PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Teri Anderson and Marla Knauss don’t know each other. But these Portland mothers were living parallel lives as their sons were overtaken by mental illness.

Each tried for more than a decade to get mental health treatment for their sons. But each failed. Now they’re talking with KOIN 6 News to provide a perspective on how the intersection of mental illness, addiction and homelessness has hit a breaking point in Oregon.

Oregon laws have long made it difficult to force people to get mental health treatment. Residents now regularly witness people in public in a mental crisis.

Oregon law allows a person to be treated for a mental illness against their will if they are experiencing an emotional disturbance and are imminently dangerous to themselves or others.

In case law, the Oregon Court of Appeals has narrowed what the terms “danger to self” and “danger to others” mean, making it a very high bar to reach.

“I am up against the state of Oregon, literally,” Knauss said. “The way we are dealing with it is as crazy as my son.”

“As a mom,” Anderson said, “I’m thinking they have parents that love them and they can’t get help.”

Joshua and Max

Teri Anderson adopted her son Joshua at birth.

“He was the most curious, beautiful baby,” she said. “But I knew something was up from the minute they handed him to me from the birth mother.”

By the time Joshua was 7, he was diagnosed with autism at OHSU. They began specialized therapy, but by the time he was 13 the behavior worsened.

“My sweet little genuine, beautiful boy would have these fits and pull hair out and fight and come after me. And we would both end up in the hospital several times. We ended up in the hospital from these rages just out of nowhere,” Teri said.

At that time she was still under the impression these outburst were due to autism. Teri and her husband did their best to get Joshua through high school and into the Job Corps.

“How he was so beautifully gifted. But there was this other side,” Teri said. “I saw my son cloaked in these black feathers of mental illness, but the little sweet boy was still in there when he wasn’t in a state of psychosis.”

Across town, Marla Knauss gave birth to her only child, Max.

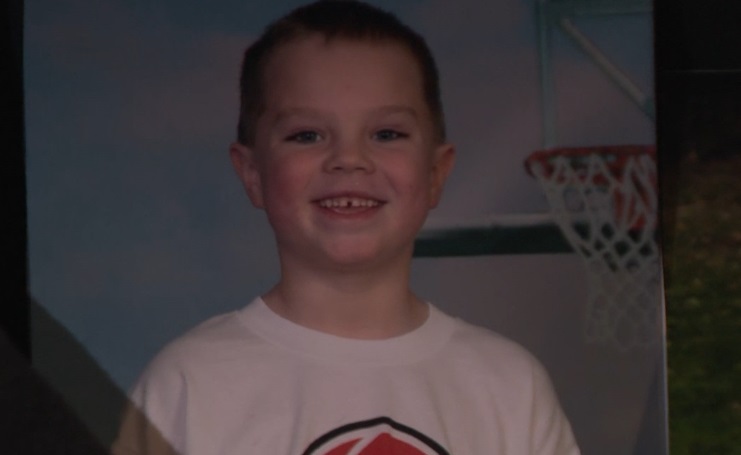

“Seeing those pictures of my son just reminded me of how much he was wanted and really loved,” Marla said.

As a kid, Max was a natural athlete, just like his mom. Marla got him involved in numerous sports.

“It was just the most fun time of my life,” she said.

Until it wasn’t. In high school, Max began to struggle. His mental health declined, first depression, then paranoia.

“The illness is progressive,” Marla said. “No way did I see this coming. And when it happens it is a hard left turn.”

This hard left turn also happened to Teri’s son, Joshua. The worsening schizophrenia led to the first time her son had to sleep on the streets.

“The police removed him from the house one night when he had tried to kill us,” Teri said. “I made sure he had his phone. I was freaking out. I called him the next day and said, ‘Joshua, you can come home, but you have to go to therapy. You have to take your meds.’ (He said,) ‘Oh, Mom, I love it here.'”

Two options, neither good

By the time Joshua and Max had turned 18, the paranoid schizophrenia took over their minds. Their parents lost custody of their mentally ill “adult” children.

Teri Anderson and Marla Knauss faced two options.

First, they could try an extremely labor intensive battle of guardianship with attorney fees rising quickly into the thousands of dollars. Their second option would be to get a judge to civilly commit their sons to the Oregon State Hospital for treatment. That is also often unattainable.

