PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) – From year to year, the weather can aid to either a slow start to the fire season or it may offer the conditions for a robust jump to the season. When we approach the summer, the forecast starts to lean towards fire concerns.

Currently, we know that a lot of the spring has been dry for Oregon and Washington outside of our wet start to the month of June, leaving persisting drought conditions across both states. With the June gloom in place, we haven’t had to discuss a smoky sky or had to deal with air quality because of a wildfire.

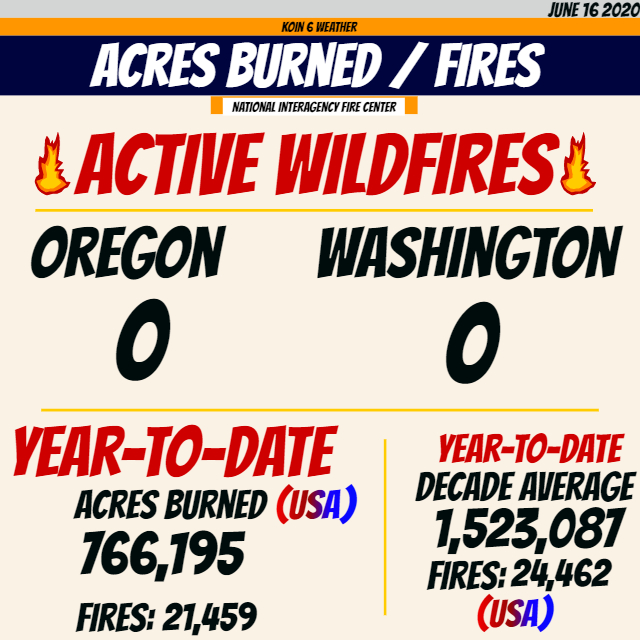

We’ve had one or two small fires that have caused a few issues locally, but the overall fire season hasn’t quite kicked into gear yet around the Pacific Northwest. As of June 16, we have no active wildfires in Oregon and Washington, according to the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) and the Northwest Interagency Coordination Center (NWCC). This doesn’t mean that we aren’t going to experience future troubles, but more so, we are currently fortunate.

Some interesting stats from the NIFC show our current acres burned across the United States at 766,195. If you compare that to the decade average as of June 16, we are below the average by a decent margin.

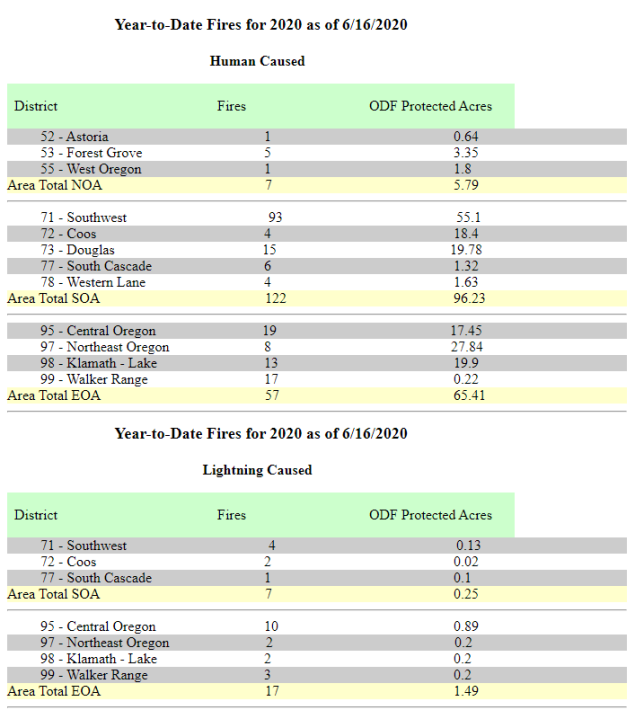

How about Oregon? According to the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF), we’ve experienced a handful of human and lightning-caused wildfires. There have been 210 total fires, a majority of those have been human-caused (186), coming to a total of 169.17 acres.

Lightning coming in at 1.74 acres of the 169.17, a small fraction. To see more ODF-provided data, some of which are below, you can find that here. You’ll notice that the areas around Northwest Oregon have not been impacted as hard as other sections of the state.

