PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — For 27 years, Phil Prewett worked at the Oregon Zoo, much of that time with elephants. He retired three years ago and gets “almost misty-eyed” when he thinks about his favorite.

“Rose was God’s most perfect elephant,” he told KOIN 6 News.

Over the years he also worked as a rover, doing whatever was needed. He was also an Africa keeper and a night keeper, moving the elephants and feeding them.

“The animals were not always treated with as much kindness as one could offer,” he said. “I’m still getting chills about on the night shift, the night keeper will come down and on some occasions in the winter you’ll have three bulls in the back in the room.”

Not all elephants are easy to handle, he said. “Adult male elephants are a force of nature.”

He said the Oregon Zoo wants desperately to breed the elephants.The breeding plan

Since the 1990s, a dozen zoos across the county have closed their elephant exhibits, with another five planning to do the same. Those that plan to keep their elephant exhibits open — like the Oregon Zoo — will always need elephants.

That requires breeding.

Documents obtained by KOIN 6 News detail a history of efforts to collect semen, inbreeding and cross-breeding of subspecies.

In 2011, documents showed the Oregon zoo had plans to breed Chendra and Tusko, both Asian elephants but from different subspecies. That document showed the Oregon Zoo planned to breed Chendra with Tusko every four years.

Chendra, at just over 4500 pounds, is said to be the only Borneo pygmy elephant living in the US.

Tusko weighs 13,300 pounds. The 8755-pound difference between the two is more than Tusko’s other partner, Rose Tu, weighs.

“Tusko is a huge animal in every respect including his manhood and I think in borders on animal abuse to put such a large male in with such a small female,” said former elephant keeper Prewett.

KOIN 6 News found a published a study against breeding Borneos — like Chendra — with Asian Elephants or other subspecies.

Similarly, the American Association of Zoos and Aquariums, which accredits zoos across the county, posted an article in 2010: “The Bornean elephant is a separate taxon.“

The AZA also called Borneos the “world’s most endangered elephant.”

Neither the Oregon Zoo nor the AZA responded to requests from KOIN 6 News for comment on the Chendra-Tusko breeding plan.

Dr. Robert Hilsenroth, the executive director of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians, told KOIN 6 News breeding Chendra and Tusko is a bad idea.

“It would be detrimental. It wouldn’t contribute to the sustainability of our elephant population,” he said.The Stud Book

The AZA keeps a list of all the approximately 750 elephants ever known in the US and parts of Canada. The list is known as The Asian Elephant North American Regional Stud Book.

A review by KOIN 6 News found a pattern of inbreeding at the Oregon Zoo about 30 years ago. Most of the offspring died shortly after birth.

“There’s a much higher risk of genetic defects,” Hilsenroth said. “Some of these are fatal defects, some of them they can live with, some of them are just cosmetic.”

Each elephant in the studbook is given a number. Then there are a set of two other numbers in the center of each listing. Those can be cross-referenced back to the parents, making it possible to trace an elephant’s lineage.

It’s a little like cracking a code.

The non-profit animal group Zoowatch said it’s meant to be that way.

“I don’t think they want the average person and particularly not an investigative reporter to be able to easily digest the information,” said Zoowatch’s Julie Woodyer. “It’s something that the industry themselves likes to be able to interpret for you.”

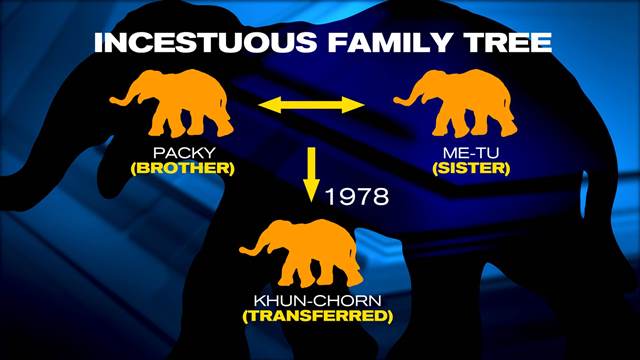

The Stud Book reveals an incestuous family tree at the Oregon Zoo: five births over five years at the Oregon Zoo from inbreeding daughter with father and brother with sister.

