PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) – One year ago, the Pacific Northwest was experiencing a tough winter blast that brought snow and ice to the region, resulting in thousands of power outages and damaged trees and halting the city of Portland.

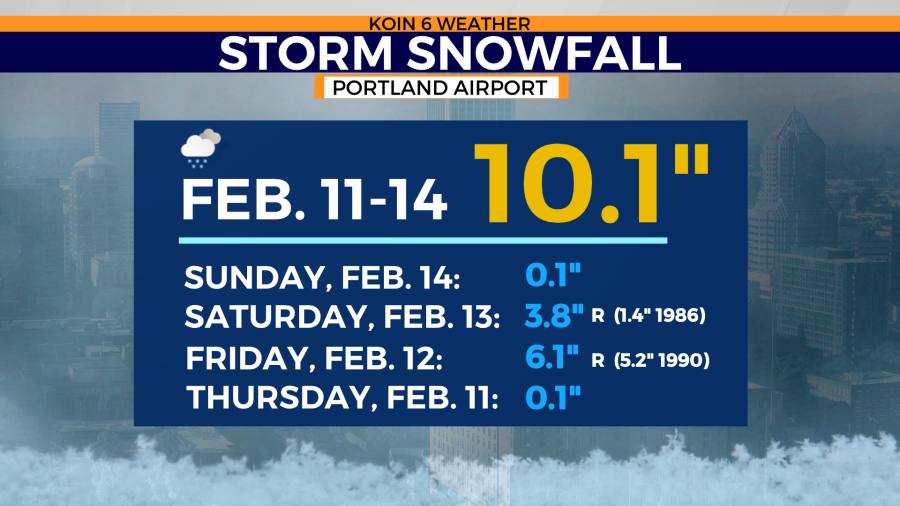

Looking back, the amount of snow Portland accumulated during the Feb. 11-14, 2021 storm was 10.1 inches.

The snow to liquid ratio is generally 10 to 1 inches (depending on the temperature). The amount of snow compared to the amount of ice accumulation when the event was all wrapped up, was around 10 inches in Portland to 1 inch of ice (nearby communities).

10:1

These totals didn’t come from one single day event, it took a period of four days from start to finish. Yes, it is a coincidence that the totals of 10 and 1 are glued to this event. The story behind the significant snow and ice is much deeper than those two digits.

HOW DID IT UNFOLD?

Two record snow events were packaged into a 48-hour timeframe. A major ice storm followed.

