PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — When the pandemic first impacted Oregon, Mary Sarhadi lost her job almost immediately.

Sarhadi, a mother of two young girls, was working as a preschool teacher in Northeast Portland. When state rules limited the number of children allowed at day care centers, Sarhadi was laid off. She also lost child care for her youngest daughter, who attended the preschool.

Now, 14 months later, she’s still without a job.

“It’s been hard, definitely working off our tax returns, saving what we can, using what we need and not just splurging,” she said. “We have to manage what we do, where we go, what we buy.”

When COVID-19 initially caused shutdowns across much of the United States, women’s jobs were disproportionately impacted compared to men’s.

In March 2020, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics said the unemployment rate was 4.1% for men 20 and older and 4% for women. In April, the rate jumped to 13.1% for men and 15.5% for women. By April 2021, the unemployment rates for men and women were back to being close to one another; men had a 6.1% unemployment rate and women had a 5.6% rate.

The initial plunge in women’s unemployment and the massive number of women who have left the workforce over the last 14 months have some experts reportedly saying the current economic recession is more like a “shecession.”

According to the Pew Research Center, from February 2020 to February 2021, a net 2.4 million women and 1.8 million men left the labor force, which means they aren’t working and aren’t actively looking for work.

Oregon, like all other states, saw its fair share of job losses. Some of the hardest-hit industries were those where the majority of jobs are held by women, including the leisure and hospitality industry, education, and “other services,” which include barbers, hairstylists, and tattoo artists.

“[The leisure and hospitality industry] lost almost 110,000 jobs in two months. That’s half its employment. So, one out of two jobs, just gone. And that industry does have a majority of women,” said Gail Krummenauer, a state employment economist at the Oregon Employment Department.

She published a report in January 2021 highlighting job losses in female-dominated sectors. Of these severely impacted sectors, most have not fully recovered. Krummenauer pointed out that while many educators have been able to work remotely, bus drivers’, cafeteria workers’, and custodians’ jobs have remained idle.

Josh Lehner, an economist with the state of Oregon, has been digging deeper into what’s preventing women from re-entering the workforce.

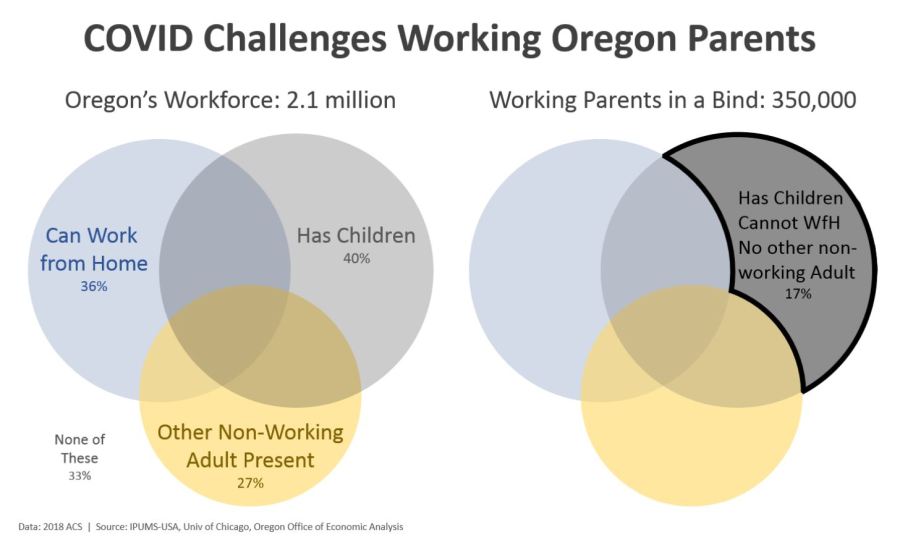

His research shows that 17% of working Oregonians check the following boxes: they have kids; they work an occupation that cannot be done remotely; they do not have another non-working adult present in the household.

With schools closed and child care centers operating at limited capacities, those parents had to make tough decisions.

“They’re really in this bind where they have to choose between going into their job, if they kept it, versus taking care of the kids,” Lehner said. “It’s a pretty large chunk of our economy that faces that really terrible trade-off or choice. And so, who has borne the brunt of that? It looks to be moms.”

Lehner said it’s not just moms, dads have also had to make tough job decisions this year. However, in one of his reports, Lehner said data released in January 2021 showed that employment among mothers was down 4.6% and employment among fathers was down 2.9%.