— Thonglaw was bred with both his daughters, Me Tu and Hanako. Both male offspring were born in 1973. One was unnamed and died immediately. The other, Stretch, was transferred to Florida. But no trace of him was found in a KOIN 6 News search.

An Oregon Zoo spokesman said, “I have no information on Stretch.”

— Packy was inbred with Hanako, and in 1976 an unnamed calf was born but died less than a month later.

— In 1978, a female calf named Sumek was born, but again died about a month later.

— That same year, Packy and his other sister Me Tu gave birth to Khun-Chorn, who was transferred to Dickerson Park Zoo shortly before turning 2. He is still alive.

The Oregon Zoo declined an interview on the specific subject of inbreeding but sent an email with this statement:

“Inbreeding is not something that would be likely to happen in the wild, nor is it something that would happen at the zoo today.”Artificial insemination

Phil Prewett started after the Oregon Zoo elephant inbreeding stopped. He said those inside the elephant circle knew about it.

“They just kind of inwardly, in-house, admitted that it’s a bad idea. We don’t do that anymore.”

But he said the zoo was determined to try and grow the elephant herd the entire time he worked there.

Artificial insemination took place at the Oregon Zoo, he said, “but no conception took place.”

A zoo spokesperson said in a statement they don’t have much information on their artificial insemination attempts.

“To be clear, this is not to say the zoo is opposed to AI, just that it hasn’t been attempted here for many years.”

The AZA’s Species Survival Plan given to the Oregon Zoo makes it appear AI will start up again. The chart lists Tusko as “available as AI donor.”

The zoo spokesman added, “On the recommendation of AZA’s Species Survival Plan, some of Tusko’s semen was sent to other zoos, and semen from all the males has been collected to assist in research projects. “

Another elephant, Sumundra, is to be “train(ed) for AI once age appropriate.”

Prewett, who said he “was involved in some of the semen collection,” said it’s a graphic process that’s not easy on the elephants, who would be stimulated electrically in their rectums.

In 1999, there were repeated, unsuccessful attempts to collect semen from Packy. At one point, the staff even tried to take a collection when Packy was “unwilling to move.”

Zoo officials said all 28 of the elephant births have been natural, including the five from inbreeding.

The reason zoos keep pushing hard to breed elephants is, according to the AZA, “Zoo populations of both Asian and African elephant species are not currently viable without importation.”

In other words, without taking elephants from the wild, zoos will run out of elephants.About Asian ElephantsAsian Elephants are considered an endangered species and are protected through international trade rules from established in 1963 from the Convention on International Trade and Endangered Species. There are three rankings, with the endangered animals falling under Appendix I. The United States ratified CITES in 1974 and the Asian elephant was placed in Appendix I of CITES in 1975. CITES controls international trade of these animals by requiring all imports and exports of the animals covered by CITES go through a licensing system and have a grant and permit after certain conditions are met. Under Appendix I, to export the Asian Elephants export permits can only be given when scientific authority has been proven it won’t be detrimental to the species. It also must show the animal was obtained legally and the shipment process will minimally risk injury or cruel treatment to the elephant as well as prove the importing country has the necessary importing permit, showing the receiving recipient is fully prepared to appropriately care for the animal. Additionally, the reason the elephant is being imported cannot be for commercial purposes.In the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants the Asian elephant is classified as endangered. This means that all elephants, both Asian and African that are imported into the United States must also meet the USFWS’s rules. The USFW restrictions are actually stricter than CITES on the U.S. front. Most zoos need to undergo inspections of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) and all meet their guidelines. US Congress passed the Asian Conservation Act of 1997