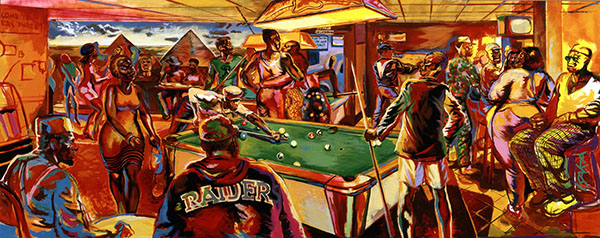

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Isaka Shamsud-Din has spent a lifetime using art to celebrate the beauty and excellence of Africans and African Americans in a way that he never saw represented in books and movies growing up.

“I got a pride. I had to earn that pride by studying on my own, by digging. That’s why so many African Americans and so many Africans, we’re not linked. We don’t feel the spiritual link because we don’t know each other,” said Shamsud-Din, who is 79.

He’s the man behind many iconic pieces of public art in Portland, including a mural of Martin Luther King Jr. from 1989 in Northeast Portland called “Now is the Time, the Time is Now.”

Shamsud-Din also painted a mural honoring African American pioneers in 1983 which now hangs in the Oregon Convention Center, called “Bilalian Odyssey.” North Portland’s Dawson Park also has his work installed as part of a 2017 renovation and multiple McMenamins restaurant locations hang his framed paintings on their walls. In addition, Portland Art Museum is currently holding an exhibit of some of his work, named after a portrait of his father, called “Rock of Ages.”

Originally from Texas, the artist and activist moved to Oregon in 1947 when he was just a child.

Shamsud-Din’s father, who was a hard-working farmer, was once dragged from his home in the middle of the night by a mob in Texas.

“I didn’t know for a lot of years, it was like a dream. We were hiding under the beds. We had no electricity. We were living good but we were living in another time.”

Shamsud-Din found out later from speaking with his father that he’d been assaulted because he used the front door, instead of the backdoor, when he dropped off the rent to his landlord.

“His crime was that he refused to submit,” he said.

The mob had beaten Shamsud-Din’s father and left him for dead, tied to a tree. He survived, unbeknownst to his attackers.

To escape the racism of the south, Shamsud-Din’s father moved himself and his family to Vanport, Oregon, after he secured a job in construction.

“Within six months he was able to work hard enough, diligently enough…to bring all of us, 10 children and his wife, to Oregon.”

Vanport represented Portland’s first experiment with an integrated community, where black and white people went to school, rode the bus, and ate in restaurants side-by-side. It was a culturally diverse historic city used for wartime public housing and located in modern North Portland. The city greatly increased the black population of Portland, many of whom moved there from other states to work on the shipyards during World War II.

Less than a year after Shamsud-Din’s family moved there, however, Vanport was flooded on Memorial Day 1948 and their new home was decimated. Fifteen people were killed and 18,500 were displaced, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Shamsud-Din was just 7 when the flood hit around 4 p.m. that day.

“We could see the water was rushing down the street within an hour …less than that. The only thing we were able to save was a little white radio,” he said.

The flood occurred because extra rainfall and snowmelt swelled the Columbia River days before and a railroad berm holding back the water from the town failed.

Historical records indicate that the Portland Housing Authority issued this statement the morning of the flood: “Remember: Dikes are safe at present. You will be warned if necessary. You will have time to leave. Don’t get excited.”

“They slipped a note under our door that same day saying ‘do not panic,'” Shamsud-Din recalled.

After the flood, the family moved to Ohio for a short period and then returned to Portland.

It was in second grade that Shamsud-Din first self-identified as an artist. He was tasked with doing illustrations on glass slides to coincide with a class book they were reading, whose characters were all white.

“I was drawing, I just had the need to draw and challenge myself. I’d doubt that I could do this and then eventually get up the nerve to try,” the artist remembered.

Shamsud-Din’s interest in drawing occurred during what he called an “oppressive” school environment. Few if any teachers or administrators were black because for a long time they weren’t allowed to be hired in Portland, even at a majority black school like his Jefferson High School. The curriculum and culture offered “no solid, positive image of ourselves,” he said.

The lack of representation Shamsud-Din observed became a motivation for his art.

“The beauty. When I started concentrating on doing drawings and painting African Americans was right at the beginning of my teenage years,” he explained.

Shamsud-Din’s talent soon became obvious when he won two scholarships for art back to back. The first was for a local admission to a weekly Saturday children’s art class at Portland Art Museum when he was 13. By age 14, he’d won a prestigious nationwide scholarship studying art at the University of Kansas, where he studied over three summers in high school.

He was the youngest of just four Oregonians to receive the prize.

Shamsud-Din then attended college for two years at Portland State University, but he left in the mid-1960s to work for the civil rights movement in the southern United States.

He would eventually finish his undergrad in anthropology and go on to receive a Master’s Degree in Fine Arts from Portland State University.

In his anthropological studies, the artist researched the cultures of African people, which he said informs his art.

“I have as my first audience African people and African American people,” Shamsud-Din said. “I want my work to be a testament that they can share things about ourselves that they may not think of or that’s not being represented by anyone.”

Shamsud-Din spent over 40 years teaching art and black studies at various institutions around Portland–including at public schools, PSU and Pacific Northwest College of Art–retiring in 2006.

He was also one of the artists behind what was then the state’s largest mural project at the time, the Albina Mural Project. It hung from 1978 until 1983 on the exterior walls of the Albina Human Resource Center in the heart of North Portland’s Albina neighborhood and depicts key transition periods of African American history in the northwest and abroad. It was removed by the artists due to deterioration from rain, PSU’s website stated, where a documentary film of the project can also be found.

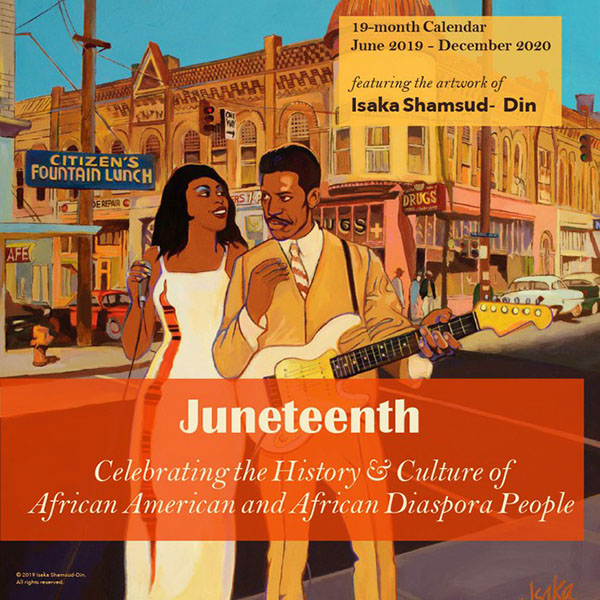

On June 19, 2019–a holiday known as Juneteenth in which many African Americans across the country celebrate emancipation–Shamsud-Din was honored by Portland City Hall proclaiming it “Isaka Shamsud-Din Day.”

A 19-month Juneteenth Calendar that reproduces many of Shamsud-Din’s paintings is currently available through his website. The 2019-2020 calendar was made possible with sponsors from local art patron and philanthropist Arlene Schnitzer, Teressa Raiford of the social justice group Don’t Shoot Portland and two PNCA professors, Victor Maldonado and Matt Letzelter, among others.