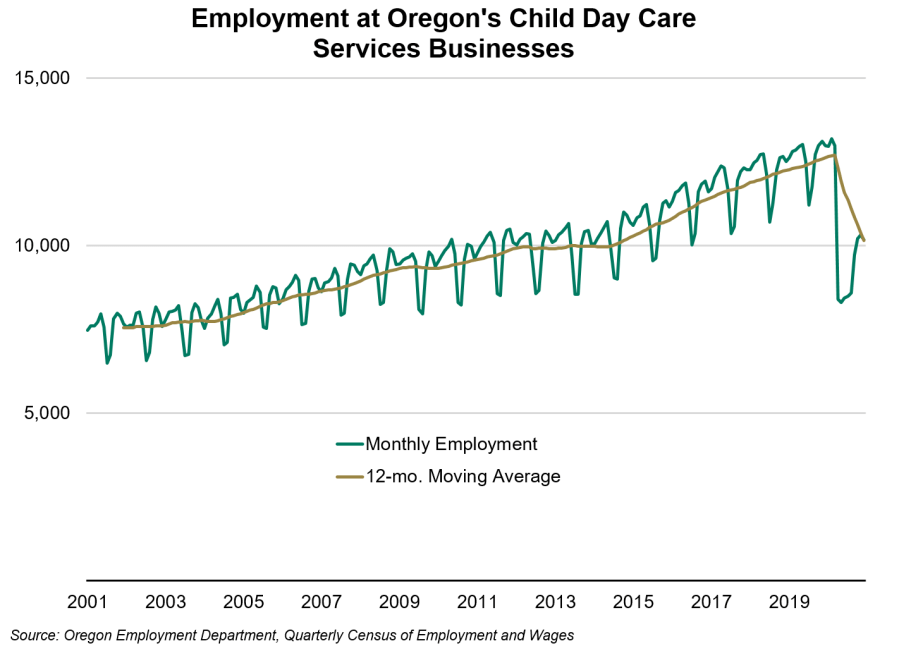

According to the Oregon Employment Department, employment in the state’s child care industry dropped 35% from March 2020 to April 2020. By December 2020, the industry had only regained less than 40% of those losses.

That’s part of the reason why many state lawmakers are on a mission to support the fragile child care industry.

Rep. Karin Power is head of the Oregon House Committee on Early Childhood. She knows that even before the pandemic, all counties in Oregon were considered child care “deserts” for infants and toddlers, meaning that there are at least three children under the age of two for every child care slot in the county.

During the pandemic, she’s sponsored legislation such as House Bill 3073, which would change the Early Learning Division to the Department of Early Learning and Care and would establish the department as a state agency that’s separate from the Department of Education.

If passed, the bill would allow Employment Related Day Care subsidy payments to be made to child care providers based on enrollment rather than attendance, which Chatterjee said would provide a more stable income for providers, even if children are absent. It would also allow a sliding scale subsidy option for families, depending on their income.

Power is also sponsoring House Bill 2503, which would expand eligibility for certain child care subsidy programs. It would transfer rule making authority to the Early Learning Council, something that would be formed if House Bill 3073 passes.

“This year, the child care crisis came to our attention because it stopped working for all families, but it had never worked well, especially for parents who work multiple jobs, single parents, and other people who don’t usually have a seat at policy making tables,” Power said.

She’s also advocating for House Bill 2819, which would extend the earned income child tax credit to those who qualify and who have a taxpayer identification number. Currently, it’s only available to people with a social security number. Proponents say the bill would allow Oregon’s immigrant families access to the tax credit.

In March 2021, Gov. Kate Brown urged state lawmakers to support a $250 million summer learning and child care package to help students get back on track after more than a year of social isolation and restricted schooling in many places.

In the U.S. Senate on May 26, Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., introduced a new bill that would allocate mandatory funding to build child care availability.

“It’s past time the federal government treat child care as the critical infrastructure it is and build a system that doesn’t leave families behind. Every family deserves access to affordable, high-quality child care,” Wyden said in a statement.

President Joe Biden himself is prioritizing child care in his proposed American Families Plan, which promises to ensure lower- and middle-class families would spend no more than 7% of their income on child care. His American Jobs Plan asks congress to provide $25 billion to modernize child care facilities and increase child care in areas that need it most.

Biden’s American Rescue Plan released $39 billion on April 15 to child care providers to provide support to families as the pandemic drags on.

Chatterjee said the state has been distributing this money to providers through grants. She said issuing grants is likely the best short-term solution to keep child care facilities afloat.

“Through these sort of one-time funds, we may be able to buy us enough time to then build in some of the back end to make sure that they’re successful,” she said.

On a smaller level, lobbyists in Washington County have been pushing for a tax-funded program that would support child care providers.

Katie Riley is the president of Washington County Kids and Susan Bender Phelps is the president of Friends of Washington County Kids, a political action committee dedicated to pushing for tax-funded child care support. For more than 10 years, the two women have been advocating for a tax levy to expand out-of-school time services.

The women said county commissioners voted against putting the initiative on the ballot in 2020, but they’re hoping 2021 will be the year it moves forward. They said they’re redrafting the proposal to be funded instead by a high-earner income tax, like Multnomah County’s Preschool For All initiative, which passed in 2019.

“There would be a system set up where county staff would assess needs. There would be an oversight committee that would decide on priorities,” Riley said. “We want to provide encouragement and training that will help providers improve their quality.”

The two women want funding for all school-aged child care, not just for early learning. They said they have strong support from the community now and believe the pandemic has opened people’s eyes to the need for better child care.

For now, Chatterjee said the best resource to help care facilities during the pandemic is grant money. Medeiros said grant money has really helped her during 2021 and Chatterjee said the state is about to roll out another phase of grants to help providers reopen.

“That’s going to be, I think, the biggest carrot that we have to reopen our former supply and recruit additional folks into the childcare workforce,” she said.

While 2020 and 2021 have been challenging years for Medeiros’ business, she said there has been a silver lining. She said the pandemic has really changed the way parents treat care providers.

“This is more than just a job, you know? This is so important. We spend more time with their child than themselves sometimes,” she said. “I always felt respected, but I can tell that even more now, [parents are] appreciating and understanding our job.”

Are you a parent currently looking for child care?

For parents who are desperate for care right now, Johns from PDX Waitlist has advice. She suggests they get creative and consider nannies or a care swap with another family or ask extended family members to visit and help provide care. She also said families should avoid day care waitlists if they don’t have time to wait.

Chatterjee also suggests parents call 211 for free, customized referrals to child care providers in Oregon.