AMITY, Ore. (KOIN) — The small farming community of Amity, Oregon sits in the middle of wine country, surrounded by rolling hills and vineyards. But this picturesque community is dealing with an issue that often goes unseen: outdated water infrastructure.

Some city water pipes are so old, they’re made out of wood.

“It’s kind of like surgery, fix the most important thing first… We’re doing the best we can,” explained former Amity Mayor Ryan Lehman. “Projects that larger cities would do in the blink of an eye, sometimes we have to just push them off because we just can’t afford to do them.”

With a population of under 2,000 people and even fewer ratepayers, Amity has struggled to cover the cost of replacing its old pipes, meters, and intake system.

It’s now more than five years into a water infrastructure project it’s paying for with grant and loan funding. The project involves moving its water intake from its current position on the South Yamhill River to a new location that will allow for cleaner water to enter the system. It’s also replacing piping to its water treatment facility and repairing water storage tanks.

The city’s largest water tank, which holds about a million gallons, had been out of commission for several years due to deterioration.

With its small number of ratepayers, Lehman said it hasn’t been easy for Amity to get approved for loans, since they don’t have many people to help pay them back. At this point, with the debt load the city has, Lehman feels it really shouldn’t take out any more loans.

To help cover the cost of projects and pay back the loans, the city has increased its sewer rates, which Lehman said people weren’t happy about. The city will also increase its water base rate in January 2022 from $48 to $63. However, that new base rate will include 2,000 gallons of water, which Lehman hopes will help his low-income residents.

“Hopefully, for a majority of people, it’s going to even out. And for those people that use substantially less water, it’s going to actually hopefully be a cost savings for them,” he said.

Lehman said the city has been incredibly fortunate to receive grant funding from the American Rescue Plan Act that it plans to put toward replacing its water meters and water main pipes throughout the city.

At this point, Lehman said he’s feeling optimistic about the outlook for the major water infrastructure project in his city. The project is expected to be completed by the end of 2023. In the future, he’d like to see more funding made available for infrastructure on the state and federal levels, especially for small, rural communities.

“It’s taken us a long time to get here. It’s cost us a lot of money, but it’s coming to fruition slowly but surely, so I’m positive with that,” Lehman said.

Amity’s situation isn’t unique. A survey conducted in late 2020 by the League of Oregon Cities and Portland State University’s Center for Public Service outlined how many cities fall short of funding necessary water infrastructure projects.

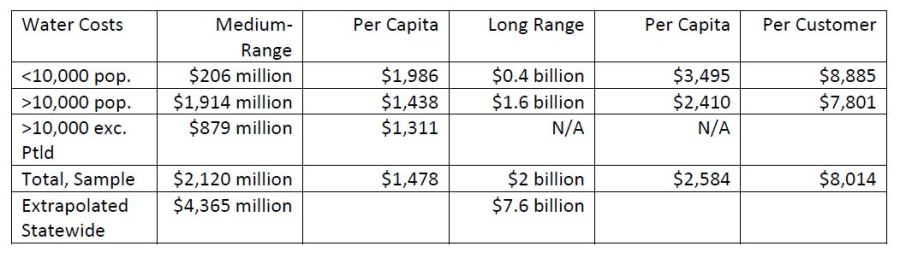

The survey results, which were from 100 of Oregon’s 241 cities, indicate they have $9.7 billion in water infrastructure needs.

With these data, PSU estimates the state will have approximately $23 billion in water infrastructure costs in the coming 20 years.

“People throw around billions of dollars here and there on the cost of infrastructure, but in the case of water and wastewater… I think people’s estimates are probably pretty accurate. If anything, they underestimated,” said Scott Lazenby, an adjunct associate professor at PSU who helped lead the survey.

The survey found that cities with lower-income populations are disproportionately impacted when costs and regulations increase and at this point, many communities can’t afford the necessary infrastructure.

It also highlighted how the anticipated per capita cost was significantly higher for smaller cities than for larger cities.

The estimated per capita cost of paying for infrastructure over the next 10 years for Oregon cities with a population of fewer than 10,000 people was $1,986. For populations of more than 10,000 people, the estimated cost is $1,438.

Infrastructure issues aren’t just a concern in Oregon, the entire country has the need for improvements. In 2021, the U.S. earned a C- on its infrastructure report card. Oregon scored the same overall grade when its last infrastructure report card was released in 2019. Washington State scored a bit higher with a C.

A “C” grade equates to “mediocre,” meaning the infrastructure is in fair to good condition, but shows general signs of deterioration and requires attention.

Of all the categories, Oregon scored the lowest grade, a D, for its wastewater infrastructure. Washington scored its lowest grade for stormwater, with a D+.

The grade summary says many of the wastewater systems have been in use longer than originally intended and will soon need replacement or full rehabilitation. The report says engineers, planners, and managers must decide how to allocate available funds, which almost always fall short of what’s needed to achieve comprehensive system improvements.

In Amity, the former mayor said more of that funding needs to come from the state and federal government because cities like his can’t foot the bills on their own.

“I hope that in the future infrastructure-related bills that are passed at the federal level focus more on infrastructure,” he said, “because that is really what I consider the nuts and bolts of each community.”

Note: Former Mayor Ryan Lehman resigned from his position as mayor on Aug. 4, 2021 for personal reasons.