PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Legislative leaders often say they don’t want to criminalize mental illness. But data reviewed by KOIN 6 News shows that is literally what they’re doing.

The bar is so high for involuntary civil commitment in Oregon — that is, forcing someone into treatment — just about the only way to get into the Oregon State Hospital is by getting caught for a crime.

The 3 pathways

It all comes down to unintended consequences.

Oregon law allows a person to be treated for a mental illness against their will if they are experiencing an emotional disturbance and are imminently dangerous to themselves or others.

The Oregon Court of Appeals has, in case law, narrowed what the terms “danger to self” and “danger to others” means, making it a very high bar to reach.

“When the doors to civil commitment closed, it was only a matter of time until the courts found a way in,” said Dr. Amit Bhavan, a psychiatrist at the Oregon State Hospital.

In 1993, the Oregon legislature passed laws outlining specific rights of people receiving mental health care. In the ‘least restrictive way’ they allowed the mentally ill the choice to participate as much as possible in all decisions that affect them.

The “least restrictive care” is something that comes from the U.S. Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision. Starting around 2007, the U.S. Department of Justice launched an inquiry examining whether Oregon was complying with Olmstead. The state has been grappling with that term ever since.

Multnomah County Circuit Court Judge Nan Waller presides over the criminal cases involving the mentally ill on a daily basis. She said the fact of giving the mentally ill a choice is “illusory.”

“That choice is really illusory when the involved individuals do not have access to robust continuum of local treatment, housing supports and social services,” Judge Waller said.

While the laws in Oregon were meant to reduce harm, Waller said that’s not what’s happening in real life. In order to keep the mentally ill out of the criminal justice system, she said Oregon needs an abundance of facilities for them to either be treated or live supervised in the community.

“Otherwise,” the judge said, “too often the only open door is the door into jail.”

The Oregon state hospitals are meant to treat the most severely mentally ill for a finite amount of time. Its current capacity is around 700 beds.

There are 3 pathways to enter, but all of them require a judge’s order:

>> Involuntary civil commitment, which required someone’s mental illness to have them in imminent danger of dying or physically hurting others. Only 2% of those in the state hospital were involuntarily committed.

>> Guilty except for insanity, meaning their mental illness is so bad they can’t comprehend the crime they committed. This accounts for about 40% of those in state hospitals.

>> Aid and Assist orders are when a judge determines a person accused of a crime is incapable of participating in their own defense. They are sent to the hospital to be restored enough to return to court. This path accounts for the remaining 58%.

Historically, these 3 categories used to be evenly divided. But psychiatrists say the Oregon State Hospital has seen a dramatic shift in its patient population the past few years.

Now, 98% of patients in the Oregon State Hospital are sent there by the criminal justice system — and some of them are there due to heinous crimes.

‘Criminalizing disability’

Advocates like Emily Cooper at Disability Rights Oregon don’t believe the bar needs to be lowered for civil commitments. They think there needs to be a wider array of community services for people who are actively asking for them.

“In Oregon we are criminalizing disability,” Cooper told KOIN 6 News. “The state hospital is being misused as a form of pre-trial detention based on stereotypes and discriminatory bias toward people with mental illness.”

State legislators asked experts how and why it’s gotten to this point. During a committee hearing, Rep. Lily Morgan, a Republican from Grants Pass, asked, “At what point is accountability through the legal system the only option when somebody has the right constitutionally to say, ‘I want no treatment,’ and in their illness are committing crimes and victimizing others?”

“One of the biggest issues that I’ve seen in my 25-year career is the change in what it takes to get someone civilly committed,” said Marion County DA Paige Clarkson. “If you aren’t able to get them services through a civil commitment process you’re going to end up getting them services through the criminal justice process.”

When the bar is so high to force the mentally ill into treatment, district attorneys argue people’s mental illness has to hit rock bottom in order to get involuntary intervention.

Washington County DA Kevin Barton said in many cases the standard for civil commitment is unreachable in Oregon.