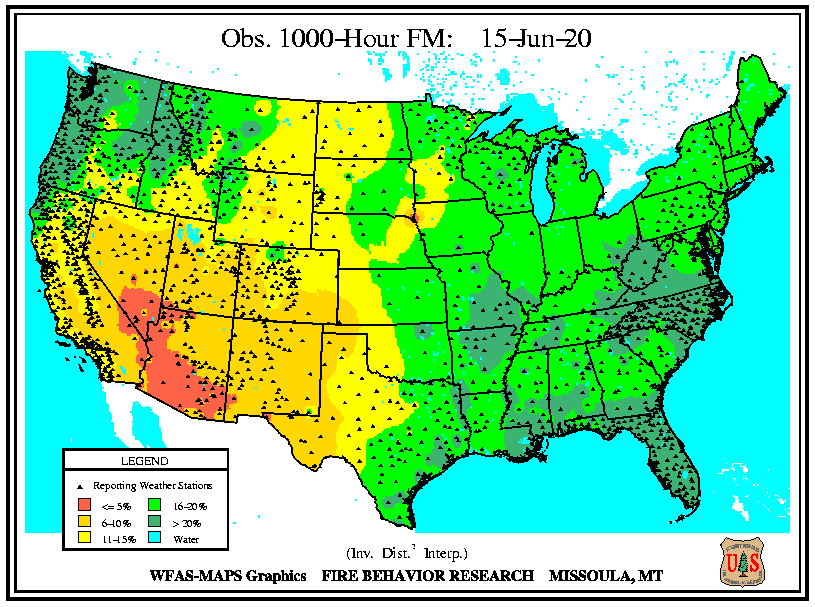

One aspect to keep in mind is the fuel moisture for fire behavior. Below is a graphic representing the 1,000-hour fuel moisture as of June 15. Fuel moisture is a measure of the amount of water in vegetation that you could say is available to a fire. When that moisture content is below 30%, it is considered to be dead fuel.

You can think of dead fuel as fallen logs, dead vegetation, or grasses that have dried up and are considered dead. Dead fuel is important to analyze because it responds directly to the conditions at hand, whereas vegetation that is living will respond differently.

Now the larger the dead fuel, the longer it may take to respond, for example, a dead log may take on moisture but it will take much longer for it to dry out compared to small grass blades. The 1,000-hour fuel moisture graphic will represent fuel size that is larger.

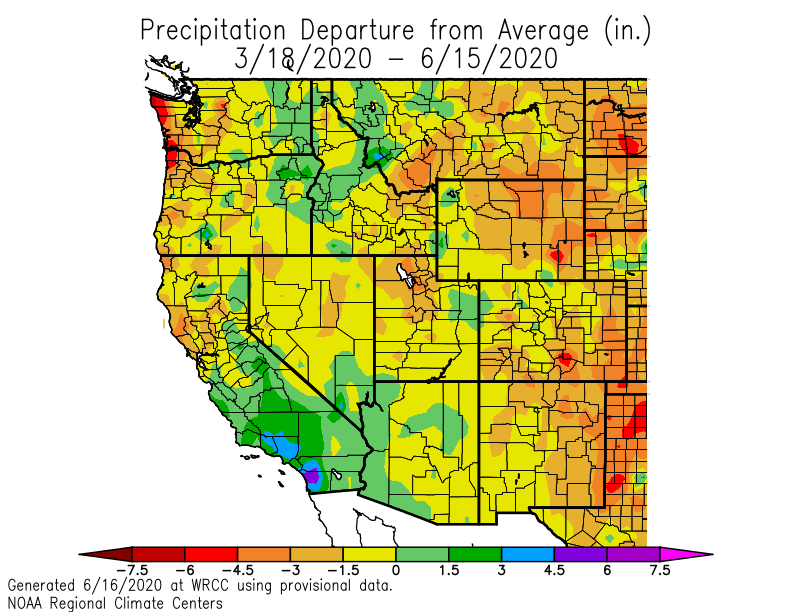

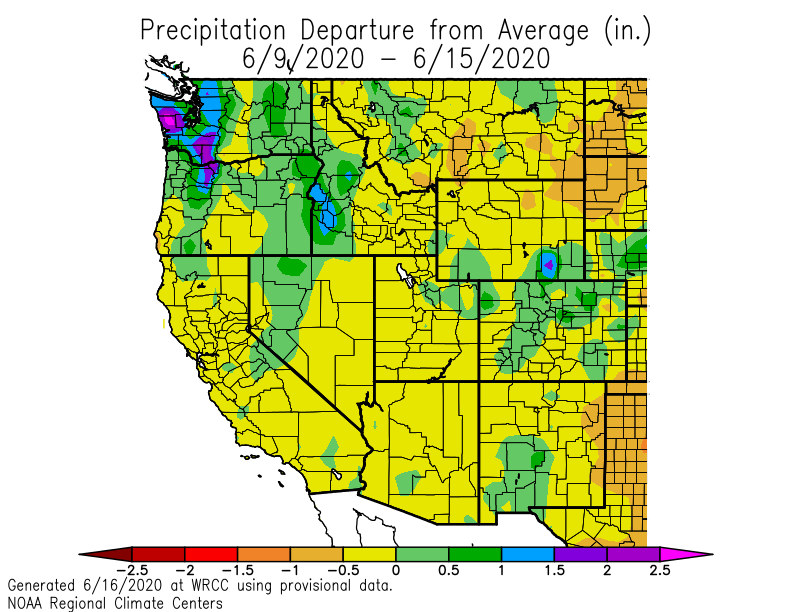

The next two graphics are dealing with precipitation departure, one that is 90 days and one that is seven days. The 90-day departure isn’t pretty. With that being said, we’ve already approached 3.00 inches of rain for the month of June, and the last week has been wet. Digest the positive numbers coming from the second graphic on the right.

Lastly, the forecast is calling for little moisture over the next six to 10 days. With a likelihood that we start a dry stretch for the PNW as we shift to a biting ridge of high pressure. This may alter our current conditions, but hopefully we have had enough moisture tucked away to help prevent any serious wildfires from forming. Of course, we can’t rule out additional lightning and human caused fires as we get closer to the Fourth of July.