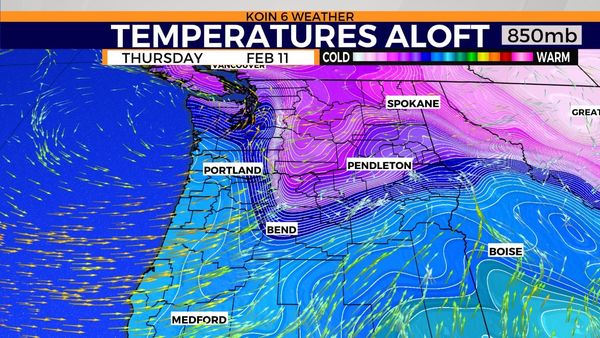

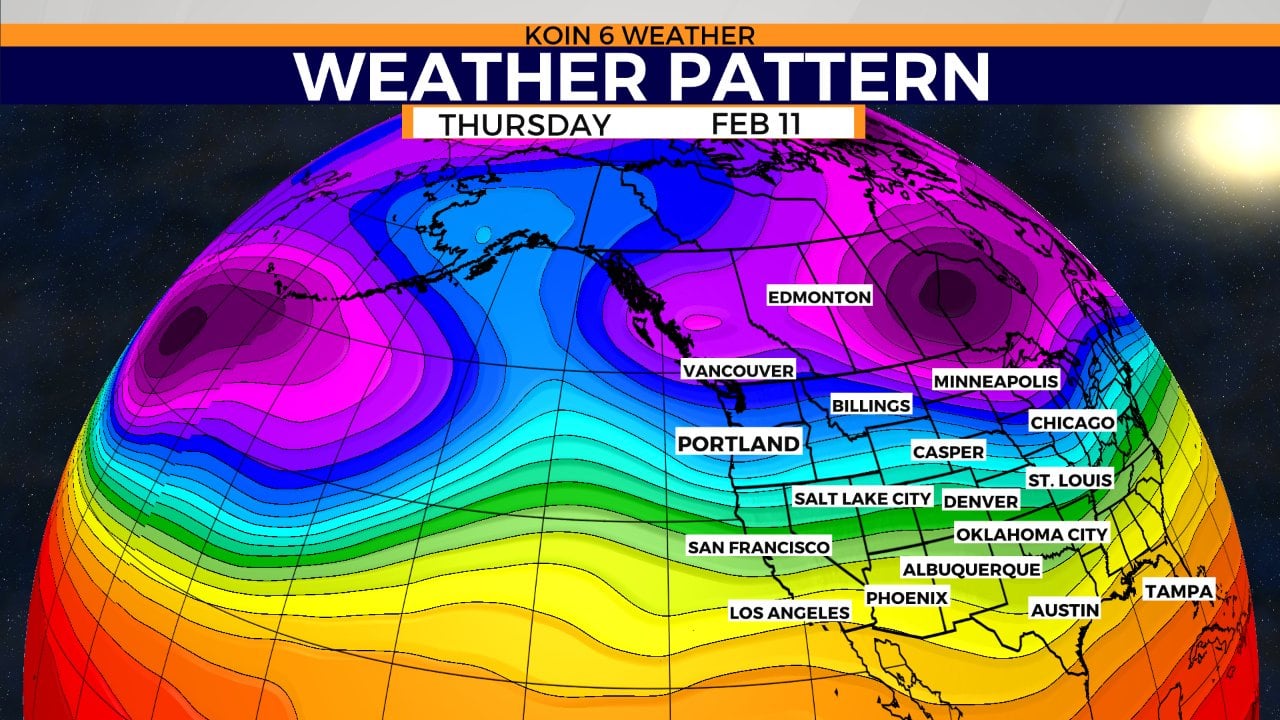

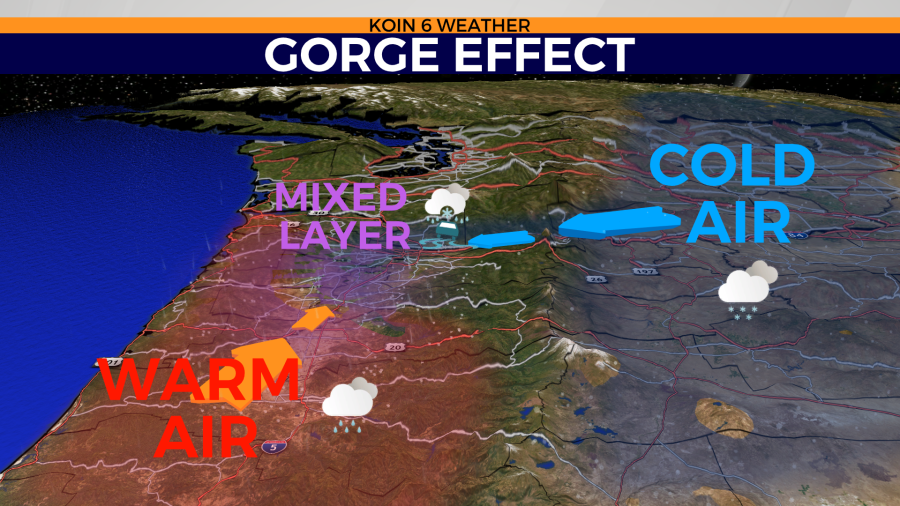

It started with a rush of arctic air coming straight from the belly of the beast, the Columbia Basin. Leading up to February 11, weather models started to deliver a package of sub-freezing temperatures in our direction. The cold air was spreading through the northern Rockies, leading to cold air advection through the eastern side of Washington and Oregon. The graphic above shows a bunch of white lines stacked tightly next to each other, with cold arctic air (represented by purple), protruding into Washington and Oregon. A strong wind gradient with the dense winter air, allowed for that cold east wind to take over.

This is generally the first step to a recipe that is needed for winter weather in the Willamette Valley. Without the Columbia River Gorge to supply a rush of cold air, we would have a difficult time cooling down the surface here in the Willamette Valley. Why? Because of the relatively warm Pacific Ocean air nearby. Each time a system moves in from the ocean, it typically brings in warmer air. We call this a wind shift and a deal-breaker for valley snow. Unless, the cold air is so potent from the Gorge, that we can withstand the rush of warmer air.

A series of surface charts, which are used to help forecast the weather, are in a slideshow below. The surface charts tell the story from a meteorological perspective. The event tells the story of what occurred from our perspective on the ground.

How did we get from snow to ice? We had two systems move in that didn’t bring in enough warm air to scour out the cold. Those were the two record snow events for Portland. It was mostly a snow event for those north of Portland altogether. When snow is on the ground, it keeps the surface cold. This is key to the development of freezing rain and ice. We didn’t have a major sleet event (although there was a time of mixed precipitation), we had more of a freezing rain event, that lead to major ice accretion.

