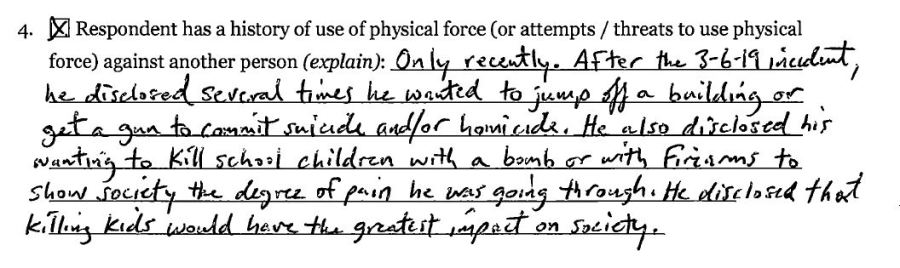

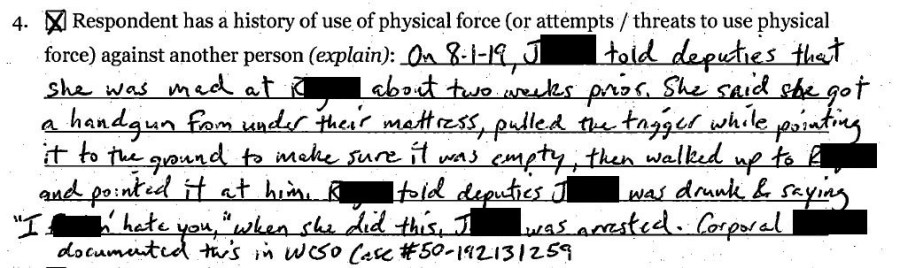

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — In September 2019, a Beaverton police officer filed an extreme risk protection order against a man after a series of disturbing incidents. According to court documents, it started when the man, a concealed-carry holder and a veteran, went to his doctor, and then asked if they allowed concealed carry. The answer was no, so “he pulled a handgun out of his pants, unloaded it & set it on the counter. He then took it out to his car. He told police that he was ‘high’ at the time.”

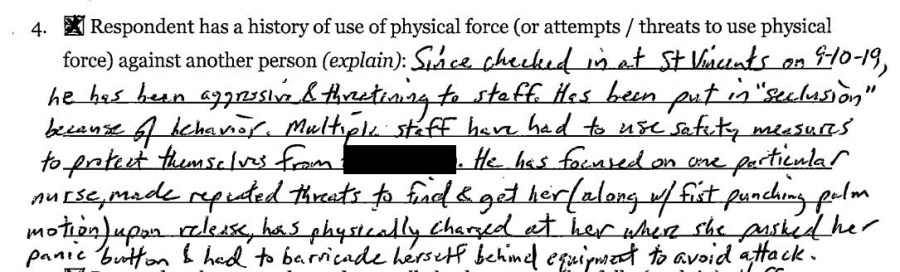

The man ended up getting checked into St. Vincent where the officer wrote that he was “aggressive & threatening to staff,” including charging at one nurse who “pushed her panic button & had to barricade herself behind equipment to avoid attack,” according to the documents. The judge signed the order, removing his right to possess firearms for one year.

It’s one of dozens of cases this year in which Oregonians have lost their right to keep and bear arms through the power of the state’s red flag law.

Background

“It is my hope that all Oregonians know about these laws so we can get guns and other weapons away from people who shouldn’t have them.”

Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum

Connecticut was the first state to enact a version of a red flag law in 1999, after a shooting at a state lottery office. Now more than a dozen states have instituted similar legislation. Oregon and Washington are among the early adopters of extreme risk protection orders (ERPO), supported by anti-gun groups and high-profile politicians, including Oregon’s Attorney General, as an important tool to get guns out of the hands of the “wrong” people.

Oregon’s bill passed the state legislature by a narrow margin in 2017 and went into effect in January 2018 with 74 ERPOs filed during the first year. According to the anti-gun organization Everytown, Washington had 120 that year. This year, Oregon’s numbers have already risen. Through October, 96 ERPOs had been filed statewide. KOIN 6 analyzed state data from the earlier part of the year to see where the orders were being filed, by whom, and what the outcome was.

“The most important thing is for people to feel safe”

A family member or anyone living in the same household as the subject can file an ERPO. Law enforcement may also file it, and do so in the greatest numbers according to state data. Washington County Senior Deputy District Attorney Gina Skinner said concerned family members who want to remain anonymous can also ask police to file the ERPO.

“The most important thing is for people to feel safe and to make sure people don’t harm themselves with firearms,” Skinner said.

The petitioner has to demonstrate that the subject presents a risk of suicide and/or causing physical injury to another person in the immediate or near future.

Then, the court holds a hearing, usually within 24 hours. At this point, the person being issued the order (AKA the respondent) still might not know what’s happening. If the judge finds “clear and convincing evidence” of danger, the respondent gets served with the order and must surrender all weapons and concealed handgun permits within 24 hours.

Criminal defense attorney Michael Romano sees many potential flaws in the system.

“One of the biggest concerns is that you could be sitting at work or at your house minding your own business and all of a sudden you get served with an order that says surrender all your firearms … and you didn’t even know that that was taking place and didn’t have an opportunity to be heard,” Romano said.

The 24-hour timeline can also be a substantial burden, Romano said. Since you aren’t allowed to have a friend or neighbor look after your gun collection while you sort out your legal issues, many people have to quickly find a gun dealer who can handle the transfer of firearms. That means paying a $10 background check fee for each gun, and a separate transfer fee.

“For people with a large collection, that’s going to cost quite a bit of money,” he said.

