PORTLAND, Ore. (PORTLAND TRIBUNE) — Nine years ago in Portland, a 15-year-old Catholic schoolgirl struggling with her sexuality told her sophomore English teacher: “If I was drunk, I would kiss you right now.”

She was surprised by what she says was her teacher’s response.

“I wouldn’t even have to be drunk.”

There, at her teacher’s house in April 2009, was when Ariana Garay felt their relationship had crossed a line. At the time, she was thrilled. She felt special and wanted.

But now she has a different take on the relationship.

“As a (nearly) 25-year-old,” Garay said recently, “I can tell you that I should have never been over at her house in the first place.”

This is a Me Too story like few others.

While most allegations of school-related sexual misconduct focus on male instructors abusing students, Garay said hers is a story about a two-year sexual relationship with her female teacher at St. Mary’s Academy, a prestigious Catholic high school for girls in downtown Portland. It’s a story, she said, of a girl growing up and coming to terms with the woman who, at 11 years her senior, took her virginity and left her with lasting psychological scars.

Garay hopes her story, accompanied by emails and texts with her former teacher, will add different testimony — from the gay and lesbian community — to the Me Too movement sweeping the country since the October 2017 publication of a New York Times investigation of movie mogul and alleged sexual predator Harvey Weinstein.

Finally sharing the story, Garay said, has liberated her from having to keep these secrets.

“I don’t want to be scared anymore. I think my biggest fear has always been somebody would find out,” Garay said. “For so long I carried that guilt and responsibility for actions taken by an adult when I was a child.”

Teacher: It was never physical

Her former St. Mary’s teacher, Francesca Cronan, tells a different story, a reaction similar to many others accused in the Me Too wave: blanket denial. Cronan conceded her relationship with Garay was

inappropriate and included sexualized conversations, but she maintains it never progressed to physical intimacy.

“Obviously, I’m disappointed and concerned about Ariana’s mental stability manufacturing these claims at this stage, long after the teacher/mentor relationship ended, and I’m hoping she’ll get the help that she needs,” Cronan wrote in an email to the Tribune.

Cronan said her use of code names and code words in emails with Garay, which seem to refer to explicit sex and the need to cover up their relationship, was simply a matter of “placating and playing along” with a student who might otherwise blow the whistle on a nonsexual but inappropriately close friendship.

“At no point did we ever have sex. Not in the house, not in the car, not ever,” Cronan said. “The only (wrongdoings) I acknowledge are related to the email correspondence, which crossed a line in my attempts to placate Ariana.”

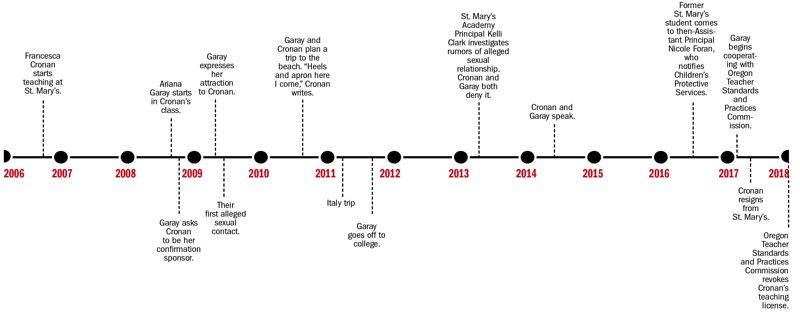

The Oregon Teacher Standards and Practices Commission agreed the correspondence crossed a line. After investigating Cronan’s relationship with Garay, the state agency and Cronan agreed to an order revoking Cronan’s Oregon teaching license on Jan. 19. The TSPC report states Cronan violated several rules, including “any sexual conduct with a student.”

Cronan’s lawyer, Richard Davis, said this stipulation refers only to the graphic communications, and he described Garay’s version of a physical sexual relationship as an elaborate “fairy tale” concocted as a form of emotional blackmail.

“When my client attempted to impose boundaries, Ariana impliedly threatened to reveal the emails and texts,” reads a March 21 letter by the California attorney. Davis and Cronan did not provide documents or witnesses to substantiate their version of events, as repeatedly requested by the Tribune.

