Editor’s note: This is part two in a series looking at how the pandemic has impacted women in the economy and workforce. Click here for part one.

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — It’s been a wearisome year for Jennifer Murray. She’s been under-employed during the pandemic, going through a separation with her husband, falling behind on rent, all while struggling to help her kids with distance learning.

Most days, Murray would wake up at 5 a.m. and stay up until midnight to get her hours in at work. The middle of the days were usually consumed by school.

“I have a kindergartener and a second grader, they’re both like pre-readers,” Murray said. “They’re too young to do that independently. You have to have an adult.”

When the kids started hybrid in-person learning, it added another challenge. Murray now drives 20 minutes to get them to school, spends two hours and 15 minutes working in the car while her kids are in class, and then drives 20 minutes home.

She said if her kids had gone back to school full-time, it would have made her life a lot easier. Instead, Portland Public Schools only gave families a hybrid in-person option. So, Murray has decided to move her family to Bend where the school district is offering full-time, in-person classes.

“They brought their kids back [to school.] So that’s a huge incentive, right? Because now I can work normal business hours again. I can not be underemployed,” she said.

Another incentive for Murray is the fact that her kids’ father is living in Bend right now. He moved there to help his parents after they contracted COVID-19.

Murray said if Portland Public Schools had reopened fully, she doesn’t know if she would have even considered moving.

Michelle Walker, from McMinnville, said she also placed her daughter in a new school so she could go to in-person classes full-time. Walker said when the pandemic started, she stayed home with her daughter. In 2020, she was supposed to start taking over the family business, but because she was working from home, the plans for her to take over have been delayed. In February, she enrolled her daughter at a private school.

“It’s been a lot better for our family,” Walker said. “We’re blessed, but I mean, there are sacrifices being made to accommodate that cost.”

Murray said when you’re a working mom “you just figure it out.” For some moms, figuring it out means leaving their jobs.

“We need to remember that childcare and education, but really having a safe place for kids to be, has always been key for women in the workforce and that when kids need care, disproportionately, that’s going to fall onto women,” said Grayson Dempsey, interim executive director of Dress for Success, a non-profit that helps women obtain the skills and wardrobe needed to find and obtain jobs.

From February 2020 to February 2021, a net 2.4 million women left the workforce, according to the Pew Research Center.

Dempsey said not only did a lot of women lose their jobs because of the pandemic, but many are struggling to go back to work because schools are closed and child care facilities are operating at limited capacities.

“The data indicates that yes, women have been leaving the workforce due to childcare needs or, you know, they may have had their hours reduced and it doesn’t pencil to pay for childcare if the majority of your earnings are going to be going towards just keeping your essentials,” explained Rep. Karin Power, head of the Oregon House Committee on Early Childhood.