“We see time and time again too few people meeting that standard,” Barton said. “We believe if more people could meet the standard we’d be able to divert people away from not just the criminal justice system but diverting people away from being in a position where a crime is ever committed, where a victim is harmed, where the police are called.”

Only 2% of patients at the state hospital are there because of civil commitment.

In recent months, a federal court order, the Mosman Decision, forced the state hospital to speed up the release of mentally ill patients to make room for the dozens of mentally ill inmates currently languishing in jail.

Former Oregon Health Authority Director Dr. Patrick Allen said the Mosman Decision has made the already slim chances of getting the mentally ill civilly committed practically impossible.

Records from the Oregon State Hospital reveal the few people who are civilly committed average about 18 months of treatment. Those who are there because they’re guilty except for insanity usually are treated for about 3.5 years.

But the 58% of patients at the state hospital on Aid and Assist orders average a short stay of 90 days with a limited goal of getting to “restored competency.” Basically, the 90 days is enough time to detox so they can at least recognize who they are and what the court system is.

“This crisis at the hospital was not caused by the Mosman decision, it was caused by the decision to use the criminal legal system to address the issues and concerns around mental illness,” said public defender Grant Hartley. “The criminal justice system is not only ineffective in treating mental illness, it is counter-productive.”

Public defenders say this routine at the state hospital often gets the mentally ill well enough to get convicted of a crime to serve a limited sentence in jail– only to return to the streets less stable than before.

“It can’t be said enough: This is a systemic issue across public safety and mental health systems,” said Eva Rippeteau with AFSCME.

Meanwhile, the Oregon State Hospital recently reported a nearly 25% increase in the number of Aid and Assist orders from judges to treat mentally ill people wrapped up in the criminal justice system.

Reoffending, recidivism

State hospital nurses and psychiatrists said this lack of comprehensive mental health treatment for the majority of their patients leads to a high risk of reoffending and recidivism in both the criminal justice system and the state hospital.

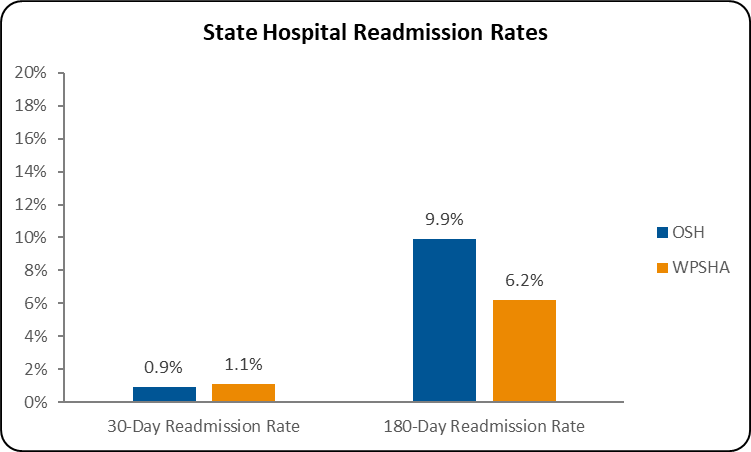

Psychiatric hospitals in the US track repeat patients by 2 measurements: those who get readmitted after 30 days and those readmitted after 180 days.

The Oregon State Hospital said patients who get sent back to a state hospital within 30 days can signal there was an issue or failure with treatment. But patients readmitted after 180 days can signify there’s a failure within the community to treat this patient’s chronic mental health issue.

Data shows the Oregon State Hospital does a better job of treating patients up front compared to other psychiatric hospitals in the West, leading to a low 30-day readmission rate.

But the state hospital falls behind its Western counterparts in the 180-day readmissions, indicating Oregon needs more services to support a successful return into the community. Overall, in the latest annual report, Oregon State Hospital received 921 repeat patients.

Over and over, leaders in Oregon repeatedly testified to lawmakers changes must be made.