Cronan herself graduated from St. Mary’s Academy in 2000, in the top 5 percent of Oregon students, according to the Catholic Sentinel newspaper. After graduating from Occidental College in Los Angeles in 2004, she began working at St. Mary’s in 2006. According to her LinkedIn profile, she attended Portland State University from 2007-09 to earn her master’s degree in education.

Her return to her alma mater had not been a goal of hers. “It was happenstance; a position was open when my husband and I planned to move back to Portland,” Cronan said in an email to the Tribune.

Judging by online teacher ratings, she became a favorite among her students.

“ANGEL! MY FAVORITE TEACHER,” reads a Feb. 13, 2017, review on RateMyTeachers.com. “I am her biggest fan and she will be a lifelong mentor.”

Seeking a confirmation sponsor

In 2008, Garay became one of Cronan’s new students.

Like many people at 15, Garay, by her own admission, was awkward and struggling with her identity. She didn’t really know what lesbian was, other than as a slur. She was more concerned about how to accomplish her Catholic confirmation, a coming-of-age rite that required an adult to be her sponsor. She had asked a friend’s mom, but that woman didn’t have time.

“I was just trying to find somebody at that point,” Garay said.

She felt a connection to her English teacher, so she asked if Cronan would be her sponsor and the teacher agreed. Garay said they would meet for coffee once or twice a month and go for long walks in Laurelhurst Park, talking about life.

By spring of her sophomore year, Garay said she expressed her attraction to Cronan. She said her teacher confirmed her own desire for Garay but also said the teacher delayed sex until after Garay’s 16th birthday, two weeks later.

The first time they kissed, Garay said, was on a Saturday. She doesn’t remember the date, but she said the weather was nice and school was still in session, so it was probably May. At the end of a meal at Pok Pok, they walked in opposite directions but met up at Cronan’s car, she said.

“We kind of tried to hook up, but there were too many people walking by for us to actually have any privacy,” she said. Garay said the two made out again about a week later in a car, prior to a jewelry party hosted by a St. Mary’s mom.

Garay said she doesn’t have clear memories of when she lost her virginity, other than that she was scared.

“I remember being extremely scared and shaking. I didn’t feel comfortable, but I also felt like I had to. She always talked about how I seemed older than I acted. I couldn’t admit that I wasn’t ready,” she said.

Lots of emails, texts

During Garay’s junior year, in 2009-10, their relationship deepened. Garay said they had sex about 50 times in all, usually after school at Cronan’s house but sometimes during finals week or when the teacher’s husband was on a business trip.

Aaron Cronan, the teacher’s husband, said that’s impossible because he was working from home during that period.

Garay disputed this assertion. “He may have been working from home, but I never saw him,” she said. “I would assume that’s not true.”

One point on which all agree is that there was a large volume of emails and text messages between them. Cronan’s husband told TSPC investigators that it had been “annoying.”

However, Garay could only produce a dozen emails she said were to or from Cronan, which she said somehow escaped a purge in 2013, during a St. Mary’s investigation. She said she deleted the rest, at Cronan’s urging, because she didn’t know what law enforcement could do, if they were conducting surveillance.

Through her attorney, Cronan said it was reasonable for her to ask for the messages to be destroyed.

“As long as those written communications existed, Ariana could use them as leverage,” Davis said. “As Ariana’s fabricated tale of a sexual relationship establishes, my client’s concerns were well-founded.”

‘Orange juice’

By the summer of 2010, when the majority of the messages Garay produced were sent or received, they were exchanging messages with graphic sexual content.

On July 27, 2010, Cronan started a gmail chat with: “MUFFIN!!!!! EEEEEEEEEEEEEEE”

As that conversation progressed, Garay said she would “push you to the bed” and “have my way with you.” Cronan responded: “awwwwww shucks <3” and “well, hello there 😉 Hehe.”

The English teacher, who also occasionally freelanced for Hollywood screenwriters, told the state investigator she adopted the name of “Carmen” to help Garay role play what being in a homosexual relationship would be like. The name referred to a character from “The L Word” television show about a group of lesbians in Los Angeles. The teacher even used an email address for their discussions that alluded to this fake name; its first four letters were CRMN.

In one email exchange, they discuss possibly renting a Neskowin beach house, which both say never actually occurred.

“You in heels and an apron and me in complete bliss,” Garay wrote.