Something else that will cost a lot of money: a lawyer. Unlike with other crimes or civil statutes, Oregon’s red flag law does not give respondents the right to an attorney.

“So if you are of modest means and you have one of these filed against you, whether it has merit or it’s completely bogus, you have to go out and hire your own attorney or figure out how to do it yourself,” Romano said.

He also worries about the potential for abuse, particularly in custody disputes or other domestic conflicts, and “strange” risk factors listed in the statute. For example, one factor for the court to consider is whether the respondent bought a firearm within the last six months. There’s also a box to check if the respondent has ever been convicted of DUII.

“I don’t know of anybody who’s sort of drawn a connection between people who get DUIs suddenly become mass shooters or commit suicide,” Romano said. “They don’t.”

Skinner is less concerned about numerous people abusing the statute, noting that if the petitioner acts “with malice,” they could face criminal liability.

“So there is a backstop for someone if, for whatever reason, they felt that they wanted to do it and it was not based on any truth and you could show that they were doing it for inappropriate reasons,” she said. “But so far, because the numbers are so small, that really hasn’t been borne out to be occurring.”

Skinner also doubts that Oregon will see a significant increase in the number of people filing ERPOs since they are used in “relatively limited” circumstances, and other laws may also have similar outcomes. For example, Skinner said one new law makes it so anyone with a restraining order against them will not be allowed to have firearms.

The trouble with enforcement

Skinner said it’s up to each county to decide how to enforce the law. In Washington County, she said respondents have to file a declaration that they have turned over their weapons. If they fail to do so, the sheriff’s office investigates.

“Oftentimes they’re people who have some severe mental health issues, or maybe didn’t understand what was served upon them,” Skinner said. “And the sheriff’s office has done a really good job so far with working with those people.”

If the subject intentionally ignored the order, the DA’s office could file contempt charges.

It gets more complicated if the subject lies to the court about having weapons. Right now, Skinner said, it’s difficult for law enforcement to prove otherwise without searching the subject’s home. For that, they would need a warrant.

“So that’s a pretty lengthy process to be able to actually go inside and enforce the order,” Skinner said.

In Maryland, enforcement of one 2018 ERPO turned deadly. Police shot and killed a man who struggled with officers over his gun when they demanded he turn it over.

Romano notes that gun owners tend to be “passionate people” who are likely to be angered if police show up out of the blue and demand they surrender their entire firearms collection. But he stresses that respondents should “stay calm and comply with the order.”

“Even if they fundamentally disagree,” he said. “This is not something that’s worth putting yourself or someone else at risk.”

“The writing’s on the wall”

Romano isn’t sure why there’s such a focus on red flag laws when Oregon already has a civil commitment statute, in which somebody deemed to be a threat to themselves or others can be held for up to five days before a hearing. They can also be compelled to seek treatment as an outpatient or be taken into custody for involuntary care.

In the instance of ERPOs, Romano said the respondent may lose their firearms but are not otherwise stopped from harming themselves or others.

“So with the civil commitment statute, you arguably got more protections in place not only for the community, but you have greater due process protections in place for the accused,” Romano said. Those due process protections include the right to an attorney, even if you can’t afford one, a luxury those facing ERPOs don’t get.

“It’s not just tinfoil hats,” Romano said. “I think there’s some people that are saying this law looks like it was passed by people who have a specific problem with firearms and gun owners as opposed to trying to protect the community.”

Despite his reservations about many parts of the statute, Romano predicts other states will continue adopting similar laws.

“I think the writing’s on the wall that people are … sick and tired of turning on the television … seeing mass shootings, and then more specifically hearing after the fact that a bunch of people … knew that there was something going on but didn’t do anything about it,” he said. “I think you’ll see more states pushing for legislation like this because they feel like there’s not enough being done to protect the community at this point.”

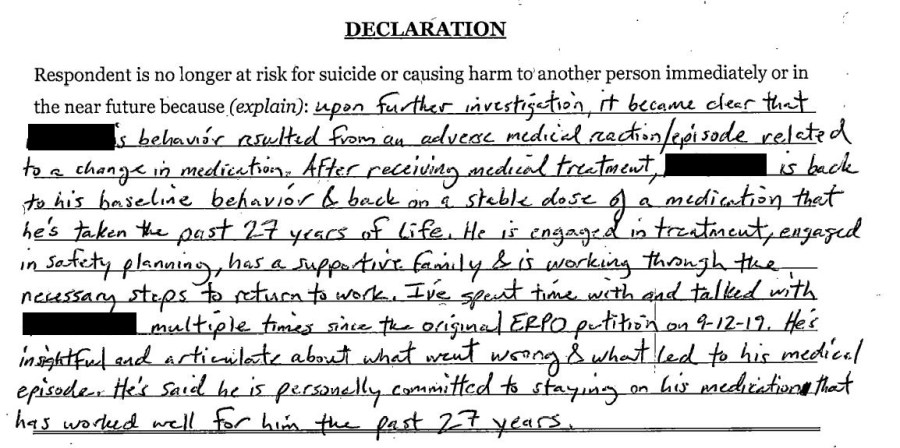

As for the man at the beginning of this story, things appear to have gotten better. On Oct. 3, 2019, the officer who filed the initial ERPO, filed a motion to terminate the order. Dismissing ERPOs after the fact is rare: It happened only once this year in Washington County, according to the documents.

The officer wrote that it became clear the man’s “behavior resulted from an adverse medical reaction/episode related to a change in medication.” The man got back “on a stable dose of a medication that he’s taken the past 27 years of life.” The officer wrote that the respondent was engaged in treatment, has a supportive family, and is “insightful and articulate about what went wrong.”

KOIN 6 did reach out to the man, but he declined to comment on his experience.