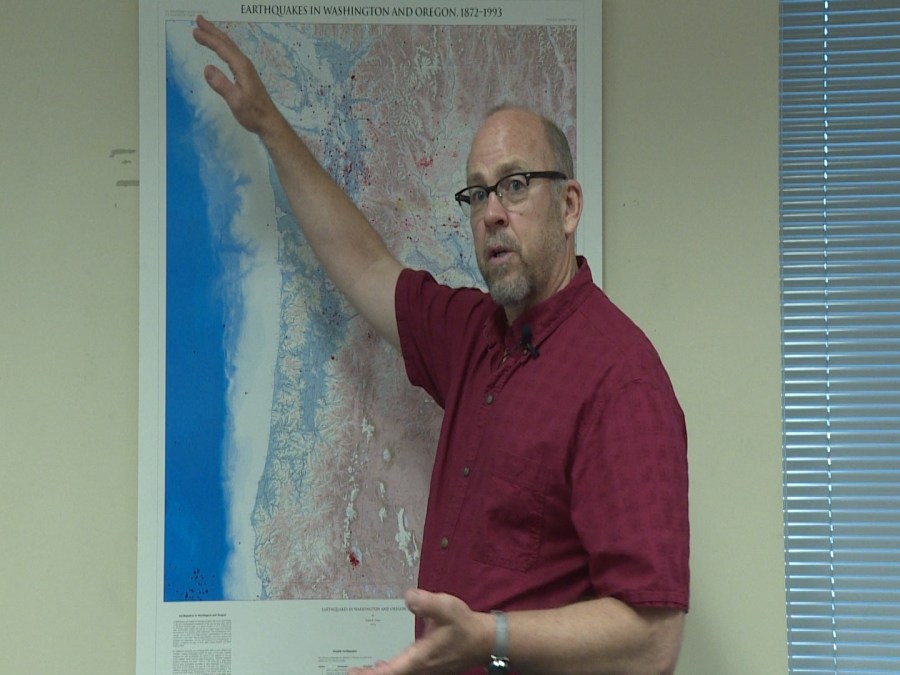

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — The Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake, often referred to as “The Big One,” will “affect the entire Pacific Northwest in one afternoon, and it’s going to change our economy and our culture and our society profoundly.” So says Ian Madin, senior scientist and earthquake hazard specialist with the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI).

More than four years after a New Yorker article brought unprecedented attention to the Cascadia Subduction Zone, scientists and emergency management experts are still trying to figure out precisely when it will happen, how bad it will be, and what we can do about it.

What is the Cascadia Subduction Zone?

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is a more than 600-mile fault located 70-100 miles off the West coast of North America. It runs from Cape Mendocino, California, all the way up to Vancouver Island, Canada. According to Madin, subduction zones begin when the earth’s plates pull apart, usually in the ocean. Volcanic eruptions form new ocean floor in those areas. When one side of the planet is spreading, something has to collide on the other side.

“That’s called a subduction zone,” Madin said. That zone produced the Cascade Range of volcanoes.

But the beautiful mountains come at a cost: subduction zone earthquakes are the strongest, “30 times bigger than the largest you can get on the San Andreas Fault,” Madin said.

Scientists have been able to learn Cascadia’s earthquake history for the past 10,000 years. It has had about 40 large earthquakes in that time, 19 of which have been magnitude 9 or larger and involved the entire fault.

The last time the world saw a magnitude 9 earthquake was in 2011 in Tohoku, Japan. Combined with the tsunami it triggered, that event killed about 20,000 people.

“That’s what we face here in the Pacific Northwest,” Madin said.

A report from the Oregon Office of Emergency Management predicts up to 25,000 fatalities from the earthquakes and following tsunami.

The last Cascadia event was in 1700. According to Madin, the average time between “Big Ones” is about 500 years, so we may still have some breathing room.

“(But) earthquakes are not like a bus. They do not arrive on a schedule,” he said. “Odds are somewhere between 12 and 20% in the next 50 years that we’ll see one of these magnitude 9 earthquakes … So it’s most likely that most of us living here won’t experience this earthquake based on those odds, but if we do it will be life-changing for everybody.”

“Life-changing for everybody”

Coastal communities will be hit the hardest because many lie in what’s called the tsunami inundation zone.

“In the tsunami inundation zone, everything is destroyed and the main priority is to get people out of there before it arrives so they aren’t killed,” Madin said.

Next, the coastal area that is outside the inundation zone, but still relatively close to the subduction zone.

“In that area, the damage is going to be widespread,” Madin said. “There won’t be any operating power or water or sewer systems, roads will be out and the problem there is gonna be managing long term refugee populations.”

There will also be aftershocks. Big ones.

“Magnitude 9 earthquakes have magnitude 8 aftershocks,” Madin said.

By the time it reaches the Willamette Valley, the effects are expected to be less staggering. People are still at risk – up to 1,473 people could die in Multnomah, Washington and Clackamas counties, according to DOGAMI. Tens of billions of dollars worth of damage could be done. But the biggest hurdle will be a long recovery process, dealing with breaks in the power system, damaged bridges and breaks in water lines.

“It’s not going to look like the end of the world, but it’s going to be extremely inconvenient for months or perhaps years,” Madin said.

East of the Cascades in places such as Bend, the damage will be light, but the social impact will be heavy.

“They’ll be the beachhead for recovery for the rest of the state,” Madin said. “And anything they used to get from Portland, they won’t get anymore.”

Preparedness is key

Whether you’re in the inundation zone or the Willamette Valley, preparedness is key to survival, Madin said.

If you’re visiting the coast, pick up an evacuation map. They show the best routes to high ground, assembly areas and more.

“Stretch your legs by walking the evacuation route. Now you know how to do it and then go have fun because you don’t have to worry about the tsunami anymore,” Madin said.

For those outside of the inundation zone, you should have a plan for what to do when the earthquake hits, including family reunification. Experts also advise having at least two weeks worth of supplies.

On the bright side, Madin said if you’re prepared for the Cascadia earthquake, you’re prepared for all sorts of less catastrophic disasters.

“Get yourself prepared and then you don’t have to worry about it.”