“Haha! Heels and apron, here I come!” Cronan responded in an Aug. 1, 2010, note signed “Tu Carmen ;)”.

There also were references to “oranges” or “orange juice,” which Garay said was their code for sex. Cronan maintains it referred to Garay’s romantic feelings for her.

“P.S. ….Orange juice pleeeeeeease!!!!” Cronan-as-Carmen signed off in an email dated July 28, 2010.

“P.S. “MmmmsoundsgoodbutIgettotakesomeofyourjuicefirst,” Garay responded.

In another email, Cronan-as-Carmen refers to another persona — “Polly” — which Garay said represented the teacher’s paranoia.

“…Polly is on high alert right now…” Cronan wrote Aug. 2, 2010, in an email signed “C ;)”. “So please, be extra vigilant about everything. I know you are, but I beg that it be even more on lockdown.”

“…be extra vigilant about everything. I know you are, but I beg that it be even more on lockdown.” — Francesca Cronan

Role play?

The 14 pages of emails were included in the nearly 200 pages of TSPC investigation documentation, along with several screenshots of text messages and additional chat discussions. Cronan told investigators that by the time she realized the sheer volume and quality of these “fantasy” messages they exchanged, she “decided it was better to continue going forward, get (Garay) graduated and move past it,” according to TSPC investigator Cristina Edgar’s preliminary report.

Garay said she finds Cronan’s explanation of their communications as role play abhorrent.

“That just makes me so uncomfortable,” Garay said. “That is quite the explanation. And just disgusting, in my opinion.”

Victor Vieth, senior director and founder of the Minnesota-based Gundersen National Child Protection Center, said Cronan’s argument that Garay was the one pushing boundaries with an obsessive fantasy goes back at least to the days of Sigmund Freud.

“That argument is very old and largely universally discredited in the literature,” Vieth said. “But I would go one step further — it is irrelevant. This is a school teacher. The teacher should know that engaging in sexual conversations with the child would jeopardize her job.”

Classmate saw them together

Toward the end of Garay’s senior year, a classmate said she witnessed Garay and Cronan together in a hotel room on a spring-break class trip to Italy in 2011. The woman declined to be named in this story but confirmed to the Tribune what she told TSPC investigators.

She said Garay had said she was in a relationship with a married woman. On the trip, she was roommates with Garay and saw her sneaking out of their room early in the morning. When she went to look for her a little later, she knocked on Cronan’s door and found the teacher chaperone in a “state of disarray” and saw Garay emerge from hiding in the closet, her clothing disheveled.

Davis, the attorney who serves as litigation counsel for Cronan, argues that Garay’s classmate’s claim of catching them together is illogical.

“There is just one problem,” Davis wrote to the Tribune. “If there were a secret sexual relationship, opening the door to reveal Ariana in a state of undress would be a sure-fire way to break that secret wide open. That incident simply never occurred.”

The classmate who said she saw Garay and Cronan together in Italy stands by her story, and also told the Tribune she once saw the two in Portland, leaving Cronan’s house together.

At college, Garay struggles

TSPC records indicate rumors of an inappropriate relationship began swirling at St. Mary’s in 2011, though the principal at the time, Pat Barr, told TSPC investigators that she had no records of it, no memory of it and that she would have investigated it.

Garay said she stopped most communication with Cronan when she went off to study at the University of Oregon in the fall of 2011. It was there that Melissa Wong, a fellow graduate of St. Mary’s class of 2011, became her roommate and best friend.

Wong, a Portland resident, said she never saw Cronan and Garay together at St. Mary’s, but she witnessed years of Garay struggling with anxiety over the relationship while in college.

“As she told me more, she mentioned the scenarios that Ms. Cronan would tell her to keep a secret and she would share more and more that she was feeling bad about it,” Wong said. “I was a support system during it.”

Wong added that she heard at the time of Cronan threatening suicide if Garay told of the true nature of their relationship. Garay, she said, “felt that if she confirmed anything or did anything at the time, that she would feel that weight of responsibility.”

After hearing rumors of an alleged affair, St. Mary’s then-Principal Kelli Clark conducted an investigation in 2013. It came to nothing, in part because Garay told the same story as Cronan, denying there had been a sexual relationship. Cronan told Clark at the time that she and Garay were simply “inspired by each other.”