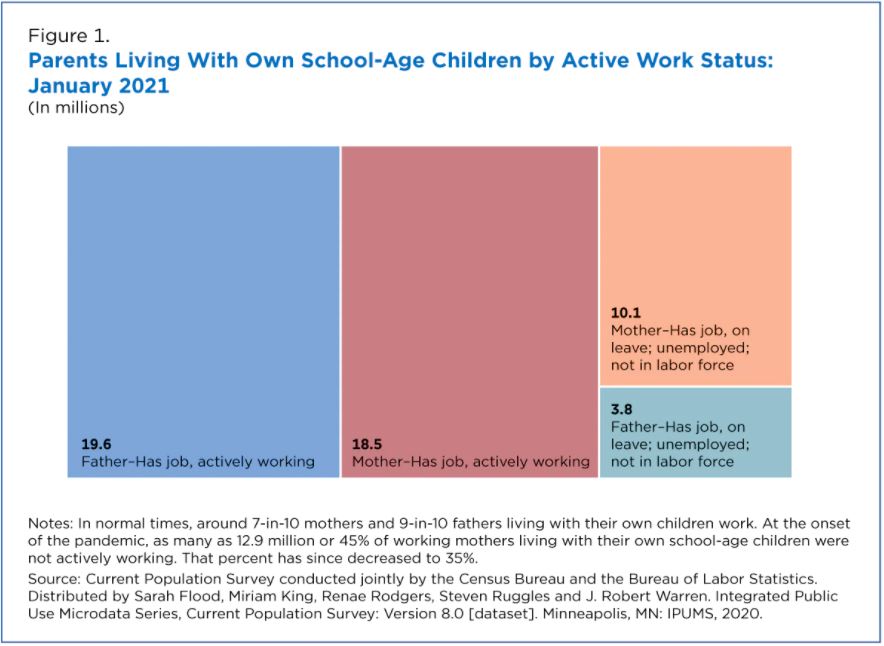

According to U.S. Census Bureau data, about 10 million mothers who live with school-age children were not actively working in January 2021. That’s 1.4 million more than in January 2020. The current population survey shows that those 10 million mothers who aren’t working account for more than one-third of all mothers living with school-age children in the U.S.

In comparison, the U.S. Census Bureau said in January 2021, about 3.8 million fathers who live with school-age children were not actively working.

Portland mother Sarina Lee was working as a wood coating specialist when the pandemic caused her son’s child care center to close. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act allowed her to take 10 weeks of paid expanded family and medical leave to care for her son. However, her company enacted lay-offs and Lee lost her job while she was on leave.

Lee said she needed child care so she’d have free time to look for a new job, but she said many places were only accepting children of essential workers. Since Lee was unemployed, she said they wouldn’t take her son. Many other places were at capacity.

“Finding child care has been a lifelong battle and the pandemic just definitely made it a tidal wave that kind of swallowed everything. As far as any options you did have, they quickly dried up,” Lee said.

She eventually found a new job and a place for her son, but soon after, the facility had its emergency child care license revoked. When that happened, Lee said she considered quitting her new job because she didn’t know what to do for child care.

Because of the difficulties finding child care, Lee’s 6-year-old son could not start kindergarten on time. After continued searching, Lee found a new day care and her son was able to start classes partway through the year.

“There’s always an option out there, even if it’s not an easy option to reach or to find,” Lee said.

While there are child care options out there, they are extremely limited in Oregon. Even before the pandemic, the state struggled to meet the demand.

A report published May 24, 2021, from Oregon State University shows that as of March 2020, all 36 counties in the state were considered child care “deserts” for children ages 2 and under. That means there are at least three children under the age of 2 for every available child care slot in the county. Twenty-five other counties qualified as child care deserts for children ages 3-5.

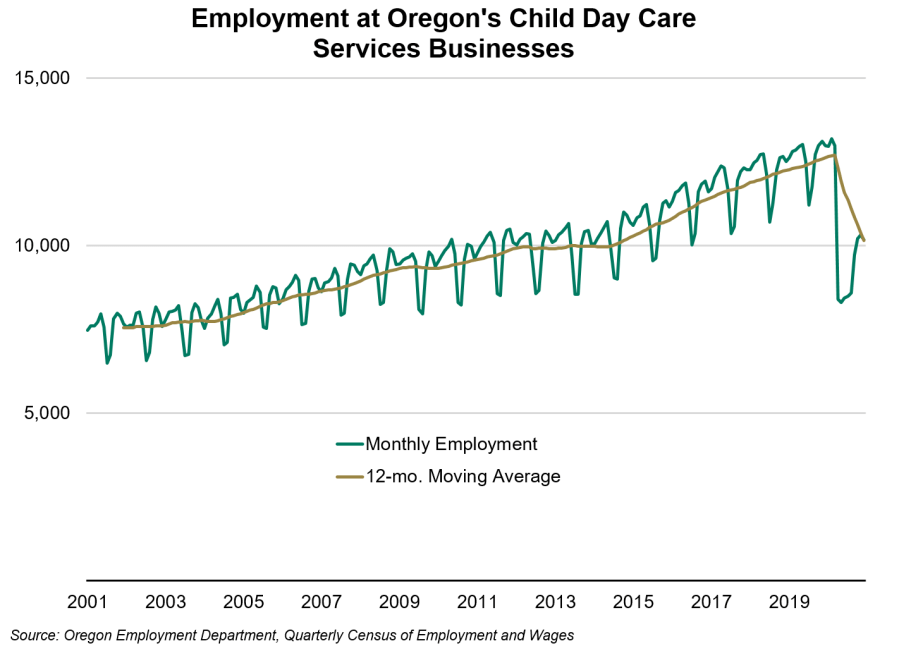

Between March and April 2020, the State of Oregon Employment Department said the private-sector child care industry dropped 35% of its jobs. As of December 2020, the industry had only regained about 40% of those losses.