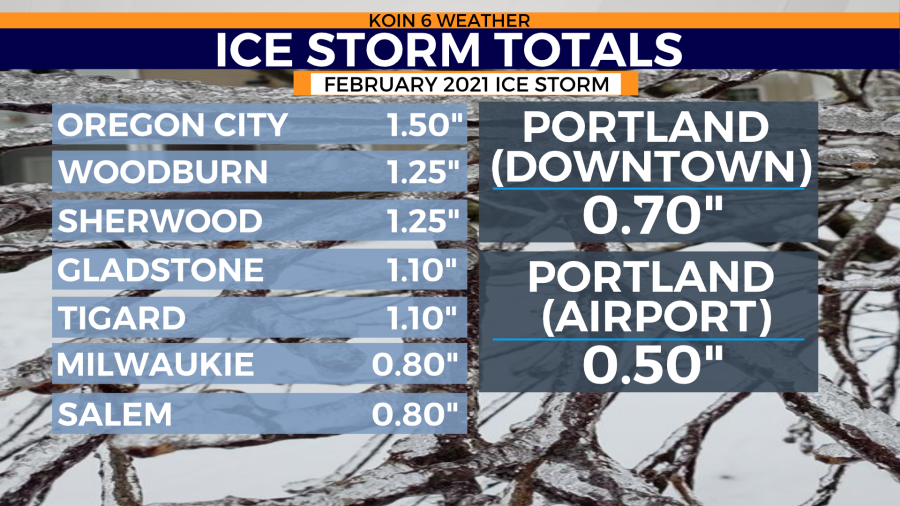

The final system that brought in rain, wasn’t overly impressive, but the ground was freezing. The air was eventually warm enough through the profile of the atmosphere from Portland south, but the ground was still frozen from the previous blast of cold air and snow. As rain moved in over the top of the frozen surface, the ice started to build. The rest is scratched into Oregon history. Ice storm totals ranged from minor (glaze) to major (1.50″) in Oregon City.

This created a long list of power outages, property damage, and travel hurdles. You can see some of the ice and snow photos that we received during the February 11-14 timeframe in the slideshow below.

RARE OR COULD THIS HAPPEN AGAIN?

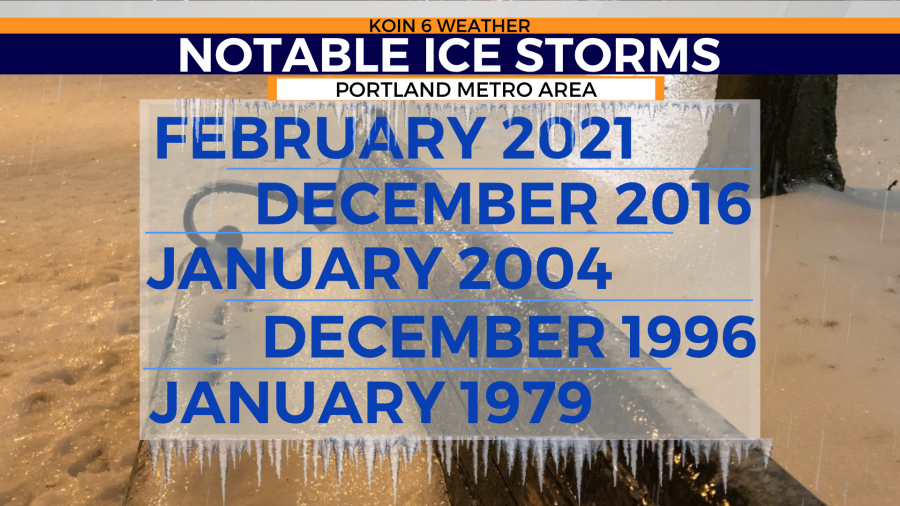

Was this event rare? Although not frequent, it isn’t rare. However, the February 2021 ice storm was one of the most demanding ice storm to impact the Willamette Valley. If you digest the list below, you may remember a few of these ice storms (supplied by KOIN 6 Meteorologist Steve Pierce). January 2004 was the last significant ice storm. December 2016 was not as major, but notable due power outages and timing.

Should we be prepared for more snow and ice events?

We should absolutely be prepared for more ice events and snow events. Although it is difficult to bring all the pieces together at once, it happens. We know the process, we the saw the outcome. It isn’t the first time that it has happened. Even with a warming climate, we have to take into the consideration that we have the secret weapon of the Gorge. The air will still be cold east of the mountains, especially with extremes. It may not be as frequent, but it will still be a possibility. We will always have the incoming rain from the Pacific Ocean too. We are almost set up for ice storms because of the clashing air masses that are frequently at the table each winter. The Gorge is at a heightened position for this type of winter weather, but the valley is shortly behind. A vicious ice storm closed down the Gorge in 2018. It happens, we are vulnerable to this type of weather.

THE FUTURE

A diagram of the Gorge effect is pictured in the graphic below. The Columbia Basin is known for cold winter temperatures. The climate is cold and dry in the winter. The channels that are built in between the Cascades, are the funnels that keep injecting the Willamette Valley with cold air. Sometimes this reaches the surface, other times it is a layer aloft that creates an icy scene due to sleet. This will not change unless the geography of the Pacific Northwest is altered. This should continue for the immediate future. How about long-term?

Paul Loikith, a climate scientist at Portland State University, has more about climate change and the projection of ice storms in the future:

“I don’t think that we need to worry much about climate change causing ice storms to get worse or more frequent in the Willamette valley or in Portland. They’ll continue to occur for quite a while. I do think that eventually winter warming will start to make these events become less frequent because you simply won’t have as often below freezing temperatures at the surface. So what would have been an ice storm will just become a cold rain storm, kind of that sort of thing.”