Garay now says she lied to protect Cronan, and it was stressful for her. She drank heavily and contemplated suicide, figuring that without her in the world, Cronan’s freedom would be secure.

“I definitely hit rock bottom for a while,” she said.

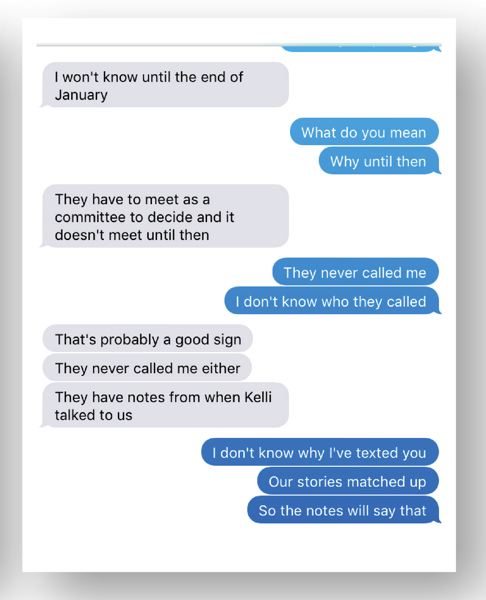

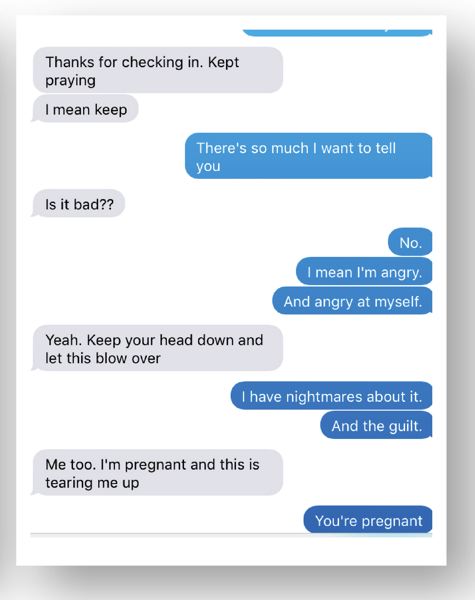

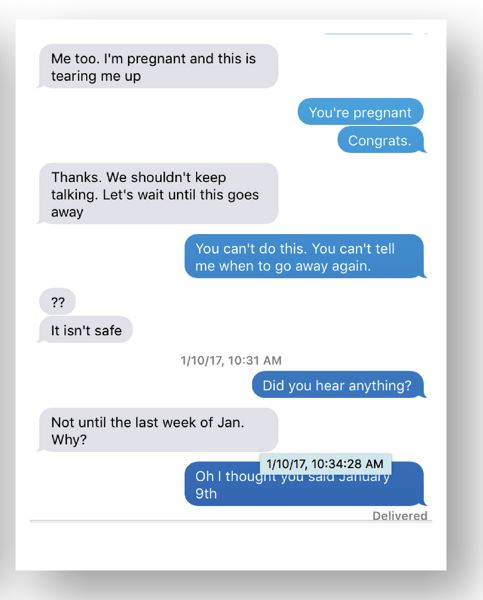

In text messages Garay exchanged with Cronan during the 2016-17 TSPC investigation, a text from Garay refers to what she contended was the 2013 cover-up to protect Cronan.

“They have notes from when Kelli talked to us,” Cronan wrote on Dec. 28, 2016.

“Our stories matched up. So the notes would say that,” Garay responded.

“Thanks for checking in,” Cronan wrote back. “(Keep) praying.”

Garay decides to cooperate

Garay did not initially participate in the TSPC investigation.

That probe started in August 2016 — five years after Garay had graduated — when her roommate in Italy took the story of the hotel incident to Nicole Foran, then St. Mary’s assistant principal and now principal.

Foran had heard the rumor before, but did not believe it. But with the statement from Garay’s classmate, she reported the rumor to the Child Protective Services division of the state Department of Human Services, which relayed the information to the Teacher Standards and Practices Commission.

The classmate told the Tribune that she finally came forward with her concerns because she was worried about several younger St. Mary’s students she knew who were attending the school where Cronan still taught.