In a two-parent household, determining who keeps their job and who leaves their job when someone is forced to care for the children could come down to things like wage, benefits, and whose job is considered essential.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2019 said in Oregon, women working full-time made about 81.6% of their male counterparts’ average weekly earnings. Which means oftentimes, the woman in the household is earning less money.

For Sarhadi, she said it wasn’t an option for her husband to quit his job when the pandemic began. She said he’s a frontline worker who works at a local hospital.

Jenny Han Mackie is another mom who’s gone the entire pandemic without a job. She and her husband moved from Los Angeles to Portland in late 2019. Han Mackie’s husband landed a job in Portland right away, but she planned to work on renovating their new house for a few months before applying for jobs.

Then, the pandemic hit and her two boys couldn’t go to school.

“I don’t imagine how people that are working and managing their kids in school are doing it. And especially for my kids, they got Zoom fatigue really fast,” Han Mackie said.

She decided to stay home and help her kids with comprehensive distance learning. Becoming a stay-at-home mom was a big adjustment for her. Before moving to Portland, she worked full-time at America Honda Motor Company for more than 20 years.

“The pandemic, if anything, has illuminated all the things we didn’t know that parenting would require of us. And I think when I worked, there was a lot of that aspect of parenting 24/7 that I never had to experience,” she said.

In December 2020, Han Mackie started applying for jobs again. For a while, her search was coming up empty, but finally she received an offer and accepted a position on May 17, 2021.

“If I had to summarize it all in one word, I would say what I’m hearing from moms across the board is that it’s been a struggle,” said Lee Ann Moyer, owner of Portland Mom Collective, a website that provides support and resources to Portland-area families.

Moyer also does freelance work and owns Make + Take Studio, a workshop and event space in North Portland. During the pandemic, while Make + Take Studio has remained closed, Moyer said she’s had to continue paying rent for the space with the income she makes from her other jobs.

“I’ve just sort of tried to tread water the whole time and I’ve been able to do that thanks to the other two businesses, but it’s pretty demoralizing to pay for rent where you can’t use a space,” she said.

Chrystal Davis is another mom having a difficult time keeping her business afloat. She owns Keep It Classy LLC and makes her own skin and hair products. Her plan was to really get the business off the ground in 2019 and 2020. She purchased a lot of the supplies she needed to make her products but due to the pandemic, she said she hasn’t had the opportunity to get the products in barber shops and salons like she’d intended.

For now, she’s sitting in a lot of debt.

She said she’s determined to keep the business running, but this year has been discouraging.

“I think once we can kind of figure out what this pandemic is about and what’s our next forward move… and people see how good my products work and what they do, I think it’s going to work. I have faith in that,” she said.

She said she filed for assistance in the first round of the Paycheck Protection Program loan, but her application was denied. She said she has another application in for the second round.

As a Black woman, Davis said she’s also faced racism during the pandemic. In fall 2020, she said she went to drop off an order to someone in Washington. When the customer realized Davis was a Black woman, they said they didn’t want the product anymore.

“They saw me and my son were standing there, friendly, have our gloves on,” Davis said, “They said, ‘We didn’t know it was a Black people that made it.’” She said they left the money and refused to take the product.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show the unemployment rate for Black women in the first quarter of 2021 was 9% for those 20 and over. That’s significantly higher than the rate for white women, 5.1%. In the first quarter of 2020, Black women had an unemployment rate of 5.4% compared to 3% for white women.

Demetria Hester, a Black rights activist in Portland, lost her job in February 2020, before the pandemic impacted the region. She said she’s applied for jobs over the last 15 months and has had offers, but refuses to accept a job that pays minimum wage. She said she has an associates degree in culinary arts and deserves to be paid more.

“When you do apply to culinary jobs, they still want to pay you that $13 an hour. They don’t want to pay you the $15 and that’s not even what I’m worth,” she said. “As Black women, we’re always low-balled.”

KOIN 6 News asked Hester if she would ever accept a lower paying job just to have some sort of employment. She said no.

If there’s any good news about the pandemic-related recession, it’s that economists expect the workforce to rebound quickly as the vaccine is distributed and more businesses reopen.

“I’d like to hope that over the next several months we can see a continuation of what we have seen… which is that more areas of the state have moved out of the extreme COVID-19 risk category and that has allowed more economic activity to open up,” Krummenauer said.

Until then, Sarhadi said she’ll continue functioning as a full-time stay-at-home parent for her kids. She said her youngest daughter starts pre-k in the fall and that might be the best time for her to step into a new position.

“It’s just finding that right opportunity, finding that right time, security, to where you know your kids are being cared for while you’re out trying to make an income to help run the family,” she said.