According to data from the Oregon Early Learning Division, the number of child care facilities in the state declined about 15% between April 2019 and April 2021.

A survey published in April by Portland State University, the Oregon Department of Education’s Early Learning Division, and OLSC Developments, Inc. showed that 60% of Oregon families experienced a disruption in child care due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finding child care in the Portland area is so competitive and challenging that Ren Johns has made a business out of it. Her company, PDX Waitlist, helps child care providers manage their waitlist and also helps parents with the application process.

“I definitely get more calls than ever lately,” Johns said. “It’s not uncommon for providers telling me they’re getting 15, 20 calls a day of people looking for child care.”

Johns said around mid-January, when it started to look like COVID-19 vaccines would soon be widely available, a switch flipped in a lot of families. She said parents started feeling like it would be safe to go back to work, or they were getting tired of working from home while also caring for their children.

However, once many of them made that decision, they soon discovered that fewer child care centers were open. And some, who would have liked to send their kids to child care, realized they couldn’t afford it.

Data from The Economic Policy Institute show that at an average annual cost of $13,616, infant child care is more expensive than the average annual price of college tuition in Oregon – $10,363.

“Once you have a second kid, it’s easily more than most folks’ mortgage,” Johns said.

For Luisa Bernal, a mom who works a minimum-wage job in Portland, the cost of child care forced her to make an extremely difficult decision.

“I just woke up one Sunday and I told my son, okay, we’re flying to California. You’re going to stay with grandma for a few months,” she said.

That was in March 2020. She tried to bring him back in September, but at the time she was renting a single bedroom in a house. The house was infested with rats, she said. It wasn’t a safe environment for her son. She had to send him back to her mother in Los Angeles.

Since then, Bernal reapplied and was approved for county child care assistance. When she spoke to KOIN 6 News on April 25, 2021, she said her son was coming back to live with her in a few weeks.

Still, the separation took a toll on her.

“I was so angry. I was so depressed. I would come from work and just stare at my TV just hours until I snap out of it and it’s 11 o’clock,” she said. “That was my daily routine this whole year.”

School closures and the lack of child care aren’t the only two things restricting women’s return to the workforce. Career experts like Dempsey from Dress for Success say many women also struggle with a lack of resources needed to do things like work remotely during the pandemic.

“A lot of our clients don’t necessarily have home office setups and for women who used to rely on places like libraries and community centers for their primary access to technology, they may be really having to increase their wifi capability in their home,” she said.

Women who lost jobs in the leisure and hospitality industries have limited options, if they want to return to that sector. Oregon Employment Department data show the number of leisure and hospitality jobs in the state in April 2021 is down about 19% from February 2020.

Dempsey said women she’s spoken to are also afraid to go back to an industry where workplaces might open and close again as risk levels throughout the state change.

“If you’re 50 years old and you’ve worked in the restaurant industry your whole life… to not only lose your job, which is always going to be devastating, but to not know when that industry is even going to be hiring again, is a really scary prospect,” she said.

Dempsey said she’s also seeing women in their 50s who were laid off from jobs they’ve held for over a decade. She said figuring out how to apply for and get jobs right now can be scary for them.

She’s also noticed that women are looking for jobs with more flexibility. If their kids do go back to day care or school, moms say there’s always the chance their child will have a runny nose one day and will be expected to stay home and quarantine.

While women’s job losses might be on the forefront of people’s minds right now, Dempsey fears women’s careers could see the effects of this pandemic long after it’s over.

“There are a lot of challenges,” she said. “It’s going to take all of us to make sure women don’t lose ground as a result of this economic recession.”