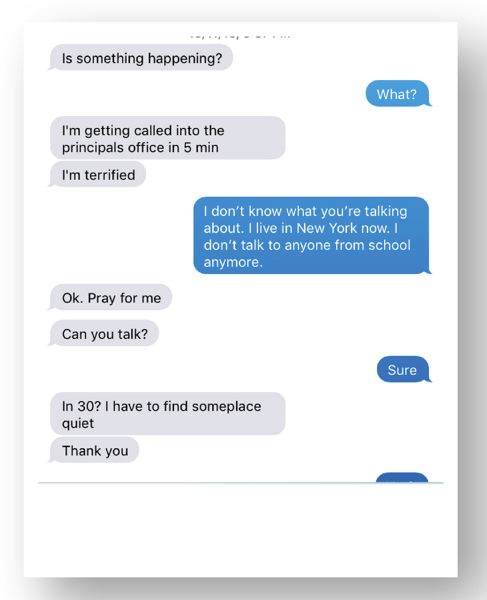

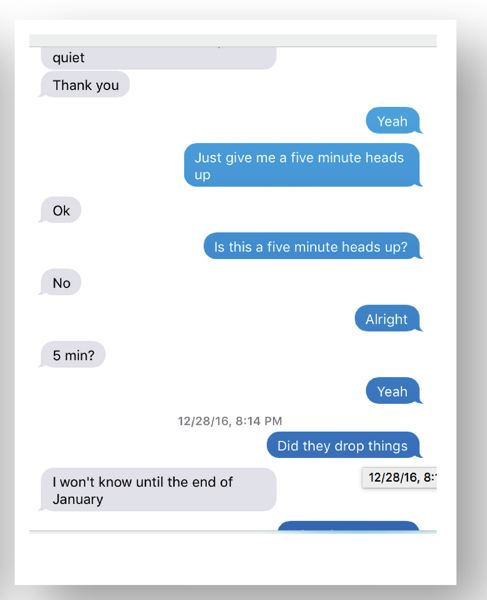

After the TSPC investigation began, Garay and Cronan exchanged text messages about it. Cronan texted Garay on Oct. 11, 2016, the same day the TSPC investigator contacted her principal, asking “Is something happening?”

“What?” Garay responded.

“I’m getting called into the principal’s office in 5 min. I’m terrified.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. I live in New York now. I don’t talk to anyone from school anymore,” Garay said.

In a December 2016 text, Garay wrote that she had nightmares and felt guilty “about it.”

“Me too,” Cronan responded.

Asked what she meant by that, Cronan told the Tribune through her attorney that “me too” referred to nightmares about being falsely accused.

Garay did not get involved in the TSPC investigation until Jan. 13, 2017, when she called the state investigator to, in her words, “confess.” She told the investigator that Cronan called her the day before to ask what questions to expect from the investigator.

In the teacher’s Jan. 30, 2017, interview with the TSPC, when the investigator asked about Cronan’s last contact with Garay, she at first said 2014. Then Cronan said she’d received a text from Garay about a month earlier. Pressed by the investigator, Cronan confirmed Garay was correct when she told the investigator the teacher called her former student on Jan. 12.

It was later revealed that Cronan also called Garay on Jan. 28, two days before her TSPC interview.

Garay said she hasn’t heard from her since.

A ‘witch hunt’

Cronan’s husband, a trademark attorney with legal offices in Southeast Portland, said he doesn’t believe the allegations against his wife and mother of his two young children.

Aaron Cronan said he fought TSPC to a “draw,” and attacked Garay’s credibility. He said she had “a history of obsessive and manipulative behavior” and a “scorched-earth policy towards people she feels crossed her,” but he did not respond to repeated requests to document this alleged conduct.

Aaron Cronan said he believes the state investigation was a “witch hunt” by “progressives” too eager to believe a bunch of “out of control” former students.

“In fact, once it became clear that (Garay’s) story was not remotely holding up, TSPC agreed to delete the witness’ claims from the stipulation — something they typically don’t do — and accepted very narrow language,” he wrote to the Tribune.

Trent Danowski, who temporarily led the state teacher licensing agency at the time of the investigation, disputed this.

“TSPC finds the statements made by Mr. Cronan to be a complete misrepresentation of the facts in this matter,” Danowski, now the agency’s deputy director, stated in an email. He said the agency sometimes negotiates with teachers to remove findings from the final document to reach agreement on a disciplinary action, such as revocation of a license — to save taxpayer money from a lengthy legal battle.