“The system is failing. I think that needs to be recognized,” Barton said.

“This system is broken,” said Lane County Commissioner Pat Farr. “We need a system that gets real treatment for people, not just treatment to fulfill their obligation to the court.”

But fixing it is a collective challenge.

In Lane County, where the Junction City State Hospital is located, commissioners said it will require a true partnership of the legislature to develop legal guidelines to give mental health professionals on mobile crisis teams a place to take people in crisis.

Current capacity at the Oregon State Hospital is slightly lower than it was 20 years ago, leading some at the OHA to think there should be more beds. Psychiatrists estimate they need an additional 700 workers at the state hospital.

Multnomah County Mental Health Interim Director Julie Dodge explained that some severely mentally ill patients will require supervised lifetime care in secure assisted living facilities outside of the Oregon State Hospital.

“If we can make an impact here with the most vulnerable 2-3% we will significantly reduce our costs across our whole system,” Dodge said.

Experts and advocates at every level are calling for more stepdown services from the Oregon State Hospital to help keep the mentally ill and community safe.

“The state hospital, just like an emergency department, is not long term care,” said Disability Rights Oregon’s Cooper.

What is needed

Oregon needs more of everything, advocates said, including inpatient and outpatient facilities, dual diagnosis programs treating addiction and mental illness, along with meaningful long-term supportive housing and community-based behavioral health services for people with severe and persistent mental illness.

Teri Anderson, who advocated on behalf of her son Joshua who died of a drug overdose at 28 years old in a doorway of a shelter in downtown Portland, said she was only able to see his medical records after he died.

“When I got his paperwork after he died, all through it they’re saying he’s psychotic, he’s delusional, he believes his girlfriend’s head was taken off by a terrorist organization and OHSU put it back on,” Anderson told KOIN 6 News. “That doesn’t scream to me, ‘I can make my own decisions.'”

Had she been able to gain guardianship and get access to these records, she believes it would’ve helped her get him civilly committed into treatment — and that he’d still be alive today.

State leaders are working toward solutions.

In 2020 and 2021, they passed several bills allocating a little more than $1 billion toward addressing the current problems. Three prominent investments aim to address major shortfalls:

>> They invested $130 million to add beds and supportive housing facilities for people with serious and persistent mental illness. So far it’s added more than 300 beds, with more beds by the end of the year. Still, these are major projects and none are fast.

>> Lawmakers put $100 million of one-time funding into community mental health programs for adult foster homes, secure residential treatment facilities, substance use disorder units and many other necessary behavioral health treatment centers.

>> Lawmakers invested more than $120 million in federal and state dollars to provide incentives to increase salaries for mental health workers to help with recruitment and retention of professionals to this field.

Most of that money — 85% — is finally out the door. The fruits of that spending will become apparent later this year and in 2024. But public health leaders said it is not sufficient by itself.

Rep. Rob Nosse, who chairs the Behavioral Health Committee, told KOIN 6 News the legislature is not ready to make civil commitments easier mostly because they don’t have the facilities to send people to — yet. But Nosse said to stay tuned as the investments begin to show results.

He does think there will be more bills to try and make it a little easier to force someone into treatment.

The Oregon Judicial Department initiated an 18-month multi-stakeholder workgroup, “Commitment to Change,” that is undertaking a comprehensive review of Oregon’s civil commitment laws and processes.

The Chief Justice appointed members to the workgroup representing more than 20 stakeholder groups, including legislators, judges, state agency staff, counties, cities, law enforcement, prosecutors, defense lawyers, Oregon State Hospital and community-based behavioral health providers, and disability rights advocates.

The voices of people with lived experience are incorporated in the workgroup’s membership and through monthly surveys that are distributed to all interested persons (contact Christopher.J.Hamilton@ojd.state.or.us to offer comments or be added to the distribution list).

The Chief Justice will consider the workgroup’s recommendations for a proposal to the legislature in the 2025 session.