“We actually have a place in the back of our house where he could have lived. We could have gotten him an apartment, private treatment. We could have done anything,” Teri said. “Portland refused to allow me to have guardianship over my son.”

In 1993, the Oregon legislature passed laws outlining specific rights of people receiving mental health care. In the ‘least restrictive way’ they allowed the mentally ill the choice to participate as much as possible in all decisions that affect them.

The way the state laws are written, it was up to Joshua to decide if he wanted help.

“I would have to tell him I had this special app on my phone that I could scan the doctors and the nurses to make sure they didn’t belong to ISIS, that they weren’t the Illuminati, that they didn’t belong to Bilderberg. Hello? Does that sound like a kid that is capable of making his own decisions?” Teri asked, rhetorically.

As the years passed, both Joshua and Max would spend some time at home. Inevitably, though, they returned to the streets. They became addicted to hard drugs and cycled through the various systems.

“When he was about 20 to 23, his mental health was declining and we would get into the hospitals and I would ask for a psych eval and would be told, ‘We don’t want to take his rights away,'” Teri said. “You don’t take his rights away. He’s clearly psychotic. He cannot make decisions on his own. Cognitively, he’s 13 years old. Are you going to call the parents of whomever he may harm and tell them because you didn’t want to take his rights away they no longer have a child? That was my greatest fear.”

However, it was up to Joshua to ask for a psych evaluation. To force someone into treatment in Oregon, the law states they must be in imminent danger of killing themselves or harming someone else. Without legal guardianship of their adult sons or an involuntary civil commitment order from a judge, even forcing Joshua or Max to go home would be against the law.

“It’s impossible. I asked for that for 10 years. I was never allowed to help my son. I was told I would be arrested if I did. It was kidnapping,” Teri said.

The streets

The last time Teri Anderson saw her son Joshua was in August 2021.

“He was covered with feces. I thought he was spilling water, but he wasn’t. He just was urinating. He was filthy. He wasn’t there. He was just a shell,” Teri said.

“And on the way home, I just thought Portland is not only denying him the right to be treated, they’re letting him die a cruel and inhumane death. On the way home, I just prayed ‘God take him.’”

After a decade of begging for help and fighting for custody, God answered Teri’s prayer.

“We found out he had been lying in front of the Salvation Army for 40 hours with employees walking over him,” she told KOIN 6 News.

Joshua died of a drug overdose outside a doorway in downtown Portland. He was 28.

While she was relieved he’d no longer be at risk of harming others or have to sleep through another torturous night on the streets, Teri Anderson can’t help but imagine a life he could have lived — if only involuntary commitment and community treatments for the mentally ill weren’t out of reach.

“My son was extremely dangerous. He was red flagged from every shelter. He needed to be put somewhere where he couldn’t hurt someone, where he could be medicated.”

Marla Knauss also tried paying for an apartment for her son, but lost thousands of dollars in the process.

“He’s not well enough. Even with the medication he really has to be supervised. He can’t go shopping. He can’t drive. He can’t do his laundry. He even has to be coaxed into bathing and brushing his teeth. Cooking is risky,” Marla said.

She also could not get her son civilly committed. But she did get a restraining order against him to purposely get him arrested — for the safety of everyone.

“I’ve had to resort to the justice system to get help. Why does it have to get this far?” Marla said through tears. “We all see people with mental illness on the street. They all have caring parents. Every one of them had parents that tried. When I’m faced with the last resort where he can’t live with me because he’s combative and gets upset and then takes it out on me. I can’t live with that. Or he’s outside because there’s nowhere to put him, literally.

“And what does it say about us as a society when the most vulnerable are literally left to die? And we have become so desensitized that we can just step over them?”

Max is currently in jail after assaulting Marla and beating her in their home. He sits a prisoner in his body and his mentally ill mind.

But Marla said it shouldn’t have to be this way.

“The life of my son is worth something to me,” she said. But she is left with no hope that her only son will survive this living hell.

Teri Anderson and Marla Knauss are advocates for early intervention — more psychiatrists and lifelong facilities to care for people like Joshua and Max who have severe and persistent mental illness.

More than anything, they want to witness change.