“In the Cronan case, TSPC remains firmly committed to the findings of our investigation and all of its witnesses,” Danowski said.

No reason to lie

Garay said she still feels Cronan’s psychological impacts on her life. “It made me question the idea that people actually marry for love,” she said.

Garay had other relationships in high school, but was always lying to people she dated about her relationship with her teacher, she said.

Garay said she finally came to the realization that if her younger sister came to her at 15 with a similar story of being in love with a man 11 years her senior, she would immediately tell her it was “one thousand percent wrong.” But for herself, “I couldn’t split the two because that guilt has always been driven into my head.”

Garay no longer lives in Portland and said she is stricken with fear every time she comes back to visit her parents that she will run into Cronan or former classmates.

She said she declined to press charges against Cronan because she doesn’t ever want to see her again and doesn’t want this to drag on longer. She also said she hates how this will hurt Cronan’s family.

Garay said she has no reason to lie now.

“Why would anybody make up a story like that?” she wonders. “Why would people willingly come up with a very traumatizing story like that?”

She said the most that society can do now for people like her is “believing the victims and making sure that we continue to foster a place where victims feel empowered to come forward, but they, most importantly, should be coming forward on their own terms.”

Garay didn’t want to file a police report

Portland Police Bureau Sgt. Molly Daul, who heads the agency’s Sex Crimes Unit, confirmed, with Ariana Garay’s permission, that in 2017, a victim’s advocate spoke with her about her options for prosecuting her former teacher, Francesca Cronan.

“She didn’t want to file a report, so that’s why there’s no report in the records,” Daul said.

The police sergeant said that the unit takes a victim-centered approach, which is why they will not prosecute a suspect if the victim is not on board.

Sexual assault experts say that it can take years for childhood sexual assault victims to come forward.

“We do a lot of historical sex assault investigations,” Daul noted. Garay is still well within the statute of limitations — which would be up to her 30th birthday — on these sorts of allegations, she said. “She knows that whenever she wants to re-engage, she is welcome to do that.”

Cases covered in the media can be more difficult to prosecute, Daul said. But she also said that victims can “find the process (of media coverage) empowering,” particularly as cases that happened years ago can be difficult to prove in court.

Sexual assault expert sees patterns in teacher predators

An Oregon expert on sexual assault says teacher sex offenders target students who have reasons to keep quiet about the relationship or who might appear less credible than the teacher.

Susan Moen, executive director of the Jackson County Sexual Assault Response Team, says offenders also groom their victims and use psychological manipulation — fears over the consequences the teacher would suffer — to prevent them from talking about it.

“Oftentimes in teacher-student relationships, we are very clearly seeing the imbalance of power,” says Moen, speaking in general and not about any specific case.

Predatory teachers make students feel special, she says. Then the child often can feel that this is a consensual relationship, despite the level of manipulation and the law being clear that under the age of 18, children are not capable of consenting to sex.

“Particularly in teacher-student (relationships), you’re going to see a huge amount of grooming going on,” Moen says. “It’s predatory behavior, and it’s very premeditated and it’s calculating.”

In cases where victims come forward, Moen says there usually is a huge amount of backlash, as the teacher often is well-liked and a cultural “hot for teacher” narrative still exists, making it seem “cool” that a student had sex with a teacher.

“It absolutely embodies this idea that these relationships are something other than out-and-out child sex abuse,” says Moen, who also is a board member of the Portland-based national nonprofit Stop Sexual Assault in Schools.

Moen said there has not been a lot of research focused on female offenders.

But Moen says most offenders — about 70 to 80 percent — are serial in nature. They typically start their offenses around the age of 15 and may have dozens of victims in their lifetimes.

“The goal is really to just start assuming that if somebody has committed one crime, you want to look really super hard — and we train investigators to look for those multiple victims,” she says.

As a sexual assault expert, Moen often works on court cases, and says in cases where there is no direct evidence of sex, juries are typically given instructions to examine how credible they find the alleged victim and any evidence of the emotional fallout, which may come years later from such abuse.

Moen notes victims often decide to come forward out of fear that the offender will do it to someone else. Once they have, Moen says, “those other victims are going to be able to come forward and say ‘me too.’ “